In medicine – heck, in just anything – we like to give ourselves credit. If it’s a horse, we see, or think we see, that something is wrong with a horse, and we want to do something (honestly, that’s pretty much exactly what I wrote on my application to veterinary school). We want to help. And we usually do do something, Sometimes – many times – the horse gets better (or we think it gets better). What could be more natural than to give the “something” credit for the improvement, and give ourselves a big pat on the back for our good efforts and good intentions? It feels great to feel like you’ve helped.

In medicine – heck, in just anything – we like to give ourselves credit. If it’s a horse, we see, or think we see, that something is wrong with a horse, and we want to do something (honestly, that’s pretty much exactly what I wrote on my application to veterinary school). We want to help. And we usually do do something, Sometimes – many times – the horse gets better (or we think it gets better). What could be more natural than to give the “something” credit for the improvement, and give ourselves a big pat on the back for our good efforts and good intentions? It feels great to feel like you’ve helped.

Unfortunately, on that simple line of thinking, pretty much every single treatment can be said to be successful, at least sometimes. And therein lies the biggest fallacy in medicine. That being, “Because I did this, the result I was hoping for happened.”

So why is this unfortunate? Well, mostly because it’s not necessarily true. That is, just because one thing follows another doesn’t mean that the first thing has anything to do with the second. Just because two things are related to each other in time doesn’t mean that the first thing caused the second thing.

So why is this unfortunate? Well, mostly because it’s not necessarily true. That is, just because one thing follows another doesn’t mean that the first thing has anything to do with the second. Just because two things are related to each other in time doesn’t mean that the first thing caused the second thing.

The problem is that if you think like this (and it’s not an irrational way to think, by the way), you’re going to end up buying into a lot of different products, services, or treatments. You’re going to go down into a lot of therapeutic blind alleys and dead end streets. You’re going to waste time and money. And none of it will help your horse (even though you may be quite convinced that it did).

BRIEF ASIDE: I absolutely love it when people comment on articles that I post. I encourage people to post their differing experiences, too, because I love to learn from everyone. But it absolutely baffles me how the occasional person will come on the site and flame me for allegedly not knowing what I’m talking about because their horse got better after this or that was done, when I’ve pointed out that there’s actually very little evidence for the effectiveness of whatever was done. The fact that there’s not evidence for a particular procedure or treatment isn’t personal, but some folks sure want to seem to make it so!

This line of thinking – the biggest fallacy in medicine – is so common, that’s it’s even got a formal name, in Latin. It’s a logical fallacy called post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this). Now, as far as I know, the saying can’t be attribute to anyone in particular, and, apparently, Latin was such a frustrating language that nobody speaks it any more. But it’s still true. And the fallacy is the basis for many erroneous beliefs about all sorts of things: not just medicine.

This line of thinking – the biggest fallacy in medicine – is so common, that’s it’s even got a formal name, in Latin. It’s a logical fallacy called post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this). Now, as far as I know, the saying can’t be attribute to anyone in particular, and, apparently, Latin was such a frustrating language that nobody speaks it any more. But it’s still true. And the fallacy is the basis for many erroneous beliefs about all sorts of things: not just medicine.

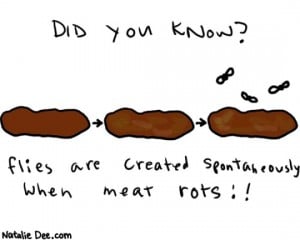

Ever hear of “spontaneous generation?” It was the way of the world throughout much of human history. The idea was that ordinary living things could arise without having descended from other ordinary living things. Take maggots (please). For much of human history, it was thought that maggots arose from decaying things, like rotting meat. And, when you think about it, it’s not really such a dumb idea. I mean, if you put out some meat to rot (or, as was likely the case in the Middle Ages, you’ve got bodies or carcasses lying around), pretty soon you’re going to have a bunch of maggots. And it’s certainly not obvious where they come from – fly eggs aren’t nearly as obvious as, say, ostrich eggs. So, it was commonly thought – by some really smart people, including Aristotle, the famous Greek doctor/philosopher/scientist/bon vivant – that the maggots just arose from the meat. One thing followed another.

