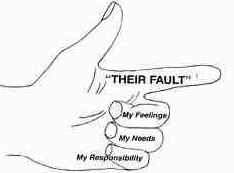

BEFORE WE GET STARTED, I want to make it clear that I’m not trying to point the finger of blame at anyone in particular by writing this article. But the cost of veterinary care is a complex, and important issue. I found something written about human medicine that really made me think. Maybe it will make you think, too.

BEFORE WE GET STARTED, I want to make it clear that I’m not trying to point the finger of blame at anyone in particular by writing this article. But the cost of veterinary care is a complex, and important issue. I found something written about human medicine that really made me think. Maybe it will make you think, too.

In surveys conducted by the American Veterinary Medical Association, the number one concern of animal owners is the cost of care. Cost is one reason why veterinary visits may be declining in some areas – it’s why some animals never get to see a veterinarian. For example, close to 50% of horses in the United States never saw a veterinarian in 2011 (the last year for which I could find statistics).

We have to agree that if you’re going to have a veterinarian see your horse, he or she should get paid for it. I mean, nobody begrudges someone else the right to make a living (I hope). Nobody is going to expect a veterinarian to come out and check over a horse for free, or give away medication or suture material that the veterinarian had to pay for, right? There has to be some cost.

We have to agree that if you’re going to have a veterinarian see your horse, he or she should get paid for it. I mean, nobody begrudges someone else the right to make a living (I hope). Nobody is going to expect a veterinarian to come out and check over a horse for free, or give away medication or suture material that the veterinarian had to pay for, right? There has to be some cost.

But understanding all that, the fact of the matter is that costs keep rising. The cost of some medications and procedures can be exceedingly expensive. In some cases, I think that’s completely understandable. Take colic surgery (please). If a horse has a major surgery in the middle of the night, and has 24 hour care for a couple of weeks, it’s bound to be an expensive undertaking: it almost has to be. But sometimes, even the cost of what-would-seem-to-be pretty straight-forward care for routine problems can seem out of control. Sometimes even I shake my head over the cost of some of the stuff with which I’m presented.

The question of who is responsible for the increasing cost of care has not been studied in veterinary medicine; at least, if it has been, I haven’t been able to find the study. Contrast that to human medicine, where keeping costs down is generally considered to be a goal of the overall health care system (if you didn’t know, the US has the most expensive health care system in the world). So, to look at the question of health care costs, and what’s driving them, enter the renowned Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Their conclusions are very interesting, and, in my opinion, have a lot of possible parallels in veterinary medicine (and they don’t just apply to veterinarians).

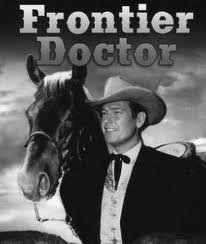

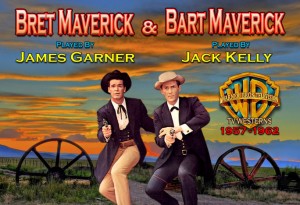

In 2013, the Dartmouth group published a paper in the National Bureau of Economic Research. No, I don’t normally read the NBER, but you can read the article – all 58 dense pages of it – if you CLICK HERE. What sticks out – to me anyway – is that a major part of the cost of health care in humans is actually driven up by two groups of physicians. Dartmouth researchers call the first group. “Cowboy Doctors,” that is, doctors who consistently recommend care that isn’t indicated by current clinical guidelines. They call the second group, “Comforters,” that is, doctors who consistently recommend medical care that aims to improve the quality of life, even if it can’t fix the problem (it’s generally given to people with serious or terminal illnesses).

In 2013, the Dartmouth group published a paper in the National Bureau of Economic Research. No, I don’t normally read the NBER, but you can read the article – all 58 dense pages of it – if you CLICK HERE. What sticks out – to me anyway – is that a major part of the cost of health care in humans is actually driven up by two groups of physicians. Dartmouth researchers call the first group. “Cowboy Doctors,” that is, doctors who consistently recommend care that isn’t indicated by current clinical guidelines. They call the second group, “Comforters,” that is, doctors who consistently recommend medical care that aims to improve the quality of life, even if it can’t fix the problem (it’s generally given to people with serious or terminal illnesses).

