About three decades ago (as I recall), it was noticed that some Peruvian Paso horses were starting to break down, especially in their hind limbs. As the horses got older their fetlocks began to sink into the ground. Ultimately, the horses became unusable, and many had to be euthanized. The condition was given a name – Degenerative Suspensory Ligament Disease (DSLD) – and a new condition was born.

Since that time, much has been learned about this very curious, and very incurable, condition. What was once thought to be a condition limited to the Peruvian Paso breed, has, in fact, been determined to be a debilitating disorder in several other breeds, including Paso Finos., Peruvian Paso crosses, Arabians, American Saddlebreds, American Quarter Horses, Thoroughbreds, and some European warmbloods.

WHAT IS DSLD?

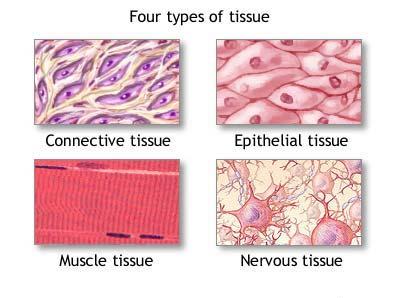

DSLD is a condition that affects the horse’s connective tissue. Connective tissue is tough tissue that connects, supports, binds, or separates other tissues or organs; examples include tendons and ligaments, but also the tough membrane that surrounds muscle cells (and is hard to chew if you find some in your steak). A key feature of DSLD is collagen disruption and the accumulation of substances called proteoglycans between the fibers. In fact, the name “DSLD” is a bit of a misnomer, since the condition doesn’t only affect the suspensory ligament.

DSLD is a condition that affects the horse’s connective tissue. Connective tissue is tough tissue that connects, supports, binds, or separates other tissues or organs; examples include tendons and ligaments, but also the tough membrane that surrounds muscle cells (and is hard to chew if you find some in your steak). A key feature of DSLD is collagen disruption and the accumulation of substances called proteoglycans between the fibers. In fact, the name “DSLD” is a bit of a misnomer, since the condition doesn’t only affect the suspensory ligament.

Proteoglycans are sugar-protein complexes that are normally found between cells. They provide structural support to tissues. A certain amount of proteoglycan turnover is normal to maintain normal tendon/ligament homeostasis – new proteoglycans are made an old ones are replaced. However, in DSLD, there’s just too much of a good thing; the proteoglycans are in excess. This disturbs the normal state of affairs.

It’s not just horses that can be affected with this problem. either. For example, too much proteoglycan accumulation is also seen in tendon aging and tendon disease in humans, particularly Achilles tendinopathy in the human ankle. That’s not much solace, perhaps, but misery does love company.

UNRELATED VERNACULAR ASIDE: Since other structures besides the suspensory ligament can be involved with this condition, it has been proposed that the condition be called Equine Systemic Proteoglycan Accumulation (ESPA) as opposed to DSLD. You can call it ESPA if you want, but most people in the barn won’t know what you’re talking about.

Now, back to the condition.

DIAGNOSIS

savagechickens.com

DSLD is thought to run in families. In certain Peruvian Horse bloodlines or families, DSLD prevalence is up to 40%. The onset of DSLD can be very subtle, but it progresses into a multi-limb lameness over time. As the supporting connective tissues of the limb break down in affected horses, you begin to see additional clinical signs. For example, the fetlocks will start to drop towards the ground, and the pasterns will move towards a more horizontal position. In the hind limb, this also leads to the hocks and stifles straightening out.

Sometimes affected horses have a hard time sanding on one leg when the opposite leg is held up because the additional weight on the one leg causes pain. You can usually feel enlargement and/or hardening of the suspensory ligaments, in the body as well as the branches on either side of the fetlock. The disease is mostly seen in both of the hind limbs, but it can also show up in both of the front limbs, or in all four limbs as well. DSLD is not a condition that is seen only in one limb.

