I thought it might be time to talk about a certain vitamin that seems to be at the forefront of many discussions about horse nutrition these days: Vitamin E. To be completely accurate, Vitamin E is not really one vitamin, it’s a group of eight compounds that can be dissolved in fat (for you chemistry buffs, that’s four tocopherols and four tocotrienols). Nevertheless, as with many/most things that raise anxiety among horse owners, there’s a lot of misinformation to sort through, much of which isn’t very accurate, particularly if you’re trying to use Dr. Google. So,let’s take a look.

I thought it might be time to talk about a certain vitamin that seems to be at the forefront of many discussions about horse nutrition these days: Vitamin E. To be completely accurate, Vitamin E is not really one vitamin, it’s a group of eight compounds that can be dissolved in fat (for you chemistry buffs, that’s four tocopherols and four tocotrienols). Nevertheless, as with many/most things that raise anxiety among horse owners, there’s a lot of misinformation to sort through, much of which isn’t very accurate, particularly if you’re trying to use Dr. Google. So,let’s take a look.

Casimir Funk (really)

Of course, while all vitamins have been important for, well,ever, they were first named in the early 20th century, thanks to the efforts of Polish biochemist Casmiir Funk. The term “vitamin” comes from a combination of “vital,” which they are, plus “amine” which refers to an amino acid, which vitamins were once thought to have, but actually don’t. So, even the name has some misinformation in it.

Vitamin E has all sorts of functions in the horse’s body,including but not limited to, and in no particular order, for the eyes, the reproductive tract, and the neuromuscular system. The most important function of Vitamin E seems to be a biological antioxidant. Rather than go into a dissertation on oxidant and antioxidant chemistry, suffice it say that some biological processes produce oxidants, which are commonly thought to be “bad,” rightly or wrongly. Substances such as Vitamin E that neutralize oxidants (thus, “anti”-oxidants) are generally thought to be “good.” By doing such good anti-oxidant work, and probably by other ways that we haven’t figured out yet but are sure to generate many PhD dissertations, Vitamin E serves to maintain many normal body functions of the horse.

Problems related to Vitamin E generally show up as problems in the way that the horse moves around (as a result of problems in the horse’s neuromuscular system). There are a whole host of multi-syllabic problems described related to vitamin E deficiency in both young and old horses. In young horses, these include nutritional myodegeneration, neuroaxonaldystrophy, and equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy; in older horses, a lack of vitamin E is associated with vitamin E deficient muscle problems or equinemotor neuron disease.

Problems related to Vitamin E generally show up as problems in the way that the horse moves around (as a result of problems in the horse’s neuromuscular system). There are a whole host of multi-syllabic problems described related to vitamin E deficiency in both young and old horses. In young horses, these include nutritional myodegeneration, neuroaxonaldystrophy, and equine degenerative myeloencephalopathy; in older horses, a lack of vitamin E is associated with vitamin E deficient muscle problems or equinemotor neuron disease.

ASIDE: The bottom line, so far, is that horses need vitamin E and that a lack of vitamin E is mostly not a good thing for horses.

“So,” you say, “How do I keep my horse from having problems related to Vitamin E?”

The best Vitamin E supplement

Happily, for most horses, this is really a rather simple question to answer. You let them eat grass. As it turns out, green grass is a great source of vitamin E: most things that are green contain a good bit of it. Those horses that are lucky enough to have access to green grass also get lots of vitamin E. They don’t need to have access to green grass every day, either. In fact, horses store vitamin E quite well (in fat cells). This, then, explains why horses that don’t have access to green grass in the winter don’t immediately start showing problems related to a lack of Vitamin E. The fact that they store Vitamin E also explains why an adult horse has to go something like 18 months without access to Vitamin E before problems start to be seen.

TWO TAKE HOME POINTS:

- For horses that get to eat green grass, Vitamin E is usually not something to be concerned about.