The Darmouth group found that they can explain over half of the variation in end-of-life spending costs in human health care simply by knowing about the attitude of the doctor involved in care. That is, if the doctor is a “Cowboy” or a “Comforter,” you can be pretty sure that your health care is going to be more expensive than if you didn’t have someone from one of those groups. In fact, the Dartmouth group concluded that 36% of end-of-life spending, and 17% of all US health care spending is associated with with physician beliefs in procedures that aren’t supported by good evidence of effectiveness. It’s a half-a-trillion-dollar problem.

The Darmouth group found that they can explain over half of the variation in end-of-life spending costs in human health care simply by knowing about the attitude of the doctor involved in care. That is, if the doctor is a “Cowboy” or a “Comforter,” you can be pretty sure that your health care is going to be more expensive than if you didn’t have someone from one of those groups. In fact, the Dartmouth group concluded that 36% of end-of-life spending, and 17% of all US health care spending is associated with with physician beliefs in procedures that aren’t supported by good evidence of effectiveness. It’s a half-a-trillion-dollar problem.

I think cowboys and comforters are something of a problem in veterinary medicine, as well.

Honestly, I don’t think that most veterinarians think that they are part of the problem at all (I’m not ever sure that some think that cost of care is an issue). In veterinary discussions, I often hear things like, “Well, the client wanted the treatment,” or, “They won’t be happy unless I do everything.” In some cases, perhaps those things are true. And it turns out that human physicians sometimes justify expensive and/or unnecessary procedures using exactly the same lines of thinking. You see, if you do “everything,” it’s something of a win:win situation, because if the patient gets better, the doctor gets the credit, but if the patient gets worse, the doctor can say that he or she did everything possible.

But, according to the study, there’s just one problem with these lines of justification: they mostly aren’t true. Costs don’t keep rising simply because people keep demanding more expensive treatments. Really, are you out there asking to spend as much money as possible on treating your horse? In human medicine, as it turns out, the biggest reason that costs keep going up is not patient demand (in veterinary medicine, it would be client demand, of course), it’s differences in physician beliefs about how well a particular therapy works.

But, according to the study, there’s just one problem with these lines of justification: they mostly aren’t true. Costs don’t keep rising simply because people keep demanding more expensive treatments. Really, are you out there asking to spend as much money as possible on treating your horse? In human medicine, as it turns out, the biggest reason that costs keep going up is not patient demand (in veterinary medicine, it would be client demand, of course), it’s differences in physician beliefs about how well a particular therapy works.

I think that’s likely to be the case in veterinary medicine, too.

Cowboys and Comforters

Cowboy doctors go it alone, just like the name implies. They have their own rules and beliefs, and aren’t really constrained by the shackles of clinical evidence. They’ll justify a procedure by talking about the good results they get, even though they don’t have any objective evidence to show that they actually got good results. Some might even consider themselves medical pioneers of sorts. While it’s certainly true that occasionally treatments can be effective before science and clinical guidelines catch up, here’s the thing: the Dartmouth group found no suggestion that the cowboy procedures – those that were adopted before the evidence was there – had any influence on clinical practice guidelines that came along later. It turns out that most of the time, medical “pioneers” aren’t really pioneering anything at all. It’s more like they’re out on a limb that’s not attached to a tree.

Cowboy doctors go it alone, just like the name implies. They have their own rules and beliefs, and aren’t really constrained by the shackles of clinical evidence. They’ll justify a procedure by talking about the good results they get, even though they don’t have any objective evidence to show that they actually got good results. Some might even consider themselves medical pioneers of sorts. While it’s certainly true that occasionally treatments can be effective before science and clinical guidelines catch up, here’s the thing: the Dartmouth group found no suggestion that the cowboy procedures – those that were adopted before the evidence was there – had any influence on clinical practice guidelines that came along later. It turns out that most of the time, medical “pioneers” aren’t really pioneering anything at all. It’s more like they’re out on a limb that’s not attached to a tree.

