In the last decade or so, horse owners and veterinarians have been pounded over the head with the promise of “regenerative” therapies. These “cutting edge” therapies purport to help horses recover from injuries or degenerative conditions quicker/stronger/better than ever before.

In the last decade or so, horse owners and veterinarians have been pounded over the head with the promise of “regenerative” therapies. These “cutting edge” therapies purport to help horses recover from injuries or degenerative conditions quicker/stronger/better than ever before.

Frankly, I’m a bit over it. In fact, I’m somewhat embarrassed that the veterinary profession is associated with the term. What is usually sold as a treatment full of promise is, in fact, something of a boondoggle, and one that’s been applied with little attention to how such therapies should be used, at least from an ethical point of view.

What got my blood boiling was a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association, talking about the problems with these so-called “regenerative” therapies (you know, stem cells, PRP, and the like). You can see the article if you CLICK HERE.

Let’s start with the name. Like most things that folks are trying to sell you, the name is important. Most of the world seems to like a name that sounds important. So, for example, if someone told you were drinking a, “Symbiotic growth of acetic acid bacteria and osmophilic yeast species in a zoogleal mat,” you might be less excited than if you were told you were drinking, “Kombucha, a traditional drink from China.” Why would you want to be a Dishwasher when you could be a Gastronomical Hygiene Technician? Who wouldn’t rather be an Education Center Nourishment Consultant instead of a School Lunch Server? Names are important.

Let’s start with the name. Like most things that folks are trying to sell you, the name is important. Most of the world seems to like a name that sounds important. So, for example, if someone told you were drinking a, “Symbiotic growth of acetic acid bacteria and osmophilic yeast species in a zoogleal mat,” you might be less excited than if you were told you were drinking, “Kombucha, a traditional drink from China.” Why would you want to be a Dishwasher when you could be a Gastronomical Hygiene Technician? Who wouldn’t rather be an Education Center Nourishment Consultant instead of a School Lunch Server? Names are important.

The name “regenerative” really draws you in. It’s a big deal. It’s also a bit of linguistic sleight of hand. The word “regenerative” is actually pretty easy to define. To “regenerate” means to regrow new tissue and/or to replace lost or injured tissue. When it comes to treating injured tissue, such a “regenerative” therapeutic thing would be truly revolutionary, akin to finding the Holy Grail of tissue repair. Imagine if with one or two shots of a “regenerative” therapy, an injured structure could be returned to new – or almost new – and the horse could go on as before. That’s these therapies are sometimes sold, anyway. Regenerative therapies are said to be bigger, better, and faster than anything that ever came before.

But here’s an inconvenient fact. There is no convincing evidence of a truly regenerative effect for any treatment in veterinary medicine (stem cells, PRP, lasers, etc., etc.). Think about it. You’ve got any number of therapies being sold as “regenerative” when there’s really no evidence at all that any of them do any such thing.

But here’s an inconvenient fact. There is no convincing evidence of a truly regenerative effect for any treatment in veterinary medicine (stem cells, PRP, lasers, etc., etc.). Think about it. You’ve got any number of therapies being sold as “regenerative” when there’s really no evidence at all that any of them do any such thing.

I think it’s wrong.

Not that the idea of something that regenerates living tissue is unappealing. The idea of some treatment that would restore things to as good as new has been around for centuries. So, for example, back in 1513, Juan Poncé de Leon (better known as Poncé de Leon) led the first expedition to La Florida. Accounts after his death suggest that he may have been looking for a “Fountain of Youth,” that is, waters that would help reverse the aging process (actually vitality-restoring waters are something of a constant in history, and long before Poncé de Leon). Needless to say, Poncé de Leon’s not still here (he died of battle wounds in 1521). People are still apparently still looking for that medical fountain. Sadly, some folks out there will tell you they’ve found it.

Juan Ponce de Leon, at his optimistic best

What’s got me so annoyed about “regenerative” therapies is that, from an ethical standpoint, a therapy should have more than “promise,” or, at least, if it only offers “promise,” you should know that before agreeing to use it on your horse. If a therapy offers only promise and the effects haven’t been proven, the correct word for the treatment is “experimental.” There’s nothing wrong with an experimental treatment, of course. There are many therapies needed to treat many conditions. But it’s one thing to have a person agree to participate in an experiment with their horse; it’s quite another to sell that person on the “promise” of an attractively-named therapy and not bother to keep track of the results.

