Not me

I have been working on horse teeth for over 3 decades. I have to say, it’s been an interesting journey. Not as much from the actual business of working inside a horse’s mouth – in most cases, that’s pretty straight-forward – but more from having to “learn” how wrong everything that I had been doing currently done was wrong, well, pretty much all the time.

ASIDE: Curiously, that “learning” generally comes from other folks that want to do the job that I’m doing… think it’s a coincidence?

Also not me

Anyway, I had a call from a prospective client not long ago. She asked me if I could vaccinate her horses. I told her I could. She asked me if I could check her horses for parasites. I told her I could. She asked me if I could take a look inside her horses’ mouths and do any dental work that was needed. I told her I could. She asked if I used power tools. I told her I did. She told me that I was doing it all wrong, that I was damaging horses’ teeth, thanked me, and hung up.

Which got me thinking….

I actually remember the first time that I worked inside a horse’s mouth (I had observed dental work before working with veterinarians prior to veterinary school, of course). I was a junior in veterinary school. I worked with a senior student under the tutelage of one of my professors (Dr. Dwight Bennett, a real legend at Colorado State University). This was prior to all of the stuff that passes for knowledge that we have now. We naively examined the mouth, grabbed the horse’s tongue (to keep from lacerating it and to help keep us from getting bitten), grabbed our dental tools, filed away some sharp points, and basked in the confidence and sense of accomplishment that is gained when one learns something and gets accolades for it at the same time.

Not me, either

Thus, educated (having also worked on other horses in the interim) I entered veterinary practice armed with dental tools and confidence. I did a few sets of teeth during my internship at Iowa State University, and went right on addressing dental problems when I moved to California. I’d sedate the horses, grab their tongues, work away on the sharp, pointy spots that I could find, and all was good. Horses did great, clients were happy, birds sang… I mean, what else could you want, dentistry-wise?

For a time.

To my dismay, I soon found out that I didn’t know what I was doing. In fact, I found out that I didn’t have any interest in what I was interested in doing, either. I found this out because other people were going about telling horse owners that veterinarians didn’t know anything about the horse’s mouths and didn’t have any interest in them. Or, that “specialists” were always needed. I found those assertions a bit curious, especially since I was regularly being asked to work inside horses’ mouths and I actually found it kind of interesting. So I didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to those other people.

But they persisted.

Curious about all of the hubbub building around an area of the horse about which I had paid some attention but never really thought of as a huge deal, I decided to attend a seminar on equine dentistry. There, I worked with  some very earnest and informed colleagues who helped me refine my techniques. I was especially impressed with the speculems used to open up the horse’s mouth; you could really get a close look inside the mouth and, best of all, no more tongue-grabbing! I promptly bought one: still use it today. Armed with my new knowledge, and my new speculem, I confidently went about taking care of horse teeth, albeit with a slight tinge of regret at not having had a speculem to lug around. After all, I’m sure that I had not been addressing all of the horse’s teeth previously (even though the horses all seemed to do just fine). Plus, my new tool made me feel like I had moved onto the cutting edge. So, even though I allegedly still didn’t know what I was doing and allegedly still wasn’t interested, I went on, brimming with self-confidence, now leveling and smoothing and doing such work inside the mouth as I thought was needed with the benefit of knowing I was now up-to-date. And the horses did well.

some very earnest and informed colleagues who helped me refine my techniques. I was especially impressed with the speculems used to open up the horse’s mouth; you could really get a close look inside the mouth and, best of all, no more tongue-grabbing! I promptly bought one: still use it today. Armed with my new knowledge, and my new speculem, I confidently went about taking care of horse teeth, albeit with a slight tinge of regret at not having had a speculem to lug around. After all, I’m sure that I had not been addressing all of the horse’s teeth previously (even though the horses all seemed to do just fine). Plus, my new tool made me feel like I had moved onto the cutting edge. So, even though I allegedly still didn’t know what I was doing and allegedly still wasn’t interested, I went on, brimming with self-confidence, now leveling and smoothing and doing such work inside the mouth as I thought was needed with the benefit of knowing I was now up-to-date. And the horses did well.

