“Mares… had not been altered, in them the blood flowed freely, their life cycles had not been tampered with, their natures were completely their own. The mares usually had more energy than the geldings, could be as temperamental as the stallion and was, in fact, its superior.” John Hawkes – Whistlejacket

Personally, I think mares tend to get a bum rap.

DISCLAIMER: My horse is a 5 year old Warmblood mare.

There have been lots of great mares. At almost 17 hands tall and jet black, Ruffian is considered by just about everyone to have been one of the greatest racehorses of any gender that has ever lived. Ruffian made a total of 11 lifetime starts, winning all but her final, and ultimately fatal, match race against 1975 Kentucky Derby winner Foolish Pleasure. I remember that horrible day. I was rooting for her.

Touch of Class, a bay Thoroughbred mare, was only 16 hands tall, yet she posted the first double clear rounds in Olympic show jumping history. She took home two Gold Medals from the 1984 Olympics (where it was rumored that the oxers were larger then her stall). The little mare could really jump! She’s a legend in the show jumping world.

And, of course, the word “great” can be used in many contexts. Sarah was a Quarterhorse mare who has happily carried her owner over fences, across creeks, through deserts, and around traffic for 20 years (depending on where she was stabled). Over the years, she won ribbons: and hearts. Sarah’s was pretty great by any definition, although she never got any publicity (until now). She had to be put to sleep a few years ago at the ripe old age of 33. All goof things must end.

Lisa Simpson has a pony – her name is Princess.

Of course, there’s also the old grey mare, but she ain’t what she used to be.

So, given that there are, and have been, so many great mares, why is it that so many people seem to be reluctant to keep them? In my opinion, it mostly boils down to one thing – mares come into heat.

Like most mammalian species, mares are looking to keep their species alive. When mares are in heat, they can be pretty obvious about it, because they are looking to get bred. In fact, some mares, when in heat, do give some rather obvious – and to their owner’s: embarrassing – displays of the fact that they are in heat. And other horses may notice, too!

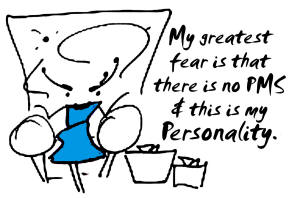

It’s a fact that women get accused of being moody during their reproductive cycles, too. Almost stereotypically so. For example, a woman  who is having emotional swings may be said – in something of a knee-jerk reaction – to have PMS (and much worse). It’s pretty much set in peoples’ minds that reproductive cycle changes = mood and behavioral changes. Since people have set in their mind that human females have emotional swings as a result of their reproductive cycles, when people grumble and generalize about moodiness and behavioral changes and erratic performance of female horses they always have the explanation for it: “She must be in heat!” While sometimes there may be an influence of reproductive hormones, the fact is that many times a mare’s poor behavior or performance has nothing to do with her reproductive cycle at all. Horse moods, like people moods, can vary from day to day.

who is having emotional swings may be said – in something of a knee-jerk reaction – to have PMS (and much worse). It’s pretty much set in peoples’ minds that reproductive cycle changes = mood and behavioral changes. Since people have set in their mind that human females have emotional swings as a result of their reproductive cycles, when people grumble and generalize about moodiness and behavioral changes and erratic performance of female horses they always have the explanation for it: “She must be in heat!” While sometimes there may be an influence of reproductive hormones, the fact is that many times a mare’s poor behavior or performance has nothing to do with her reproductive cycle at all. Horse moods, like people moods, can vary from day to day.

He that speaks ill of the mare will buy her – Benjamin Franklin

Still, because mares do come into heat, and because – rightly or wrongly – their behavior on any particular day tends to get associated with their reproductive cycle, trying to keep mares from coming into heat has turned into something of an obsession, particularly for owners of performance horses. Folks try to keep mares from coming into heat in any number of ways, some of which work, and many of which don’t (but still get used). It’s a closet industry, of sorts.

Before you can try to control the mare’s heat (estrous) cycle, you sort of have to understand the mare’s heat cycles, so let’s briefly talk about it. The normal mare’s cycle is 21 – 22 days long. It’s made up of two parts – diestrus, the approximately 15 day period when the mare isn’t showing signs of heat, and estrus (heat), the 5 – 7 day period that some horse owner’s apparently fear. There’s also a period of time every year where mare’s don’t come into heat – for several months a year, starting in the late fall in most places, the mare’s reproductive cycle just stops. The teleological* explanation is that by not being able to breed when it’s cold outside, it prevents that mare from giving birth when the weather conditions are at their worst and food is least available: times when, presumably, if a foal was born, it would have a very hard time. The fact that mares are in heat only during a certain time of the year is also why a lot of effort has been devoted to getting mares to start their reproductive cycle when they’re not really supposed do be having a reproductive cycles (see, for example, Thoroughbred racing, where for racing purposes, all horses have a birthday on January 1st, and breeding barns can be lit up like Times Square at night in late November).

Before you can try to control the mare’s heat (estrous) cycle, you sort of have to understand the mare’s heat cycles, so let’s briefly talk about it. The normal mare’s cycle is 21 – 22 days long. It’s made up of two parts – diestrus, the approximately 15 day period when the mare isn’t showing signs of heat, and estrus (heat), the 5 – 7 day period that some horse owner’s apparently fear. There’s also a period of time every year where mare’s don’t come into heat – for several months a year, starting in the late fall in most places, the mare’s reproductive cycle just stops. The teleological* explanation is that by not being able to breed when it’s cold outside, it prevents that mare from giving birth when the weather conditions are at their worst and food is least available: times when, presumably, if a foal was born, it would have a very hard time. The fact that mares are in heat only during a certain time of the year is also why a lot of effort has been devoted to getting mares to start their reproductive cycle when they’re not really supposed do be having a reproductive cycles (see, for example, Thoroughbred racing, where for racing purposes, all horses have a birthday on January 1st, and breeding barns can be lit up like Times Square at night in late November).

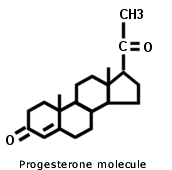

The mare’s cycle is influenced by various hormones. Hormones are regulatory substances; they are usually produced in one spot, and then transported in tissue fluids (such as blood) to a target tissue, where they stimulate specific cells or tissues into action. When the mare is in diestrus – when she doesn’t show signs of heat – the hormone that has the most influence is called progesterone. When there’s lots of progesterone in the mare’s bloodstream, the mare’s not in heat. And that’s the point of most of the therapies that are out there – they try to increase the level of progesterone, in one way, or another.

The mare’s cycle is influenced by various hormones. Hormones are regulatory substances; they are usually produced in one spot, and then transported in tissue fluids (such as blood) to a target tissue, where they stimulate specific cells or tissues into action. When the mare is in diestrus – when she doesn’t show signs of heat – the hormone that has the most influence is called progesterone. When there’s lots of progesterone in the mare’s bloodstream, the mare’s not in heat. And that’s the point of most of the therapies that are out there – they try to increase the level of progesterone, in one way, or another.

Mares are (mostly) great. Many mares work and perform just fine no matter what stage of the heat cycle they are in. However, if you’re worried about a mare’s heat cycle, and you want to try to control it, it seems to me that you should use something that actually works. Part 2 is going to talk about many of the different treatments that people use to try to keep their mare’s heat cycle under control.

* For those of you that aren’t also word geeks, teleology is is a reason or explanation for something based on that something’s supposed purpose or goal.