If you’ve been around horses for any length of time (usually measured in minutes), you’ve probably heard that a horse needs X-rays (hopefully, it wasn’t yours). And while you probably have some idea of what X-rays are, I thought it might be fun to talk a bit about them, and to give you some resources so that you have a little bit better idea of what you’re in for when you hear that a horse – or your horse – has had, or needs, X-rays.

A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF X-RAYS

First, a bit of history. X-were discovered way back in 1895. By way of reference, that was the year that Tschaikovsky’s ballet, “Swan Lake” first appeared, the year that volleyball was invented, and the film/camera projector was patented (among many other things – if you want to see what else happened in 1895, CLICK HERE). So we’re talking old technology here. The rays were discovered, somewhat accidentally, by German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Ròntgen (which is why X-rays are called “ròntgen” in German-speaking countries, and in Japan, as well). Ròntgen himself called them “X” rays, the “X” being used because the type of radiation that he discovered was unknown. Over his objections, the name stuck; today, most medical folk call them radiographs, which, when you break it down, means, “writing with radiation.” I think the name X-ray pretty cool, actually – much more mysterious and magical sounding than “radiographs,” don’t you think? The wonderful, mysterious rays pretty much captivated the scientific world, and a mere six months after their discovery, X-rays were being used by battlefield physicians to locate bullets in wounded soldiers. And to top it off, for his discovery, Ròntgen won the very first Nobel prize in physics, back in 1901. If you want to read more about the history of X-rays, or X-rays in general, CLICK HERE.

FUN FACT: By 2010, it was estimated that 5 billion X-ray imaging studies had been conducted around the world. This actually seems rather small to me, since that’s roughly the number of X-rays that some people take during a single prepurchase exam on a modestly priced horse, not to mention the expensive ones.

WHAT ARE X-RAYS?

X-rays are basically the same thing as visible rays of light, it’s just that you just can’t see them. And just like visible light rays, X-rays do one of two things. Either they pass through stuff, or stuff gets in the way of them (in a variety of ways, such as absorption, or reflection, which we’re not going to talk about right now). Pretty simple, actually. So, when you shoot X-rays at a horse, mostly, one of three things can happen:

- Some of the X-rays pass right through the horse

- Some of the X-rays get stopped by tissues in the horse, and especially bone

- Some of the X-rays miss the horse altogether (it’s inevitable).

HOW DO YOU COLLECT AND PLAY WITH THEM?

Of course, shooting X-rays at a horse wouldn’t really do much unless you had something on the other side of the horse to “catch” the X-rays, as it were. For most of my practice life, the “catcher” was a thin piece of film, covered by a material in which little particles of silver were suspended, but not dissolved (the material is called an emulsion). More recently, digital devices came along (as digital devices seem to do) that captured the X-rays with digital X-ray sensors, instead of film. Once digital imaging came along, it pretty much took over the film industry because of all sorts of advantages: you get to see the images immediately, you don’t have to run back to the darkroom and breathe chemicals while standing in a room lit only by a dim red light, you can play with the images, and you don’t need lots of cabinets to store the X-rays. The advantages of digital imaging are also the reason that essentially nobody takes their rolls of film to the drugstore to get their vacation pictures developed anymore, even though, to be fair, you can still get pretty great pictures (and X-rays, for that matter) the old-fashioned way..

Of course, shooting X-rays at a horse wouldn’t really do much unless you had something on the other side of the horse to “catch” the X-rays, as it were. For most of my practice life, the “catcher” was a thin piece of film, covered by a material in which little particles of silver were suspended, but not dissolved (the material is called an emulsion). More recently, digital devices came along (as digital devices seem to do) that captured the X-rays with digital X-ray sensors, instead of film. Once digital imaging came along, it pretty much took over the film industry because of all sorts of advantages: you get to see the images immediately, you don’t have to run back to the darkroom and breathe chemicals while standing in a room lit only by a dim red light, you can play with the images, and you don’t need lots of cabinets to store the X-rays. The advantages of digital imaging are also the reason that essentially nobody takes their rolls of film to the drugstore to get their vacation pictures developed anymore, even though, to be fair, you can still get pretty great pictures (and X-rays, for that matter) the old-fashioned way..

You can play with X-rays even more if you take them from all sorts of angles, and then rely on a computer to assemble the images. That’s what’s involved in a CAT-scan, which, occasionally horses get, too. I say “occasionally” because even though it’s a cool diagnostic technique, and one that can give some interesting information, it’s also one that’s expensive, and requires that the horse gets general anesthesia. For some folks, the risk and expense just isn’t worth it.

You can play with X-rays even more if you take them from all sorts of angles, and then rely on a computer to assemble the images. That’s what’s involved in a CAT-scan, which, occasionally horses get, too. I say “occasionally” because even though it’s a cool diagnostic technique, and one that can give some interesting information, it’s also one that’s expensive, and requires that the horse gets general anesthesia. For some folks, the risk and expense just isn’t worth it.

WHAT DO YOU SEE WHEN YOU X-RAY A HORSE?

Well, here, I’m going to direct you to a couple of fun websites. The University of Illinois School of Veterinary Medicine has a website devoted to imaging anatomy of four different species (including horses, of course), which you can see if you CLICK HERE. On this site, you can take a look at the normal anatomy of various parts of the horse’s front and back legs, and the skull, too. Even if you’re not 100% sure what you’re looking at (veterinary school helps with that, of course), the pictures are really great and you can have all sorts of fun with the color highlighting feature that lights up various bones and bumps and holes.

