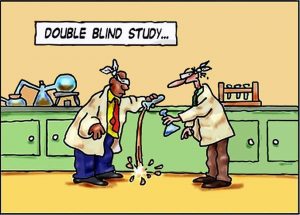

I want to start off by saying that I take care of horses’ teeth, that occasionally horses’ teeth need taking care of, and that, occasionally, horses’ teeth can cause problems for the horse.

I want to start off by saying that I take care of horses’ teeth, that occasionally horses’ teeth need taking care of, and that, occasionally, horses’ teeth can cause problems for the horse.

It can sometimes kind of go downhill from there, however.

Among the many, many products and services – supplements, injections, adjustments, magnetizers, light machines, movers, shakers, etc., etc. – that have come along with the rise of “performance horse medicine” is performance horse dentistry. Otherwise stated, it may be asserted that for a horse to perform at his best, it may be necessary to grind, cut, shave, or otherwise “equilibrate” a horse’s mouth to ensure that it can run, jump, piaffe, cut, or slide to the best of his ability. On some level, I suppose, this makes some sense, I mean, it wouldn’t be a good thing for a horse to try to perform with a tooth that was causing him pain because that tooth was broken or infected, to name just one example. However, a broken tooth is real pathology – what’s being recommend to horses as important to “correct” often isn’t. That’s why the whole idea of “performance horse” dentistry as it is often marketed to horse owners begs to be examined a bit. Let’s do it.

See what a difference good dental care can make?

Right off the bat, I might note that, when it comes to other athletes, say, basketball players, the care of the teeth is apparently entrusted to regular old run of the mill dentists. That is, at least to my knowledge, there aren’t any human dental specialists who assert that their particular method of, say, scaling teeth, or filling cavities, is going to help someone make more three-pointers or rebound with any greater aplomb; when it comes to rebounding, for example, you can’t polish enough enamel to get someone to be 7 feet tall. And while I digress a bit (not uncommon for me, to be sure), it does seem to me that whether a horse is a “performance” horse or one that just meanders around burning hay, waiting for the occasional opportunity to shuffle absent-mindedly along the trail, the teeth are fundamentally the same. And, honestly, just about anyone who has the inclination to work on a horse’s mouth seems anxious to do it, at least when it comes to “routine” care, which, sadly, is why so many people with limited training seem ready to jump into the horse’s mouth with limited (if any) training, all the while calling themselves “specialists” in the process.

Of course, it could be that I’m wrong. But after over four decades of taking care of horses’ mouths, including the mouths of some of the best performance horses on the planet, I thought it might be worth taking a look at what we thought we knew, what we think we know, and try to draw some conclusions from there.

Of course, it could be that I’m wrong. But after over four decades of taking care of horses’ mouths, including the mouths of some of the best performance horses on the planet, I thought it might be worth taking a look at what we thought we knew, what we think we know, and try to draw some conclusions from there.

From a historical perspective, “performance horse” recommendations have changed a lot. Take, for example, three procedures used to be very commonly advocated. The first is cutting the canine teeth. The second is the “bit seat.” The third is pulling the wolf teeth (this one still gets a lot of interest, honestly). I could go on for some time about each procedure, but there’s only so much that people are willing to read. Let’s suffice it to say that during the course of my career, each of these procedures has gone through a period of time where it was enthusiastically advocated: at conferences, seminars, wet labs, and such. I read about the procedures, I learned how to do them, and, in some cases, I even did them. I just couldn’t tell any difference in how the horses did after I did them.

And now? Well, exactly none of those procedures is now uniformly endorsed as something that’s routinely needed, at least endorsed by most veterinarians with advanced training in equine dentistry (there aren’t very many, but they do exist). Otherwise stated, many dental specialists are now recommending exactly the opposite of what was recommended in the very recent past. All three of the procedures have gone from something that you always needed to do to something that you should almost never need to do (if ever). The horses? They still seem to be doing OK, in spite of us.

And now? Well, exactly none of those procedures is now uniformly endorsed as something that’s routinely needed, at least endorsed by most veterinarians with advanced training in equine dentistry (there aren’t very many, but they do exist). Otherwise stated, many dental specialists are now recommending exactly the opposite of what was recommended in the very recent past. All three of the procedures have gone from something that you always needed to do to something that you should almost never need to do (if ever). The horses? They still seem to be doing OK, in spite of us.

The only way I can make sense out of this is that, at least when it comes to these three procedures for performance horses, it probably didn’t make any difference. I mean, if you eagerly do something, and then later, you just as eagerly avoid it, and there’s absolutely no change, it’s pretty hard to assert that the something you did was ever important. In fact, when it comes to medicine, and history, there are a lot of such examples (far too many). But this article is about performance horse dentistry, so let’s move on.

There is scientific way of looking at whether routinely grinding on horse teeth makes a difference in performance horses. That would be to take one group of horses and grind away, and take another group of horses and do nothing at all. Don’t tell the riders. See how it goes. This is what’s called a “blinded” study, that is, the evaluators (riders) don’t know what was done (they are “blinded” to the procedure). Of course, the horse doesn’t know what or why it’s being done anyway, so even though you can’t blind them, you don’t need to.

