Laminitis (or, “founder”, as it is often called) is, justifiably, one of the most feared medical and lameness conditions of the horse. I’ve been thinking about it a lot mostly because I just started taking care of two horses with chronic laminitis, and I’m hoping that I can bring them some comfort, even if I can’t get them all the way back to normal (which isn’t likely). So, I thought I’d share some thoughts.

First, off, some word history. Laminitis has been recognized as a bad condition foir horses for a long, long time. Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale” (in the Canterbury Tales, c. 1392 CE) describes a horse with founder. The word “founder” comes from Old French fondrer “collapse; submerge, sink, fall to the bottom” (the Modern French very is fondrier), which comes from the Latin word fundus (“bottom, foundation”). And, when you think about it, the word is pretty apt, because in the worst cases, the bone inside the hoof sinks – in the worst cases, it sinks all of the way out of the bottom of the hoof.

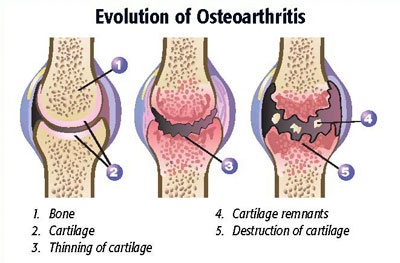

Here’s how I explain the condition to my clients. Hopefully, you’ve eaten a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. You know the paper that’s around the cup? Think of that as the hoof. The tasty stuff inside the paper? That’s the bone and everything else. The hoof is held onto the tissue inside sort of like the paper on the peanut butter cup. There are lots of little layers where the paper goes into the cup. That’s sort of the way that the hoof is held onto the bone and everything else. In the case of the hoof, the little layers are called the “laminae,” which is from the Latin word for layers. The problems with the laminae that occur in horses are collectively called laminitis.

Here’s how I explain the condition to my clients. Hopefully, you’ve eaten a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup. You know the paper that’s around the cup? Think of that as the hoof. The tasty stuff inside the paper? That’s the bone and everything else. The hoof is held onto the tissue inside sort of like the paper on the peanut butter cup. There are lots of little layers where the paper goes into the cup. That’s sort of the way that the hoof is held onto the bone and everything else. In the case of the hoof, the little layers are called the “laminae,” which is from the Latin word for layers. The problems with the laminae that occur in horses are collectively called laminitis.

To continue this analogy, let’s say that you’re taking the paper off the peanut butter cup. If you just pull back an edge a little bit, you can put the paper back and nothing is really the worse for wear. Pull the paper off the cup and you’re not going to get the paper back on – it’s not going to go back to it’s packaged “normal.” The hoof is like that, too. A little bit of damage to the laminae may not be that big a deal – too much damage and you’re, well, sunk.

Laminitis poster boy

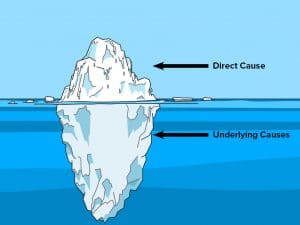

Another thing about laminitis – and this is really important – is that it’s not a single condition. Rather, laminitis is the end result of many different disease conditions of the horse, from diarrhea to PPID (Cushing’s disease), from shipping fever to uterine infections, to dietary causes, to intestinal disease, and on and on. Laminitis can result from a horse bearing too much weight on one leg (as happened in the case of the Thoroughbred race horse Barbaro), or from excessive trauma to the foot, as might occur if a horse were to go too hard and too long on ground that was too firm. The many unrelated causes can end up with a single effect: laminitis.

Because of there are so many causes, and because the presentation can be so variable (some peanut butter cups have had more paper pulled off than others, as it were), when it comes to treating the condition, it’s important to keep several things in mind.

1. Nobody – NOBODY – knows exactly what causes laminitis. There has been a lot of research done on this condition, and a lot of things are more clear than they once were. For example, we know that in many cases, insulin – the hormone that allows sugar to enter the body’s cells to provider energy – is a factor. We know that in horses with PPID, there’s lots of problems with other hormones in the horse’s body. However, veterinarians are still looking to find out exactly what factor (or factors) trigger the condition.