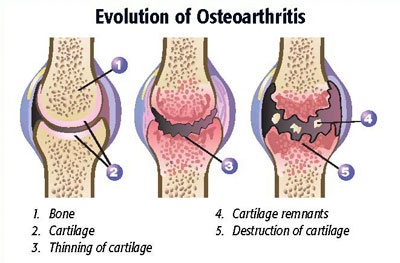

Over the past decade or so, unproven regenerative medicine therapies have been offered to horse owners for the treatment of conditions from arthritis to tendon and ligament injuries, from wounds to eye problems. The fact remains that the safety and efficacy of regenerative medicine products hasn’t been shown in any species (with the exception of a narrow range of indications in human medicine).

Over the past decade or so, unproven regenerative medicine therapies have been offered to horse owners for the treatment of conditions from arthritis to tendon and ligament injuries, from wounds to eye problems. The fact remains that the safety and efficacy of regenerative medicine products hasn’t been shown in any species (with the exception of a narrow range of indications in human medicine).

Regenerative medicine products can come from a horse’s own bone marrow or fat, from tissue obtained at birth (like placenta of umbilical cord blood), from blood, or even from other horses. They can be produced in commercial labs or in machines sold to veterinarians. And no matter what you’ve heard:

- The products have not been shown to be effective

- They are not inherently safe, whether they come from the same horse or another horse.

In human medicine, the use of these products appears to be widespread. An increasing number of adverse events is being reported. We really don’t know about adverse effects in horses because nobody seems to be keeping track.

To me, the main problem with the “promise” of regenerative therapies is that very few people seem to want to call “regenerative” therapies what they are. They’re not “promising,” “cutting edge,” “novel” or any other positive verbiage that might entice someone to use them. Regenerative therapies are quite simply this: they are investigational procedures for which safety and effectiveness is mostly not available. In fact, very few people are even bothering to track them. It’s mostly just testimonials and promise (and a good bit of that promise comes from the same folks that produce the therapies).

To me, the main problem with the “promise” of regenerative therapies is that very few people seem to want to call “regenerative” therapies what they are. They’re not “promising,” “cutting edge,” “novel” or any other positive verbiage that might entice someone to use them. Regenerative therapies are quite simply this: they are investigational procedures for which safety and effectiveness is mostly not available. In fact, very few people are even bothering to track them. It’s mostly just testimonials and promise (and a good bit of that promise comes from the same folks that produce the therapies).

In human medicine, things got so bad in the “regenerative” space that, in 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning to consumers about stem cell therapies. The FDA action put a little bit of a damper on stem cells in the veterinary world, but they’re still out there, promising away.

He’s counting on you

Regenerative therapies appeal to vulnerable horse owners, who want the “best” for their horses. They also appear to veterinarians, many of whom don’t want to get left out of a therapy that could help increase a horse’s health and well-being. The potential advantages of new treatments are usually clear, but in the rush to be “cutting edge,” concerns about ethics, safety, and financial loss to the horse owner often get left behind. “Promise” is important, but so is good science, good record keeping, and transparent engagement with the horse-owning public.

So, if it’s proposed that your horse get some sort of “regenerative” therapy, before you say, “Yes,” here’s what you should do.

Ask if the therapy that is being proposed is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (or other governmental overseeing body).

Ask if the therapy that is being proposed is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (or other governmental overseeing body).- Ask if your horse is taking part in a clinical trial. If he is, you shouldn’t have to pay for the therapy. If he isn’t part of a clinical trial, think twice about paying for it.

- Ask for documentation of results from other horses who have been treated, comparing how treated horses did in comparison to non-treated horses.

- Ask for an informed consent statement, read it, and only sign it if you think it’s a good idea.

- Ask where you should report adverse reactions.

- If you have an adverse reaction, report it.

It is long past the time that unproven and unapproved regenerative medicine products be called what they usually are: uncontrolled experimental procedure that horse owners are being asked to pay for. I think that veterinary medicine should do a lot better when it comes to suggesting such therapies. Demand it.