And it was that was for literally thousands of years. But an enterprising Italian scientist, Francesco Redi, performed an experiment in 1688, where he placed meat in a variety of sealed, open, and partially covered containers. When the containers were open: maggots. When they were covered: nothing. Got people thinking, and, in a reasonable period of time (nearly 200 years, actually, which is another thing to think about when you start wondering why stupid therapies stick around in spite of their ineffectiveness), the idea of “spontaneous generation” was put to rest. By the way, if you want to read more about all of this CLICK HERE.

When you start thinking about this fallacy, you can come up with all sorts of examples. How about the rain dances allegedly performed by the natives of the American Plains? They danced: sometimes it rained. So, apparently, they kept dancing. The railroad crossing alarm sounds, the gates come down, and a train passes. Why? The railroad crossing causes the train to pass, of course. You put in a new bit of software and your computer crashes: has to be the software’s fault, right?

When you start thinking about this fallacy, you can come up with all sorts of examples. How about the rain dances allegedly performed by the natives of the American Plains? They danced: sometimes it rained. So, apparently, they kept dancing. The railroad crossing alarm sounds, the gates come down, and a train passes. Why? The railroad crossing causes the train to pass, of course. You put in a new bit of software and your computer crashes: has to be the software’s fault, right?

Often, it’s all for the birds.

And speaking of birds, did you know that people used to believe that geese grew on trees? Check this out.

Of course, it’s not like pointing out this fallacy is anything new. For example, here’s a quote from 1938, from the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association. “Think what a number of drugs that for years had an honoured place in the pharmacopaeias have have fallen by the way. All used with apparent success and then found to be inert, the good results having been having been sequences to other factors than the drugs. They have gone the way of human urine, feces, mice, toads, the washings of the tombstones from the saints, etc., all of which had their day” (CLICK HERE if you want to see the whole article).

Of course, chasing this fallacy happens all the time in horse medicine, too. The examples – even in my career of just over three decades – are almost too numerous to list (it would be a REALLY long list). And new examples keep cropping up all the time.

Still, even though we’ve known about this fallacy for a long, long time, it seems to have a hard time making an impression on some folks. In fact, the post hoc fallacy appears to have some very impassioned defenders. Take colic. I have had the temerity to note that walking a horse may not really be that important when it comes to treating a horse for colic – I then get some pretty adamant responses that it sure worked for someone’s horse (along with comments along the lines of, “How could you say such a thing?!!”) Or, I’ve noted that flunixin (Banamine®) is not a potent pain reliever, and, emboldened by the surety that comes from having had a horse stop showing pain after a flunixin injection, there’s no way that the medical research (or me) can be correct.

Now, of course, I’m not saying that because events are connected in time doesn’t mean that there can’t be a relationship. Of course there can. But that’s where science and evidence comes in. It’s a way to try to help us determine if the relationships that we regularly notice in time – one thing after another – really have anything to do with each other. Because if they do, then great, we might be onto something. But if they don’t, well, we can all stop wasting our collective time (and money).

So what do I think that you should do with this bit of information? Well, for one, how about be humble? Believe me, I know how good it feels to have a horse get better after you’ve done something – it’s been the goal of my entire career. But sometimes we give ourselves too much credit. The post hoc fallacy is a trap that everyone can fall into. Don’t be too ready to believe what you see, and don’t be too quick to criticize those that may not be seeing the same thing.

ASIDE: One of my favorite quotes is, “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a hard battle” (a quote that is commonly attributed to Plato, but actually is from the Scottish author and theologian Dr. John Watson, whose pseudonym was Ian Maclaren, and who you can read about if you CLICK HERE).

And for goodness sakes, don’t go about jumping on every diagnostic or therapeutic bandwagon that comes along, just because it’s accompanied by an earnest testimonial. There’s at least a pretty good chance that the post hoc fallacy is at play.