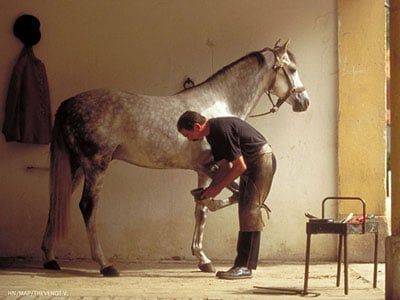

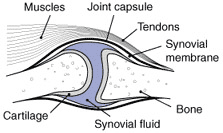

The framework of your horse’s body is the skeletal system, made up of bones. Anywhere two bones meet, you’ll find a joint. In joints that move, such as the joints of the lower limbs, the ends of the bones joint are covered with a thin, white covering called cartilage. Cartilage is a smooth and resilient tissue that allows the ends of the bone to move with virtually no friction, and that also allows the forces placed on the joint to be spread uniformly across it. Cartilage is also very well hydrated, which helps to cushion the forces applied to the joint, in the same sort of fashion as a waterbed.

The framework of your horse’s body is the skeletal system, made up of bones. Anywhere two bones meet, you’ll find a joint. In joints that move, such as the joints of the lower limbs, the ends of the bones joint are covered with a thin, white covering called cartilage. Cartilage is a smooth and resilient tissue that allows the ends of the bone to move with virtually no friction, and that also allows the forces placed on the joint to be spread uniformly across it. Cartilage is also very well hydrated, which helps to cushion the forces applied to the joint, in the same sort of fashion as a waterbed.

Surrounding the joint is a fibrous joint capsule. The fibrous joint capsule is the wrapping paper of the package that is the joint. Lining the joint capsule is a thin membrane, richly supplied with blood vessels, called the synovial membrane. The synovial membrane is a critically important structure, as it produces the synovial (joint) fluid that’s normally in joints, as well as the numerous inflammatory compounds that are present in diseased joints.

Synovial fluid is vital for joint health. This fluid has a number of functions, including lubricating the joint and the tissues that envelope it. But that’s not all that synovial fluid does. Synovial fluid also provides nutrition to the cartilage cells. Since normal cartilage has no blood vessels, lymph vessels, or nerves, anything that’s put into a joint – or into the horse – has to diffuse into the cartilage from the joint fluid to be able to have any effect on the cartilage. This means that anything that is put into the horse, or its joints, has to be in sufficient concentration, and stay for sufficient time, to be able to have any effect.

Synovial fluid is vital for joint health. This fluid has a number of functions, including lubricating the joint and the tissues that envelope it. But that’s not all that synovial fluid does. Synovial fluid also provides nutrition to the cartilage cells. Since normal cartilage has no blood vessels, lymph vessels, or nerves, anything that’s put into a joint – or into the horse – has to diffuse into the cartilage from the joint fluid to be able to have any effect on the cartilage. This means that anything that is put into the horse, or its joints, has to be in sufficient concentration, and stay for sufficient time, to be able to have any effect.

Since nutrients have to diffuse into cartilage, it can’t be very thick, or nutrients wouldn’t be able to get to all of the cartilage cells (otherwise stated, if cartilage were thick, nutrients would be unlikely to get to the deeper layers, just like cold temperature can’t get to your hands when you’re wearing a

Chance

thick pair of gloves). Furthermore – and this is a big problem for athletic horses – cartilage has only very limited ability to repair itself. Since cartilage is isolated from the body’s blood supply, it doesn’t have a very active metabolism (compared to, say, the skin). That means that cartilage cells don’t replace heal well when they are damaged. Instead, cartilage damage usually results in permanent damage to a joint, at least eventually. All of this means that a little damage to the cartilage can cause big problems.