DSLD is slow, and progressive, and causes persistent lameness that’s difficult to relieve. Affected horses are often ultimately euthanized due to breakdown of their limbs – a horse that’s walking on the ground with its fetlocks is heart-breaking to see.

Diagnosis of DSLD is ultimately based on a combination of factors, including family or breed history, physical and lameness examinations of the horse, and ultrasonography of the affected ligament(s). Ultrasound exams show mostly that the suspensory ligament is damaged and that the fibers of the ligament are disrupted with surrounding scar tissue, but ultrasound doesn’t show a specific reason for the problem. In fact, the only way to be sure of a diagnosis of DSLD is to do microscopic examination of the suspensory ligament, with special staining, after the horse has to be put to sleep. It’s frustrating.

People are trying to get to the bottom of it. In 2006, work at the University of Georgia suggested that DSLD was a systemic problem. Based on that, they proposed a biopsy of the large nuchal ligament in the neck as a means of diagnoses, however, the results weren’t consistent, and the test is no longer available. In addition, subsequent work at other labs showed that the problem was more likely to be local rather than systemic. Like I said, it’s frustrating.

Today, the diagnosis of DSLD is typically based on a combination of factors, including family or breed history, physical and lameness examinations of the horse, and ultrasonography of the affected ligament(s). Ultrasound exams show mostly that the suspensory ligament is damaged and that the fibers of the ligament are disrupted with surrounding scar tissue, but ultrasound doesn’t show a specific reason for the problem. In fact, the only way to be sure of a diagnosis of DSLD is to do microscopic examination of the suspensory ligament, with special staining, after the horse has to be put to sleep. It’s frustrating.

More recently researchers have become more interested in the genetic contribution to DSLD, and especially since, 1) DSLD is seen more in certain horse breed families and, 2)It can develop with no history of athletic work or injury to the suspensory ligament. This suggests a genetic contribution, especially in the Peruvian Horse. In the Peruvian Horse approximately 25% of the risk of developing DSLD seems to be genetic (the heritability of DSLD is 0.246 +/- 0.09, if you must know) with the remaining 75% of risk arising from environmental factors. Researchers at Georgia as well as other researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have published their findings. You can the abstracts if you CLICK HERE and HERE but be warned, it’s pretty dense reading. The bottom line is that there is still a lot unclear about the genetic architecture of this condition. More research is still needed not only in the Peruvian Horse but also in other breeds. In addition, some people have proposed a link between DSLD and Equine Cushing’s Disease (PPID), but more research is also needed in this area before we can be sure that there’s a true link.

TREATMENT

Now for the really bad news; there is currently no cure for DSLD. Of course, the lack of a cure should stop absolutely no one from trying to find a cure, and it doesn’t even stop a few people from claiming that they do have a cure. Internet support groups have formed, and various treatments have been proposed, but nothing has really been shown to slow down the condition – and certainly not cure it – in good studies (trust me, if there was anything that really worked to cure a horse of DSLD, everyone would be using it).

The typical treatment for a DSLD horse is based on things that people think that the ought to do, such as “supporting” the limb by means of various shoeing and bandaging techniques, reduction in vigorous exercise and pain relievers, as needed. Interestingly, mild to moderate exercise may have improved signs of mild to moderate DSLD in some horses, at least according to one study (CLICK HERE to see it). Unfortunately, ultimately no treatment has been shown to be effective in stopping progression of the condition (and since you don’t know how the condition will progress in any one horse, it’s hard to say how it might have done without the treatment that you think is working). As with any condition for which there is no proven cure, many novel and unproven therapies, and various supplements, have also been proposed. There’s probably no harm to them but there’s little likelihood of benefit, and the cost of unproven stuff is assured.