For a time.

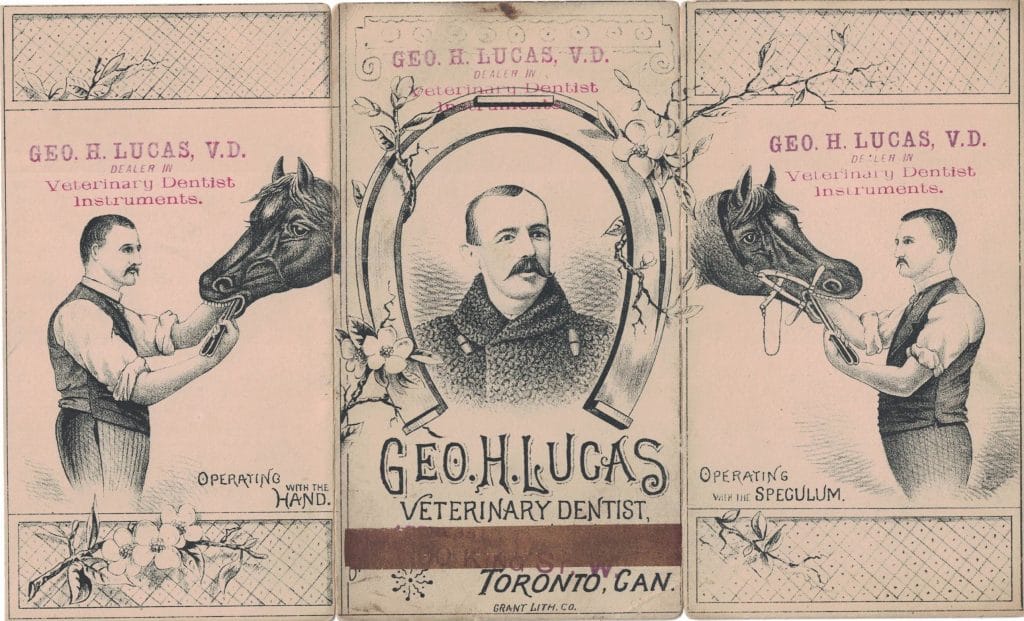

WWI Horse Dentist, France

Suddenly, my tools were a problem. Even though people had been grinding away with hand tools for a couple of centuries, I now didn’t have the latest equipment. Entrepreneurs had now come up with power tools to make grinding on horse teeth even easier. Now, teeth could be addressed with electrically powered grinders! If you didn’t have one of those, you were almost certainly behind the times. Without a power tool, how could you effectively and efficiently address all of the little points, waves, and hooks inside the next unsuspecting horse’s mouth? I was curious.

So I looked deeper.

While working on horse teeth with hand tools was a bit of a drudge, I liked the idea of using power tools because I also liked the idea of keeping my shoulders in good health. Following working on half-a-dozen sets of horse teeth by hand, I’d find that my shoulders would get tired and I was unable to grip or hold anything (like a cup of water) due to the muscle fatigue induced by clasping the handles of my dental floats. Aware that technological advances had made such things as turning screws, sawing wood, or driving nails a good bit easier, I was persuaded that a technology upgrade tooth-wise might not only be useful, but add to my longevity as an equine practitioner, as well. So I bought one. Even though I allegedly still didn’t know what I was doing and allegedly still wasn’t interested, I went on, brimming with self-confidence, now leveling and smoothing and doing such work inside the mouth as I thought was needed with the benefit of knowing I was now up-to-date. And the horses did well.

For a time.

For a time.

