If you have a horse, eventually, you’re going to have to give him some sort of medical treatment. It’s inevitable, like the sun rising. Or taxes. Or the next appearance of the Kardashians in the entertainment headlines. No matter how much you may not want it to happen, you’re going to have to face up to the fact that sometimes, you’re going to have to find somebody to do something to your horse.

If you have a horse, eventually, you’re going to have to give him some sort of medical treatment. It’s inevitable, like the sun rising. Or taxes. Or the next appearance of the Kardashians in the entertainment headlines. No matter how much you may not want it to happen, you’re going to have to face up to the fact that sometimes, you’re going to have to find somebody to do something to your horse.

And the problem is, it puts you in a bad spot.

Anytime you ask help from somebody who knows more about something than you do, you’re kind of at his or her mercy. You have to trust that they’re going to be, oh, say, truthful, ethical, and acting in the best interest of you and your horse (or your dryer, or your car, or whatever else needs some work). Hopefully, everything works out just fine, but the fact of the matter is that sometimes you’ll run into folks who aren’t acting the way that they should, who will use their position as an “expert” to take advantage of the situation.

What should you do? Well, before you let somebody do anything to your horse – before you pay for any diagnostic procedure or treatment – here are four important questions that you should always keep on your mind.

1. Always ask, “Why?” This seems obvious, but even in this modern era, when there’s access to so much information, many horse owners seem to take a lot on faith. You’re calling someone to help you with your horse because you believe that the person is thoughtful and well-informed. I get that. Often, that’s the case. But there may be other considerations.

1. Always ask, “Why?” This seems obvious, but even in this modern era, when there’s access to so much information, many horse owners seem to take a lot on faith. You’re calling someone to help you with your horse because you believe that the person is thoughtful and well-informed. I get that. Often, that’s the case. But there may be other considerations.

Perhaps you’re not aware that person just paid $30,000.00 for a new machine that needs to be used.* Maybe he or she just paid several thousand dollars to get “certified” in something or other. Maybe you read a product in a slick magazine that’s being sponsored by ads from the company selling the product. You really do want to know why a particular treatment or test is being considered; you don’t want to look like a bobblehead doll when it comes to discussing your horse’s health.

Of course, even magazines and people who buy new equipment certainly can provide good information. But you have to be careful about reflex treatment responses, and especially from “specialists” who seem to always find something wrong, busy practitioners who may not have the time (“Take two bute and call me in the morning”), or from people who have products to sell, or “new,” “novel,” or “cutting edge” approaches to promote.

The question “why” is not at all difficult for someone who is really interested in your horse and you (and not just your pocketbook). In fact, “why” questions are easily addressed – and usually welcomed – if a person has taken the time to think over what he or she is doing. If someone isn’t willing to answer the “why” question, can’t answer it to your satisfaction, or gives you some answer that comes from out of left field (“Well, we need to support his energy” or “his rib is out of place” to name only a couple of, well, a whole bunch), there’s reason to be suspicious.

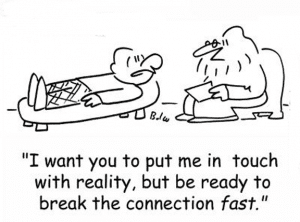

Bottom Line: “Why” questions are necessary reality checks on over-diagnosis and over-treatment.

2. Always ask “What else?” In just about every instance, you have options. The horse that has a bit of swelling over his tendon may not have any swelling or problem in a week, and if it’s a serious injury, the swelling or problem will still be there in a week. One option – surely the cheaper one – besides ultrasound an injections might be to just wait a week.

2. Always ask “What else?” In just about every instance, you have options. The horse that has a bit of swelling over his tendon may not have any swelling or problem in a week, and if it’s a serious injury, the swelling or problem will still be there in a week. One option – surely the cheaper one – besides ultrasound an injections might be to just wait a week.

The “What else?” question is simply a reminder that for most conditions, there are many ways to go. You want the best thing for your horse, but of course, that begs the question of what “Best” means. And here’s your answer:

- The treatment that’s most likely to help

- The treatment that’s least likely to hurt

- The treatment or diagnostic procedure that’s the most economical (assuming that you care about such things).

If you ask someone, “What else,” it should prod that person do do some extra thinking work, and not just do something. It should remind him or her that you want to know all of the options, so that you can comparison shop them: for price, for amount of time, and for outcome. The only option that should really matter is the best one for you and your horse.

If you ask someone, “What else,” it should prod that person do do some extra thinking work, and not just do something. It should remind him or her that you want to know all of the options, so that you can comparison shop them: for price, for amount of time, and for outcome. The only option that should really matter is the best one for you and your horse.