The typical treatment for a DSLD horse is based on things that people think that the ought to do, such as “supporting” the limb by means of various shoeing and bandaging techniques, reduction in vigorous exercise and pain relievers, as needed. Interestingly, mild to moderate exercise may have improved signs of mild to moderate DSLD in some horses, at least according to one study (CLICK HERE to see it). Unfortunately, ultimately no treatment has been shown to be effective in stopping progression of the condition (and since you don’t know how the condition will progress in any one horse, it’s hard to say how it might have done without the treatment that you think is working). As with any condition for which there is no proven cure, many novel and unproven therapies, and various supplements, have also been proposed. There’s probably no harm to them but there’s little likelihood of benefit, and the cost of unproven stuff is assured.

Honestly, the best way to deal with DSLD is to try to avoid it. If you’re purchasing a horse from an affected breed, you should certainly have a thorough prepurchase examination performed by a veterinarian. If a potential problem is suspected, it is especially important to evaluate the suspensory ligament with horses with suspected DSLD by ultrasound examination.

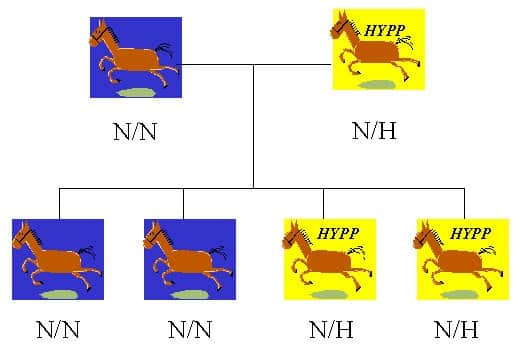

If DSLD is a concern, the ideal test would be a genetic one. Currently most genetic tests for horses screen for simple diseases, meaning that they look for a specific mutations on the horse’s DNA that result in a horse either having a disease or being a carrier for a disease, depending on how the disease is inherited: Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis in Quarter Horses from the “Impressive” line is such a disease. Unfortunately, DSLD is much more complex. Complex diseases result from hundreds to thousands of genetic variants that occur through an animal’s genome; and that’s not even to mention possible environmental risk factors. Until now, genetic testing for complex diseases in the horse has not been feasible.

If DSLD is a concern, the ideal test would be a genetic one. Currently most genetic tests for horses screen for simple diseases, meaning that they look for a specific mutations on the horse’s DNA that result in a horse either having a disease or being a carrier for a disease, depending on how the disease is inherited: Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis in Quarter Horses from the “Impressive” line is such a disease. Unfortunately, DSLD is much more complex. Complex diseases result from hundreds to thousands of genetic variants that occur through an animal’s genome; and that’s not even to mention possible environmental risk factors. Until now, genetic testing for complex diseases in the horse has not been feasible.

Recently the University of Wisconsin-Madison has undertaken genetic testing for DSLD in Peruvian Horses. They compare the DNA of your horse to the DNA of a large reference population of Peruvian Horses. Using this data, this test can predict with approx. 90% accuracy in the Peruvian Horse if a particular Peruvian Horse is at high genetic risk of developing the DSLD condition. This test can be performed on any Peruvian Horse of any age, including foals – CLICK HERE for the link (link:

Once at risk horses are identified a better selection of horse can be made when breeding is considered. Ultimately, selective breeding and identification of affected horses – as has occurred with HYPP – will be needed to help with the reduction of DSLD cases in the horse population.

CONCLUSION

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, when genetic testing becomes validated in all breeds, the routine use of genetic testing for DSLD screening of horses from high-risk breeds should be very valuable in reducing the incidence of the condition. Knowing whether a horse has a high or low genetic risk for developing DSLD would be valuable for selection of horses for breeding, at the time pre-purchase examination, and perhaps for helping develop personalized preventive veterinary care in horses that are at high risk of developing DSLD.

Unfortunately, if your horse does develop DSLD, you’re going to have to do the best you can for as long as you can. For lots more good information about DSLD, you can check out the University of Wisconsin DSLD page if you CLICK HERE