Turns out that, some folks, including, apparently, my might-have-been client, have recently learned that my new (now old) power tools – the ones that not having was a problem previously – are, in fact, a big problem if you have them now. It seems that there’s the possibility of thermal damage to the tooth when one uses power dental equipment. In fact, they’ve even done studies showing that the interior of the tooth can heat up to the point that it can damage the vital (living) structures of the tooth. Plus, the longer you grind on a tooth, the hotter it can get. So, if you sit and hold a power dental tool on a tooth for 90 seconds, the inside of the tooth can get REALLY hot. You can really do some damage! Especially if you’re intent on acting stupidly.

WAIT A SECOND… Did you know that you can break a screw with a power screwdriver? Did you know that while food is a good thing, too much food can make you fat? Did you know that if drive the very best designed and constructed automobile into a wall very fast you can hurt yourself (not to mention the wall)?

WAIT A SECOND… Did you know that you can break a screw with a power screwdriver? Did you know that while food is a good thing, too much food can make you fat? Did you know that if drive the very best designed and constructed automobile into a wall very fast you can hurt yourself (not to mention the wall)?

I bring this up because there seems to also be something of a disparity between the possibility of power dental tools causing thermal damage to the tooth and actual reports of power dental tools causing damage to the tooth. Something of a disparity as in, there aren’t any reports of power dental tools causing damage to the tooth. In fact, as noted in a 2017 review article by Dr. Rob Pascoe a veterinarian specializing in equine dental care in the UK, “The research clearly indicates that there is a likelihood of uncooled motorised instruments causing significant heating of dental tissues during their use. The consequences of this heating remain unestablished in the clinical situation, although it is clear that temperature increases to levels likely to cause direct thermal trauma to the pulp in other species are possible with inappropriate use (NOTE: I added the italics). Finally, using water cooled instruments can eliminate temperature increases.”

Here are a few takeaways from all of this:

- The British spell words like “motorised” differently than in the US. We are two countries separated by a common language (quote attributed to George Barnard Shaw).

Many power dental tools are now water-cooled. So, even if someone were intent on overheating a horse’s tooth, it would be even harder with a water-cooled instrument.

Many power dental tools are now water-cooled. So, even if someone were intent on overheating a horse’s tooth, it would be even harder with a water-cooled instrument.- You can just as easily damage a horse’s mouth with hand tools as you can with power tools. You can easily cut and bruise a horse’s mouth with hand tools is you’re not careful.

- Being careful is a good idea when it comes to grinding on horse teeth, no matter what tools you use.

- You shouldn’t be grinding away at a horse’s mouth willy-nilly anyway.

- Everything old is new again. Apparently, hand tools were the thing, then they were out-dated, and now they’re the rage once more (in some circles).

- When someone sells a procedure based on a criticism of another (as opposed to on its own merits) you have reason to be suspicious of that someone’s motives.

The problem, when it comes to horse dentistry – as with so many things – is that it’s not necessarily the tool, it’s the operator. If you’re worried about your horse’s mouth because of the incessant bleating about how the teeth have to be constantly managed, have a good oral exam done. Have it done by someone who is willing to tell you that your horse’s mouth is OK, too. There’s not likely to be much harm in that. There’s also unlikely to be much harm from the occasional, as needed, conservative intervention in the horse’s mouth, power tool or otherwise. However, if someone’s intent on “correcting” your horse’s mouth be a little wary, no matter what kind of tools used. And – these are words to live by – if you’re going to use a tool – ANY tool – don’t be stupid about it.

The problem, when it comes to horse dentistry – as with so many things – is that it’s not necessarily the tool, it’s the operator. If you’re worried about your horse’s mouth because of the incessant bleating about how the teeth have to be constantly managed, have a good oral exam done. Have it done by someone who is willing to tell you that your horse’s mouth is OK, too. There’s not likely to be much harm in that. There’s also unlikely to be much harm from the occasional, as needed, conservative intervention in the horse’s mouth, power tool or otherwise. However, if someone’s intent on “correcting” your horse’s mouth be a little wary, no matter what kind of tools used. And – these are words to live by – if you’re going to use a tool – ANY tool – don’t be stupid about it.