Kansas State University has another great website, which you can see if you CLICK HERE. Instead of the colorful overlays used on the U of I website, the KSU site uses arrows and legends off to the side to give very nice illustration about the complexity of various joints of the horse’s front and back legs. It’s another great resource for you to scroll around when if you ever find yourself wondering just exactly what the ridge to which the impar ligament attaches to on the navicular bone looks like (hopefully, you won’t find yourself in that situation often).

Kansas State University has another great website, which you can see if you CLICK HERE. Instead of the colorful overlays used on the U of I website, the KSU site uses arrows and legends off to the side to give very nice illustration about the complexity of various joints of the horse’s front and back legs. It’s another great resource for you to scroll around when if you ever find yourself wondering just exactly what the ridge to which the impar ligament attaches to on the navicular bone looks like (hopefully, you won’t find yourself in that situation often).

DO X-RAYS HAVE ANY LIMITATIONS?

Yes, well, here’s where things can get a little sticky, diagnostically speaking. Remember how X-rays work, that some x-rays get stopped by tissues, and others pass through? It turns out that the tissues that are especially good at stopping X-rays are bone. Bone is very dense, it has a lot of minerals in it (especially calcium and phosphorus), and when X-rays hit bone, most of them run out of steam. That means that there’s very little X-ray to pass on  through to the sensor (film or digital). As a result, what you see on the image is white (or whitish, anyway). On the other hand, air stops no X-ray at all, and when X-rays pass through the air and hit the sensor, what you see on the image is black. Pretty simple, actually.

through to the sensor (film or digital). As a result, what you see on the image is white (or whitish, anyway). On the other hand, air stops no X-ray at all, and when X-rays pass through the air and hit the sensor, what you see on the image is black. Pretty simple, actually.

Limitation #1 – The problem is that, just like the air, most of the non-bone tissues of the horse (which are mostly composed of water) don’t stop many X-rays, either. Things like tendons and ligaments and blood vessels end up looking pretty black, too. That’s why, for example, when your horse has a tendon injury, if you want to see what’s going on, you use a different imaging technique, such as ultrasound.

Take Home Message #1 – If you want to look at bone, X-rays are a pretty good choice. If you want to look at something else, use something else.

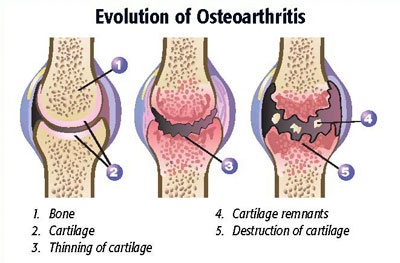

Limitation #2 – X-rays are not all that sensitive. Here’s what I mean. When you’re talking about a medical test, “sensitivity” is the ability of a test to correctly identify those with the disease that you’re looking for. And here, X-rays have some pretty serious limitations. Take disease of the navicular bone (please). We know now with absolute certainty that X-rays of the navicular bone are not diagnostic for disease of the navicular bone. It’s that way in other species, too. For example, in people, it’s well known that X-rays don’t correlate very well with knee pain (CLICK HERE if you want to see a study). Otherwise stated, people with some rather ugly X-rays of their knee can show very little in the way of clinical signs of arthritis, especially pain, and people who are in a lot of pain can have X-rays that don’t look very bad at all.

Limitation #2 – X-rays are not all that sensitive. Here’s what I mean. When you’re talking about a medical test, “sensitivity” is the ability of a test to correctly identify those with the disease that you’re looking for. And here, X-rays have some pretty serious limitations. Take disease of the navicular bone (please). We know now with absolute certainty that X-rays of the navicular bone are not diagnostic for disease of the navicular bone. It’s that way in other species, too. For example, in people, it’s well known that X-rays don’t correlate very well with knee pain (CLICK HERE if you want to see a study). Otherwise stated, people with some rather ugly X-rays of their knee can show very little in the way of clinical signs of arthritis, especially pain, and people who are in a lot of pain can have X-rays that don’t look very bad at all.

I suspect it’s the same way in horses. Other than studies about the horse’s navicular bone – a real can of worms, as it turns out – there aren’t very many studies that have looked at the correlation between X-ray findings and clinical lameness. I did one way back in 1997 (CLICK HERE) – in fact, all of the horses that I looked at in my flexion test study were sound, even though some of them had some X-rays that were remarkably different from what we would consider normal. And in my clinical practice, I routinely find some pretty odd looking X-rays on some very sound horses.

Take Home Message #2 – You have to be very careful not to overinterpret what you’re seeing on X-rays. If your horse is sound, and maybe he has a funny looking X-ray, don’t tell him.

Take Home Message #2 – You have to be very careful not to overinterpret what you’re seeing on X-rays. If your horse is sound, and maybe he has a funny looking X-ray, don’t tell him.

Limitation #3 – X-rays simply can’t predict the future. That’s something to keep in mind when you’re buying a horse. Lots of people spend lots of money on X-rays in hopes that they’ll be able to get some idea how horses are going to do in the future. On the other hand, lots of people lose lots of money because people offer less than the asking sales price because of supposed X-ray “changes” that actually have no known significance (think back X-rays, or navicular bone X-rays, to name a couple). X-rays can’t tell you how fast a known problem will get worse and they also can’t tell you if a “change” is going to develop into something significant in a horse that is currently sound.

Take Home Message #3 – You have to ride the horse; you can’t ride the X-ray.

X-rays are an extremely useful imaging tool in horse medicine, especially if you’re doing lameness work (which, as a horse veterinarian, you often are). But you have to be a bit careful in interpreting them, because not every “change” is significant, and we don’t always know what those changes mean; they may even be normal for a particular horse. If your veterinarian finds something on your horse’s X-ray, it’s often a good idea to get a second opinion before making an important decision: consider having them sent to a veterinary radiologist. X-rays are old technology – and very useful technology, for sure – but you have to remember to consider them in the mysterious light of the horse.