One of the coolest inventions of the 1960’s was the laser. Laser stands for “Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation,” which means almost nothing at all unless you’re a physicist (which I’m not).

In case you’re curious, here’s how they work.

The very first laser was built way back in 1960 at the Hughes Research Labs in Malibu, CA (a place where I am lucky enough to go to see horses from time to time), by an American engineer, Theodore H. Maiman. While at its core, laser is just light, it has some big differences from plain old regular light. For one, laser light is focused very tightly on a spot. And because it’s focused, it’s found all sorts of applications, such as cutting, printing, and, yes, even in medicine.

And they’re in barns, too.

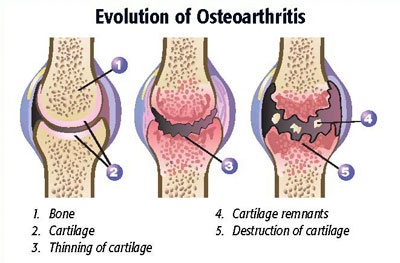

In fact, if you’ve been around a barn, you may have even seen a laser in use (on just about anything, it seems). All sorts of folks are eagerly pointing these fascinating devices at various parts of the horse, enthusiastically assuring other folks that they are doing great things. Here’s info from one company’s website: “…ideal for treating hard tissues such as bones, tendons, ligaments, teeth and thick muscles. It supports healing on many levels including: pain relief, regeneration, scar tissue reduction, anti-inflammatory, blood circulation, antibacterial, antiviral, overall joint care and it activates production of intracellular ATP (energy).” Wow. Lasers are used for a bunch of things: to treat wounds, and tendon injuries, and muscle soreness, and even so-called acupuncture “points” (I say, “so-called” because they’ve never been shown to exist as a discrete entity).

In fact, if you’ve been around a barn, you may have even seen a laser in use (on just about anything, it seems). All sorts of folks are eagerly pointing these fascinating devices at various parts of the horse, enthusiastically assuring other folks that they are doing great things. Here’s info from one company’s website: “…ideal for treating hard tissues such as bones, tendons, ligaments, teeth and thick muscles. It supports healing on many levels including: pain relief, regeneration, scar tissue reduction, anti-inflammatory, blood circulation, antibacterial, antiviral, overall joint care and it activates production of intracellular ATP (energy).” Wow. Lasers are used for a bunch of things: to treat wounds, and tendon injuries, and muscle soreness, and even so-called acupuncture “points” (I say, “so-called” because they’ve never been shown to exist as a discrete entity).

But are they worth using? Well….

Within a few years of their invention in the 1960’s, eastern European doctors were using lasers to treat just about everything. They gained some popularity in the US, too, a few decades back. Of course, they were accompanied by all sorts of glowing testimonials, but precious little in the way of real data. Like so many therapies, they became popular, and then, not so much. Now they’re back (albeit with a bit different story – more on that in a bit).

Within a few years of their invention in the 1960’s, eastern European doctors were using lasers to treat just about everything. They gained some popularity in the US, too, a few decades back. Of course, they were accompanied by all sorts of glowing testimonials, but precious little in the way of real data. Like so many therapies, they became popular, and then, not so much. Now they’re back (albeit with a bit different story – more on that in a bit).

ASIDE: This, “Once popular but now out of use,” story repeats itself throughout the history of medicine. I have books books dating back into the 17th century extolling the virtues of this or that treatment: now gone. It’s a cycle that’s seen over and over. You’d think that we’d learn.

As we begin talking about lasers, first let’s make sure we’re on the same page. “Therapeutic” lasers are, by definition, lasers that aren’t strong enough to cause direct tissue damage. They can’t cut. Nor can they heat up tissues. Thirty-plus years ago, these sorts of devices became known as “cold” lasers, a catchy phrase to be sure, and one that adds to their mystery, I think (which is mostly a good thing, when it comes to unproven treatments).

As we begin talking about lasers, first let’s make sure we’re on the same page. “Therapeutic” lasers are, by definition, lasers that aren’t strong enough to cause direct tissue damage. They can’t cut. Nor can they heat up tissues. Thirty-plus years ago, these sorts of devices became known as “cold” lasers, a catchy phrase to be sure, and one that adds to their mystery, I think (which is mostly a good thing, when it comes to unproven treatments).

There are several classes of lasers – the less powerful they are, the safer they are. Today – apparently operating according to the “bigger hammer” theory of medicine, where if some is good, more must be better – more powerful, Class IV lasers are now being used. More power is not necessarily a good thing, however, because more powerful lasers also carry the potential for harm to the eyes and to the skin (you shouldn’t look directly at them, or hold them in one place for too long, but you do get to wear goggles with them, which adds to the mystery, I think). Still, whether they do anything more than the less powerful “cold” lasers is another question entirely.

One of the wonderful things about laser therapy is that it’s really quite simple to use. It’s a point-and-shoot sort of therapy (kind of like the disposable cameras that were so popular before the digital revolution put the kibosh on the film business). You also get to fuss with the settings on the machine, which is all well and good – and certainly very impressive – except for the not-so-wonderful fact that nobody really seems to be very sure about which settings are important for the treatment of which condition, or the time needed for treatment, in addition to the disagreement about what, if anything they really do.

One of the wonderful things about laser therapy is that it’s really quite simple to use. It’s a point-and-shoot sort of therapy (kind of like the disposable cameras that were so popular before the digital revolution put the kibosh on the film business). You also get to fuss with the settings on the machine, which is all well and good – and certainly very impressive – except for the not-so-wonderful fact that nobody really seems to be very sure about which settings are important for the treatment of which condition, or the time needed for treatment, in addition to the disagreement about what, if anything they really do.