Bottom Line: There are usually a number of ways to go, all of which may get you where you want to go (healthy horse). Make sure you learn about all of them before you pick one of them.

3. Always ask, “What if I Don’t?” Keep in mind that if you decline a test or treatment, the world is unlikely to come to an end, and your horse may get better anyway.

3. Always ask, “What if I Don’t?” Keep in mind that if you decline a test or treatment, the world is unlikely to come to an end, and your horse may get better anyway.

Take example 2, above. Your horse has a tendon injury. What if you don’t do an ultrasound exam? Will the treatment be any different? Will it make a difference in outcome? (NOTE: Ask these same questions before you spring for an MRI for your horse’s lameness). If you need to get your horse back to riding soundness ASAP, perhaps close monitoring will be important. But how about if you’re happy just to give him a year off? Maybe that will do just as well, and for a lot less expense and effort.

On the other hand, if your horse needs colic surgery, and you don’t take him, his life is going to end. Not a good result, for sure, but if you ask the “What if I Don’t” question, you’ll know what will happen if you don’t take him, or if you can’t afford the considerable expense of suffering. Most, importantly, if you know the likely outcome, and you can’t afford the solution, at least you’ll be able to keep him from suffering (which is VERY important).

Bottom Line: “What if I Don’t” questions help you make better decisions, because they help you understand the outcomes without treatment. They may help save you a lot of money, too.

4. Always ask, “Then what?” This is all about knowing what you and your horse might be in for if you do select a treatment.

4. Always ask, “Then what?” This is all about knowing what you and your horse might be in for if you do select a treatment.

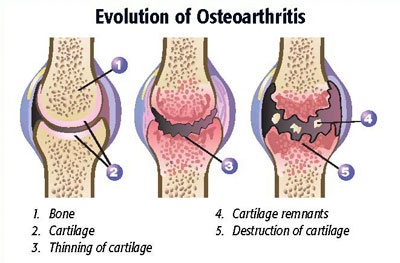

Say you have a horse with osteoarthritis. And you’re thinking about treating him with some injection (there are many). You’d want to know when you’d have to treat him again. You’d want to get some idea of how likely it is that he might respond. how quickly you might see the expected response, or how long he’d be expected to be better (assuming he did get better). You’d want to know if the treatment would change the outcome of the disease, too, or if you’d just be taking care of the clinical signs for a while. And, you might want to ask about the relevance of doing some expensive procedure, say, on an old horse that might do just as well with an inexpensive one (say, giving him some pain relieving medication from time to time vs. giving him shots in the joints or hitching him up to some machine every day).

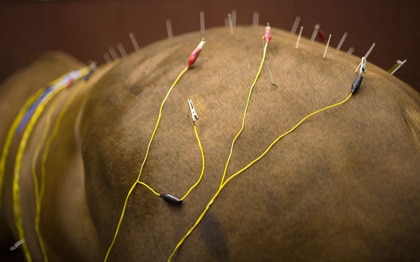

Or say you have a horse with a tendon injury. You’re thinking about getting the tendon injected with PRP, or “stem cells,” or one of any number of new and “cutting edge” therapies. You should ask about how long recovery and rehab is going to take. You should ask for information about other horses that have received the same treatment. You should ask if horses that get the latest therapy actually do better than those that don’t.

Bottom Line: Always try to get some idea of what you’re in for, with or without treatment.

When I look at a horse, it’s not uncommon for my first impression to be right. The horse often has the problem that I thought it had from the start, and for me to also have a pretty good idea of what need to be done. That’s great for your horse, but you need to make sure you understand what’s going on, as well. Don’t just accept what you’re told – ask questions. Get these four questions answered each time you get a recommendation for a procedure or treatment, and each time you consider buying some product. Not only will be you an informed consumer, but you’ll be better able to assess that you’re doing the right thing for you and your horse.

When I look at a horse, it’s not uncommon for my first impression to be right. The horse often has the problem that I thought it had from the start, and for me to also have a pretty good idea of what need to be done. That’s great for your horse, but you need to make sure you understand what’s going on, as well. Don’t just accept what you’re told – ask questions. Get these four questions answered each time you get a recommendation for a procedure or treatment, and each time you consider buying some product. Not only will be you an informed consumer, but you’ll be better able to assess that you’re doing the right thing for you and your horse.

You owe that to both of you, right?

* PLEASE NOTE: I’m not suggesting that veterinarians shouldn’t buy new equipment from time to time. That said, I remember when one of the selling points of digital X-ray machines was that you could take more X-rays more easily.