There is scientific way of looking at whether routinely grinding on horse teeth makes a difference in performance horses. That would be to take one group of horses and grind away, and take another group of horses and do nothing at all. Don’t tell the riders. See how it goes. This is what’s called a “blinded” study, that is, the evaluators (riders) don’t know what was done (they are “blinded” to the procedure). Of course, the horse doesn’t know what or why it’s being done anyway, so even though you can’t blind them, you don’t need to.

ASIDE: I have always wondered why horses are willing to put up with dental interventions: heck, all sorts of things that we do to them.

Person: “Hi horse, I’m going to grind on your teeth.”

Person: “Hi horse, I’m going to grind on your teeth.”

ANSWER 1 – Horse: “OK – I’m not really sure what you’re doing, but OK.”

ANSWER 2 – Horse if if were me: Bite, strike, kick, run, tear down the barn. That, I understand.

Anyway, to complete the scientific circle, you’d want to repeat any study that you did. That is, you’d want to confirm the results of one study with another study. If both studies showed the same thing, you’d have more confidence in what you’re seeing. Turns out that when it comes to performance horse dentistry, that’s just been done.

Franches-Montagnes horses, doing an impression of many other horse breeds

Recently, Swiss investigators looked at 38 Franches-Montagnes stallions (also known as Freibergers, which, by the way, is a breed that has been around since 1619).

ANOTHER ASIDE: I have never seen one of these horses, so here’s a picture.

When it comes to scientific confirmation, this is not the first good study to come to this conclusion. In 2006, in Canada, riders couldn’t tell the difference between 11 horses that got “occlusal equilibration” and 5 that didn’t. Dressage test scores and movements didn’t get better on horses after their teeth were filed down.

LAST ASIDE: I have no idea why the investigations are being done on dressage horses, but that’s the way it is. Still – and to be frank – as picky as dressage riders can be, you’d think if there were a difference, they might be the ones to notice, particularly the pros.

Having just told you that, based on research, we can say with some confidence that “routine” performance horse dentistry in a normal horse’s mouth seems to not make any difference at all in how performance horses actually perform, I don’t want you to go about ignoring your horse’s mouth. Quite the contrary. What I’d like you to do is get your horse’s mouth examined periodically to make sure that there aren’t any problems, but not do ANYTHING unless you find a real problem. Revolutionary idea, I’m sure, the idea that you shouldn’t do a procedure unless there’s a need for a procedure, but that’s how I work. And for goodness sakes, routine care of the horse’s mouth doesn’t require a ton of advanced training and doesn’t need to be exclusively performed by “specialists.” Any good veterinarian with a modicum of interest in equine dental care should be able to take care of most horses’ mouths. If there is a real problem, it should be treated, of course, but by a real specialist (that is, either by a veterinarian with advanced dentistry training, or a trained veterinary surgeon).

Having just told you that, based on research, we can say with some confidence that “routine” performance horse dentistry in a normal horse’s mouth seems to not make any difference at all in how performance horses actually perform, I don’t want you to go about ignoring your horse’s mouth. Quite the contrary. What I’d like you to do is get your horse’s mouth examined periodically to make sure that there aren’t any problems, but not do ANYTHING unless you find a real problem. Revolutionary idea, I’m sure, the idea that you shouldn’t do a procedure unless there’s a need for a procedure, but that’s how I work. And for goodness sakes, routine care of the horse’s mouth doesn’t require a ton of advanced training and doesn’t need to be exclusively performed by “specialists.” Any good veterinarian with a modicum of interest in equine dental care should be able to take care of most horses’ mouths. If there is a real problem, it should be treated, of course, but by a real specialist (that is, either by a veterinarian with advanced dentistry training, or a trained veterinary surgeon).

ASIDE: I have had the experience of an “equine dentist” tell a client that the horse’s mouth needed to be seen by a veterinarian (me) because of a tooth problem the horse had. The irony was not lost on me.

Don’t ignore your horse’s mouth. But don’t get all happy thinking that there’s some secret that only highly trained specialists know that is going to be the difference between your Olympic dreams and being destined to trip over 0.5 meter fences for the rest of your life. Have your horse’s mouth checked every once in a while. Have it checked by someone who is willing to do nothing, if nothing is what is needed.

Don’t ignore your horse’s mouth. But don’t get all happy thinking that there’s some secret that only highly trained specialists know that is going to be the difference between your Olympic dreams and being destined to trip over 0.5 meter fences for the rest of your life. Have your horse’s mouth checked every once in a while. Have it checked by someone who is willing to do nothing, if nothing is what is needed.

LAST ASIDE: In fact, I think I’s a good general rule try to avoid specialists when it can’t be shown that specialists really make any difference. If the only tool that you have is a hammer, pretty soon everything starts to look like a nail.

And as long as we’re exploding myths, there’s one other thing. If you get a gift horse, it’s actually OK to look it in its mouth. Just don’t do anything to it unless he needs it.