Still, the combination of being both exotic and easy to use means that, at least currently, laser therapy is undergoing something of a resurgence. To be absolutely fair, there is even some evidence supporting the use of lasers, and especially from test tube studies, where something as a result of shining laser light on cells growing in culture can often be demonstrated. Not being able to really predict the effects in the live horse, but feeling confident that they are there, laser enthusiasts throw around terms like, “photobiomodulation,” a term that sort of means that. light affects a living thing, omitting, of course, pesky details such as “What” and “How.” Like so many, many things in the horse world, the clinical use of lasers is way ahead of any evidence that supports their clinical use.

In my mind, there are three big questions that you should get answered before you go out and plunk down money for a laser machine (or a laser therapy session or eight). These are (in no particular order):

DOES THE LASER LIGHT ACTUALLY GET INTO DEEPER TISSUES?

Honestly, this question is a big deal. If laser light doesn’t get into the deeper tissues, it can’t do anything. And from both a physics and experimental standpoint, that appears to be something of a problem for laser therapy.

Ever see movies or TV shows where someone is firing a gun into a lake after the person who is trying to escape? The bullets go down into the water to a fairly shallow depth, and then they stop (and the person usually swims away and gets the bad guys in the end). Light entering tissue is sort of like that, too. A significant amount of the energy from laser light may not make it into deeper tissues because it gets absorbed by the thickness of the horse’s skin, the color of the skin (dark skin absorbs more), the water in the horse’s skin, and, of course, the hair if you haven’t clipped the leg.

Depth of penetration has been recently tested in horses, too. And it’s no really good news, at least if you’re thinking that lasers are really important in treating tendon and ligament injuries. In horse legs, researchers found that, “Only 1% to 20% and 0.1% to 4% of energy were absorbed by SDFTs and DDFTs, respectively, depending on skin color, skin thickness, and applied wavelength.” (SDFT = superficial digital flexor tendon; the “D” stands for deep). Otherwise stated, the vast majority of the laser light that gets shined on a horse’s leg is either absorbed or scattered by the skin before it gets to the tendons. To be sure, if you used a more powerful laser, you’d probably get more light into deeper tissues – it would be hard not to get more than 0.1% actually – but it’s also a fact that the skin is still going to get in the way.

DOES THE TREATMENT MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE IN THE LONG RUN?

To me, it’s really not worth paying for a treatment if you’re going to end up in the same place anyway. Let’s say, for example, that you could show that a laser would heal a wound 20% faster. Sounds good, right? But 20% faster means 4 days instead of 5, or 8 days instead of 10. Is is worth the extra time and money if the problem is going to heal, regardless? Make sure you get that question answered to your satisfaction before you start shining light on your horse.

To me, it’s really not worth paying for a treatment if you’re going to end up in the same place anyway. Let’s say, for example, that you could show that a laser would heal a wound 20% faster. Sounds good, right? But 20% faster means 4 days instead of 5, or 8 days instead of 10. Is is worth the extra time and money if the problem is going to heal, regardless? Make sure you get that question answered to your satisfaction before you start shining light on your horse.

WHAT IS THE EVIDENCE THAT IS WORKS FOR A PARTICULAR CONDITION?

In my mind, given the recent study on light absorption, there’s not a lot of reason to use lasers – especially “cold” ones – in an attempt to do therapy (add imaginary “points” into the mix and you’re kind of out on a limb that’s not attached to a tree). Nevertheless, there have been many studies done, and you should ask to see them before you start paying for the treatments.

For example, even though light absorption issue isn’t really an issue when it comes to wound treatments, the data is not all that great. Late in 2015. someone had the temerity to do a good study in dogs that didn’t work out so well for lasers. Back in 1999, low level lasers didn’t affect wound healing in horses.

I’m just saying. Look before you leap.

SO SHOULD YOU LASER YOUR HORSE?

Currently, at least in some circles, laser therapy has become something of a cure-all. Treatments are usually sold in packages, and advocates of laser therapy are very committed (for better or worse). What bothers me – like so many things in the horse world – is that based solely on naive optimism, good intentions, and unsupported claims, horse owners may dump all sorts of money into lasering this and that, and thereby exhaust funds that could otherwise be used for things that are really helpful in maintaing a horse (brushes, hoof picks, horse treats, etc.), or even on treatments that actually do help. At this point, the science just doesn’t back up the current practice.

Currently, at least in some circles, laser therapy has become something of a cure-all. Treatments are usually sold in packages, and advocates of laser therapy are very committed (for better or worse). What bothers me – like so many things in the horse world – is that based solely on naive optimism, good intentions, and unsupported claims, horse owners may dump all sorts of money into lasering this and that, and thereby exhaust funds that could otherwise be used for things that are really helpful in maintaing a horse (brushes, hoof picks, horse treats, etc.), or even on treatments that actually do help. At this point, the science just doesn’t back up the current practice.

Laser therapy certainly hasn’t shown any unequivocal evidence that it’s effective for any condition. Even in situations where laser use isn’t completely implausible – such as treatment of wounds, where the laser light isn’t absorbed by the horse’s skin – the optimum wavelengths or intensities or treatment intervals aren’t known, and the scientific evidence isn’t that good. We know that the explanations given – increasing blood flow, and such – aren’t really supported by good science in living horses. And while you can find some interesting effects that have occurred in the test tube, and I suppose that’s “promising,” horses don’t live in test tubes.

I’d love for lasers to work; I really would. But after 60 years or so, I think it’s probably worth waiting a bit longer to sign up.