1. Nobody – NOBODY – knows exactly what causes laminitis. There has been a lot of research done on this condition, and a lot of things are more clear than they once were. For example, we know that in many cases, insulin – the hormone that allows sugar to enter the body’s cells to provider energy – is a factor. We know that in horses with PPID, there’s lots of problems with other hormones in the horse’s body. However, veterinarians are still looking to find out exactly what factor (or factors) trigger the condition.

ASIDE: One of my favorite sayings – and I have no idea where I heard it or who said it – is, “Experts don’t know either, but at a higher level.” Keep that in mind when it comes to treating laminitis.

2. Nobody – NOBODY – has a “cure” for laminitis. It may be possible to get the horse back to his pre-laminitic self, however, that depends on two things: what the underlying problem is and how bad the damage is. If laminitis is occurring because of some known condition – say, a uterine infection – you have to work on getting the uterine condition under control or the laminitis won’t go away. That’s why laminitis in older horses with PPID (Cushing’s) is so difficult to treat in some cases; you can’t make the problem go away because you can’t make the PPID go away. In horses in which there has been serious damage to the internal structures of the hoof, no amount of expert farriery or foot attention is going to turn the condition around. Once the paper is off, you can’t put the peanut butter cup back in the paper, as it were.

2. Nobody – NOBODY – has a “cure” for laminitis. It may be possible to get the horse back to his pre-laminitic self, however, that depends on two things: what the underlying problem is and how bad the damage is. If laminitis is occurring because of some known condition – say, a uterine infection – you have to work on getting the uterine condition under control or the laminitis won’t go away. That’s why laminitis in older horses with PPID (Cushing’s) is so difficult to treat in some cases; you can’t make the problem go away because you can’t make the PPID go away. In horses in which there has been serious damage to the internal structures of the hoof, no amount of expert farriery or foot attention is going to turn the condition around. Once the paper is off, you can’t put the peanut butter cup back in the paper, as it were.

That said, there are many different approaches to trying to help horses recover from laminitis, and it’s a good idea to know about many of them. Something that helps one horse may not help another – and some horses can’t be helped. CLICK HERE to learn more about rehabilitating a horse with laminitis.

Bottom line: If anyone tells you that they have THE cure for laminitis, feel comfortable about showing them THE door.

A wise man

3. Benjamin Franklin was right, and particularly so when it comes to laminitis. When it comes to laminitis, an ounce of prevention is always worth a pound of cure. But even here, for example, in an older horse with PPID, even your best efforts aren’t going to be enough. CLICK HERE to learn more about preventing laminitis.

Fortunately, many cases of laminitis take care of themselves. Last time I checked, it was about 50% of the horses. That doesn’t mean that an individual horse has a 50% chance of recovery – it means that about 50% of the horses that get laminitis will get better on their own because their problem was not as serious as in some horses. Ponies seem to be particularly good at getting over the problem without a whole lot of help. Of course, when treatment is prescribed for a horse that’s going to get better anyway, the treatment usually gets the credit, which is why so many different approaches to the condition can claim, “Success!”

Laminitis can be a frustrating and difficult condition for horse, horse owner, farrier, and veterinarians. Because there is no sure cure, there are many, many unrelated treatments, all of which may claim success. Your best chance of success, when it comes to dealing with laminitis, is to have a sound plan, be aware of the many treatment options, and have your veterinarian and farrier work together. The treatment options are almost limitless – there are no easy answers.

Laminitis can be a frustrating and difficult condition for horse, horse owner, farrier, and veterinarians. Because there is no sure cure, there are many, many unrelated treatments, all of which may claim success. Your best chance of success, when it comes to dealing with laminitis, is to have a sound plan, be aware of the many treatment options, and have your veterinarian and farrier work together. The treatment options are almost limitless – there are no easy answers.

And keep some peanut butter cups around – they usually help with a lot of things.