- Horses don’t need to get some minimum amount of Vitamin E every day, because they store it. If you’ve had enough Vitamin E for a while, it’s kind of like being fat – a few days with without calories won’t kill you because there are calorie deposits to be drawn from.

Namib Desert Horses, North Africa

But some horses do have problems related to vitamin E.

Some horses are not so lucky as to always have access to green grass. Southern California, where I live and practice, is one of those spots. For most of the year, grass is in short supply, and even when it’s growing, horses mostly don’t get to pasture on it. As a result, you’d think that I’d see a lot of problems with vitamin E deficiencies in horses.

But I don’t.

Which brings up another point. Like most things in medicine, it’s complicated. Not all horses show signs of Vitamin E deficiency, even when you think that they should. In fact, even when a whole herd is likely to be deficient in Vitamin E, only certain horses show clinical signs. Whether or not a horse ever shows problems related to a Vitamin E deficiency relates to things such as the age of the horse when deficiency develops, how long the horse was deficient, genetics, other dietary deficiencies or excesses, and probably a whole bunch of other things that we don’t know about. In fact, in many horses, there are no apparent bad effects of a Vitamin E deficiency at all. That’s why you can’t just draw blood, check vitamin E levels, and be sure that a horse actually has a serious problem. A proper diagnosis of a Vitamin E related problem is made with a combination of Vitamin E status, clinical signs, muscle biopsy results, as well as eliminating other diseases that have similar signs (all of this would be subject for another article – or a book, for that matter). For what its’ worth, a normal blood serum vitamin E level for a horse is considered to be greater than 2 μg/ml (micrograms/milliliter).

Which brings up another point. Like most things in medicine, it’s complicated. Not all horses show signs of Vitamin E deficiency, even when you think that they should. In fact, even when a whole herd is likely to be deficient in Vitamin E, only certain horses show clinical signs. Whether or not a horse ever shows problems related to a Vitamin E deficiency relates to things such as the age of the horse when deficiency develops, how long the horse was deficient, genetics, other dietary deficiencies or excesses, and probably a whole bunch of other things that we don’t know about. In fact, in many horses, there are no apparent bad effects of a Vitamin E deficiency at all. That’s why you can’t just draw blood, check vitamin E levels, and be sure that a horse actually has a serious problem. A proper diagnosis of a Vitamin E related problem is made with a combination of Vitamin E status, clinical signs, muscle biopsy results, as well as eliminating other diseases that have similar signs (all of this would be subject for another article – or a book, for that matter). For what its’ worth, a normal blood serum vitamin E level for a horse is considered to be greater than 2 μg/ml (micrograms/milliliter).

The two types of Vitamin E supplements

So, after all that, let’s say that you think you’d like to give your horse some extra Vitamin E. You should probably do this on the advice of your veterinarian, or from someone with a degree in equine nutrition, since it is at least theoretically possible to give too much Vitamin E (too much Vitamin E, like too much of many good things, is potentially harmful). You should also pay attention to the Vitamin E that you’re giving, because it comes in two main types, either “natural” or synthetic. Here’s a case where “natural” really is better. But you have to read the label.

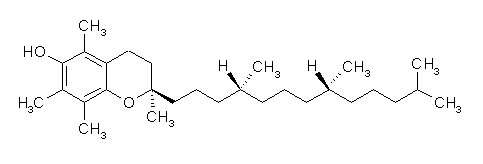

The “natural” form of Vitamin E is in an “RRR” form (we are not going to talk about chemistry here – it’s on the label). This form can either come in a powder, (RRR-αTocopherol acetate), or as a water-dispersible liquid (RRR-αTocopherol). By the way, in case you’re not up on your Greek alphabet, α is the Greek small letter for “alpha.” Regardless, the powder is more stable, has a longer shelf-life, but isn’t absorbed quite as well as is the liquid.