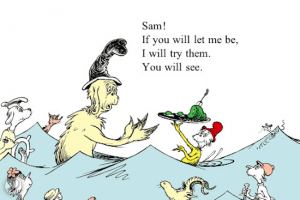

Comforters, on the other hand, drive up costs by doing and trying just about everything. And they usually get credit for doing it, too. But the stark reality is that the outcomes for patients doesn’t really change just because the comforters add more care. Otherwise stated, “Doing everything” might make everyone feel better, but it doesn’t help the condition being treated, and it costs money,

So what makes a cowboy or a comforter?

Veterinarians have a long history of going it on their own. Take me; I’m in solo practice. Individuality is mostly a good thing, I think, but it has it’s limits, for sure. But for a cowboy, it’s more than that. Cowboys usually assert that he or she knows better than the current evidence (interestingly, according to the study, most cowboys are male). But the cold reality is that the Dartmouth researchers could find no evidence at all that these maverick practitioners actually get better results than those who are more conservative, that is, those who are led – and somewhat constrained – by the evidence.

Veterinarians have a long history of going it on their own. Take me; I’m in solo practice. Individuality is mostly a good thing, I think, but it has it’s limits, for sure. But for a cowboy, it’s more than that. Cowboys usually assert that he or she knows better than the current evidence (interestingly, according to the study, most cowboys are male). But the cold reality is that the Dartmouth researchers could find no evidence at all that these maverick practitioners actually get better results than those who are more conservative, that is, those who are led – and somewhat constrained – by the evidence.

Comforters are those that are constantly providing care. Interestingly, comforters are more likely to be women, but they are not likely to also be cowboys. Comforters routinely prescribe more interventions, and more visits, and the costs can add up. People seem to like getting a lot of such attention: but it comes at a cost.

At it’s foundation, these cost issues seem to reflect something of a conflict between those who see themselves as medical artists – caring, or on the “cutting edge” – and those who want to be led by good evidence. Those guided by evidence aren’t quick to adopt practices that aren’t supported by evidence, and they are also quick to drop procedures that are shown not to be effective (count me in the later group). The latter group may not be as appealing on some emotional level, but they are certainly less expensive, and they seem ultimately to get the same results.

At it’s foundation, these cost issues seem to reflect something of a conflict between those who see themselves as medical artists – caring, or on the “cutting edge” – and those who want to be led by good evidence. Those guided by evidence aren’t quick to adopt practices that aren’t supported by evidence, and they are also quick to drop procedures that are shown not to be effective (count me in the later group). The latter group may not be as appealing on some emotional level, but they are certainly less expensive, and they seem ultimately to get the same results.

Is it greed?

Contrary to what you might have heard about “greedy” vets, the Dartmouth group found that very, few few physicians said that they made their decisions based purely on money. They also found that pressure from patients to provide treatments didn’t have a big impact on costs (researchers called the effect “modest”). Decisions are apparently not primarily made because doctors are worried about getting sued, either. Ultimately, the largest degree of variation appears to be explained by differences in a doctor’s beliefs about how well a treatment worked. Just like veterinarians, doctors wildly disagree on that subject, on a variety of therapies. It’s fair to say that there’s a good deal of disagreement among veterinary clients, too.

How might a cowboy drive up veterinary costs?

Well, lots of ways, actually. One way is to do as much stuff as possible, just so that, “No stone is left unturned.” Many people say that they would do anything to help their horse. As a result, there are lots of people that are happy to provide, well, just about anything. So, for example, if a horse has a chronic lameness condition, while a couple of tablets of an anti-inflammatory medication might be just what the horse needs, there are hundreds of possible additional treatments, medications, and supplements. Add in the appeal of something “new,” or “cutting edge,” or, “more aggressive,” and you can end up with a real financial calamity on your hands, with no clear benefits. In human medicine, “cowboy doctors” are associated with a nearly 60 per cent greater spending on health care costs. I can’t imagine that’s not the case in veterinary medicine.

Well, lots of ways, actually. One way is to do as much stuff as possible, just so that, “No stone is left unturned.” Many people say that they would do anything to help their horse. As a result, there are lots of people that are happy to provide, well, just about anything. So, for example, if a horse has a chronic lameness condition, while a couple of tablets of an anti-inflammatory medication might be just what the horse needs, there are hundreds of possible additional treatments, medications, and supplements. Add in the appeal of something “new,” or “cutting edge,” or, “more aggressive,” and you can end up with a real financial calamity on your hands, with no clear benefits. In human medicine, “cowboy doctors” are associated with a nearly 60 per cent greater spending on health care costs. I can’t imagine that’s not the case in veterinary medicine.

“OK, you say, “But don’t I really sort of want a veterinarians who is willing to pull all the stops, even if there’s really very little hope?”

“OK, you say, “But don’t I really sort of want a veterinarians who is willing to pull all the stops, even if there’s really very little hope?”

Well, in my opinion, I’d generally say, “No,” not unless your horse was in some sort of controlled trial, where someone was actually trying to keep track of the results of a new treatment. If a treatment has uncertain benefits, and real costs, I tend not to recommend the treatment. It’s one thing to sell hope based on some medical logic, or realistic expectation of a positive outcome: selling false hope is another thing entirely.

I think that horse owners should be very uncomfortable with cowboys who base their decisions on their intuition, and “good results.” The problem with basing treatments on results is that the people claiming good results usually don’t ever see what happens to horses that don’t get the treatment. All they know is, “After the procedure, the horse got better.” When it comes to comforters, decisions for treating your horse should be more than just because someone is wiling to keep on treating.

Just who are these “cowboys and comforters?”

In my opinion, this is really interesting. In human medicine, they’re more likely to be solo practitioners. There are a lot of solo practitioners in horse medicine – something like 43% of members of the American Association of Equine Practitioners practice by themselves, or with one other person. In human medicine, group practices, or practices with experts with advanced training tend to be more conservative.

In my opinion, this is really interesting. In human medicine, they’re more likely to be solo practitioners. There are a lot of solo practitioners in horse medicine – something like 43% of members of the American Association of Equine Practitioners practice by themselves, or with one other person. In human medicine, group practices, or practices with experts with advanced training tend to be more conservative.

There are also striking regional differences in the cost of human health care. I’d be willing to be that’s the case in horse care, too. Take show horses vs. pleasure horses, for example. In addition, it’s not just that certain areas are more expensive, it’s also that the care provided in certain areas is given to a certain level of expectation: see, for example, show barns, where horses often get myriad treatments to help performance problems, real or imagined.

So what do you do when faced with an expensive choice?

Here are a few suggestions. Before you accept any treatment for your horse, ask the person providing it, “What’s your evidence?” Or get a second opinion before you do something pricey. Or ask the Four Questions that I’ve written about (CLICK HERE). Get involved with your horse’s care – don’t feel pressured to do something just because it’s available, or just because you fell compelled to do “everything possible.”

Here are a few suggestions. Before you accept any treatment for your horse, ask the person providing it, “What’s your evidence?” Or get a second opinion before you do something pricey. Or ask the Four Questions that I’ve written about (CLICK HERE). Get involved with your horse’s care – don’t feel pressured to do something just because it’s available, or just because you fell compelled to do “everything possible.”

The cost of veterinary care is a real issue. There are lots of people at which you can point a finger of blame, if you’re one of those folks that likes do do that. But the bottom line – at least if you believe that there are parallels to veterinary medicine in human medicine – is that there may be any number of people to blame for the cost of your horse’s care, including you. That’s why it’s so important to ask questions before you agree to pay for anything. As much as we may be wowed by cowboys and pleased by comforters, they may just be increasing the cost of your horse’s care, too.