RRR_alpha-tocopherol (just so’s you know)

The “synthetic” form of Vitamin E is spelled differently. You’ll usually see things like “All-rac-α-Tocopheryl acetate,” or “dl- α-Tocopheryl-acetate” on the label. Look at the end of the Tocopher-part of the word; the synthetic form has an “-yl” instead of an “-ol.” I’m sure that the folks making such forms have the best of intentions, but the fact is that the “synthetic” form of Vitamin E is not absorbed as well by the horse as is the “natural” form. Thus, if you’ve decided that it’s best to supplement with vitamin E – which, to be clear, most people don’t need to do, except in specific circumstances – it makes sense to use the vitamin E formulation that the horse can use most efficiently.

The “synthetic” form of Vitamin E is spelled differently. You’ll usually see things like “All-rac-α-Tocopheryl acetate,” or “dl- α-Tocopheryl-acetate” on the label. Look at the end of the Tocopher-part of the word; the synthetic form has an “-yl” instead of an “-ol.” I’m sure that the folks making such forms have the best of intentions, but the fact is that the “synthetic” form of Vitamin E is not absorbed as well by the horse as is the “natural” form. Thus, if you’ve decided that it’s best to supplement with vitamin E – which, to be clear, most people don’t need to do, except in specific circumstances – it makes sense to use the vitamin E formulation that the horse can use most efficiently.

The dietary requirement for Vitamin E was last examined back in2007, and it was set at 1-2 IU/kg of body weight. (IU stands for “International Unit,” and an IU is defined individually for each substance that is measured with IU’s.) In cases where supplementation is recommended,for horses, doses are usually along the lines of 5000 – 10,000 IU per day. Dosing with the liquid works great but it’s pricey. Dosing with the powder works, too, but you need a higher dose and longer periods of time. Even so, the best and least expensive way to supplement your horse with vitamin E is to get him to eat grass for at least six months a year. Which should make both of you happy.

All that said, there are still some caveats. In no particular order:

Some horses don’t respond to Vitamin E supplementation, even when it’s correctly supplemented, and a good number of horses that develop problems related to a lack of Vitamin E don’t respond even when given Vitamin E.

Some horses don’t respond to Vitamin E supplementation, even when it’s correctly supplemented, and a good number of horses that develop problems related to a lack of Vitamin E don’t respond even when given Vitamin E. - There’s an injectable form of vitamin E available for horses (it also contains selenium), however, it doesn’t contain enough bioavailable Vitamin E to make any difference.

- If you’re going to supplement with Vitamin E, do it for a specific reason, and check to see if it’s doing any good (with serum tests).

- If your horse’s Vitamin E levels are more than4 μg/ml (micrograms/milliliter) they’re too high. More is not better.

- Giving extra vitamin E to any horse with a neurological problem or muscle problem doesn’t really make much sense if the horse has normal serum vitamin E levels.

Just giving Vitamin E because it’s “good” or just because you think that your horse might have some problem doesn’t make a lot of sense. In human medicine, where Vitamin E supplementation used to be the rage, and probably still is in some circles, there is little in the way of good research to showing that Vitamin E supplements help anything. Most good human trials from the past few years have given inconclusive, or even negative results, and Vitamin E supplements might actually be harmful in some circumstances.

Just giving Vitamin E because it’s “good” or just because you think that your horse might have some problem doesn’t make a lot of sense. In human medicine, where Vitamin E supplementation used to be the rage, and probably still is in some circles, there is little in the way of good research to showing that Vitamin E supplements help anything. Most good human trials from the past few years have given inconclusive, or even negative results, and Vitamin E supplements might actually be harmful in some circumstances.

Most horses get plenty of Vitamin E in their diets. There are specific indications and specific problems related to Vitamin E, but Vitamin E problems are not particularly common in most areas. Vitamin E is fairly expensive – happily, even if your horse is currently lacking in Vitamin E, he shouldn’t need it continuously: he’ll also store it in fat cells for future use (normal, healthy horses do have some fat in them). And if you’re concerned, reach out to your veterinarian or an equine nutritionist. He or she will be happy to help.