A reader comment inspired me to write about red flags could tip you off to the fact that a therapy (any therapy) might not be all it’s cracked up to be. I get asked this question a lot, pretty much under the guise of, “Well, it’s all great that you have all of this education, and you read journals, but how the heck are we supposed to know if something really works or not?”

A reader comment inspired me to write about red flags could tip you off to the fact that a therapy (any therapy) might not be all it’s cracked up to be. I get asked this question a lot, pretty much under the guise of, “Well, it’s all great that you have all of this education, and you read journals, but how the heck are we supposed to know if something really works or not?”

Frankly, I think it’s a great question. Horse owners are swimming in a sea of misinformation that’s stocked with products and services that are unlikely to do any good for your horse. If you’re fishing for something to help your horse, how do you know what to keep and what to throw back?

Frankly, I think it’s a great question. Horse owners are swimming in a sea of misinformation that’s stocked with products and services that are unlikely to do any good for your horse. If you’re fishing for something to help your horse, how do you know what to keep and what to throw back?

So, without further ado, here are 14 tips. (There’s a lot of BS out there – apparently, there’s a need for a lot of tips.)

1. The product is mostly supported by testimonials. Testimonials are great advertising. Apparently, for some reason, men may want to wear the same brand of underwear as does Michael Jordan, even if they aren’t 6′ 6″ ex-basketball players. Jim Palmer, the former Baltimore Orioles pitcher, had a great body, and apparently sold a lot of underwear because women thought he was cute, and wanted their men to look just like Jim (which, honestly, was probably a bit of a stretch most of the time). Of course, none of this had anything to do with how the underwear actually fit – but hey, in some way, you could be like them.

Testimonial evidence should be, in general, unpersuasive when it comes to claims for medicines, machines, or products. For example, a device that advertised, “Leading veterinarians agree…” would not normally be considered scientifically credible, unless the leading veterinarians and their supporting data were identified. And, honestly, it shouldn’t really matter how handsome the rider or trainer is, or what particular event that they just won – they won the event by a combination of good luck, good horsemanship, and a good horse, not due to any product or treatment.

2. Vague, unsupported claims of effectiveness. You see this sort of thing all the time when it comes to crazy supplement claims. I mean, what the heck does “improving bloom” mean? Is your horse aspiring to become a flower or something? A product or service should state exactly what it does, say how it does it, and provide the evidence to support the claim. And, if it doesn’t, you can probably save yourself time and money if you pass it by. If they say, “We don’t know how it works,” it probably doesn’t.

3. Misuse of defined scientific terminology. Mostly, this is the advertising equivalent of the old saw, “If you can dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with BS.” For example, you sometimes hear people talking about quantum theory to explain weird treatments (like homeopathy). Quantum physics is kind of weird – homeopathy is really weird – so they must have something in common, right? (WRONG). Similarly, treatments that “detoxify” the body, or “support” the kidneys should be viewed with skepticism, unless such terms and their mechanisms of action were defined. They made and advertised such products 100+ years ago; the terms don’t mean anything more now than they did then.

3. Misuse of defined scientific terminology. Mostly, this is the advertising equivalent of the old saw, “If you can dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with BS.” For example, you sometimes hear people talking about quantum theory to explain weird treatments (like homeopathy). Quantum physics is kind of weird – homeopathy is really weird – so they must have something in common, right? (WRONG). Similarly, treatments that “detoxify” the body, or “support” the kidneys should be viewed with skepticism, unless such terms and their mechanisms of action were defined. They made and advertised such products 100+ years ago; the terms don’t mean anything more now than they did then.

4. Mischaracterization of medicine. I think it is particularly telling when a therapy tries to distinguish itself from science and medicine. What, exactly, is wrong with good medicine? Isn’t that what people want for their horses? For example, a seller of a particular product might warn about the side effects of taking “too many pills,” and offer their product as an “alternative;” it may be an alternative, at least in the sense that it’s something else that you could do, but, at the same time, why use it if there’s no evidence that the product actually works?

It’s the same thing when people talk about “types” of medicine. Sure, they practiced medicine in the east, and in the west, but, fundamentally, they were all trying to do the same thing: fix their patients. Similarly, the idea that “western” medicine is only trying to treat disease – but other approaches are into prevention or “holism” or whatever – is just wrong.

Remember this: good medicine is good medicine. It either works, or it doesn’t.

5. Virtues without vices. If a something works, it works because it does something. If it really does something – if it causes some change in the horse’s body – there’s always the potential for something to go wrong. So, for example, if a treatment is advocated a treatment as “natural” or “holistic” or “free of side effects,” who cares? Such statements mean nothing unless there’s evidence that the treatment is effective. And, of course, “natural” substances are certainly not free of risk (e.g., rattlesnake venom, poison ivy, etc., etc.). Any treatment that has effects also has side effects; conversely, a treatment free of side effects probably doesn’t have have any effects at all.

6. False and inaccurate claims. If a statement is made that is contrary to fact, it’s usually an indication that a theory or therapy is not likely to be clinically useful. For example, many therapies, such as magnets, (but also many others), have stated that they increase blood flow, which, by implication, is good. They don’t, and, often, it isn’t, at least not necessarily. There’s only so much blood to go around, and the flow of blood is tightly controlled by the body. Furthermore, extra blood isn’t necessarily a good thing; several disease conditions are characterized by an overgrowth of blood vessels.

6. False and inaccurate claims. If a statement is made that is contrary to fact, it’s usually an indication that a theory or therapy is not likely to be clinically useful. For example, many therapies, such as magnets, (but also many others), have stated that they increase blood flow, which, by implication, is good. They don’t, and, often, it isn’t, at least not necessarily. There’s only so much blood to go around, and the flow of blood is tightly controlled by the body. Furthermore, extra blood isn’t necessarily a good thing; several disease conditions are characterized by an overgrowth of blood vessels.

Other facts –

a. Nothing can return injured cartilage back to normal

b. Nothing has been shown to prevent arthritis

c. Nothing has been shown to prevent colic

d. Nothing can cause hair to grow in scarred areas of skin

7. Too good to be true. If you see unlikely claims that you – or anyone – should have known about, don’t bother with them. Everyone would use a cure that really worked, and, assuming you’re not living under a rock, you’d know, too, if there were suddenly a solution to a problem that couldn’t have previously been solved. I mean, if something cured arthritis, do you think it would be a secret, or that they’d restrict it to horses? If it sounds too good to be true, don’t bother with it.

8. Reliance on subjective measurements. Subjectivity is notorious for introducing error into results. If you’re trying to assess whether a horse feels better, there’s a lot more room for error than when you’re measuring a response on a blood test. Objective measurements are ideal. Even though there are times when studies must rely on measurements of subjective experience, the studies have to be tightly controlled to get good results. If a product is claiming “feel good” results instead of providing measured data, be worried that it’s not really doing anything at all.

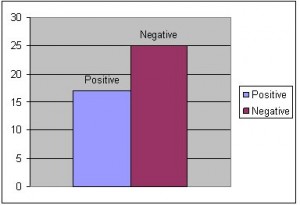

9. Ignoring negative results. Negative results count more against a claim than positive results count for it. This is especially true if negative results continue over time, or it studies keep coming up on both sides of the “Does it work?” question. Glucosamine and chondroitin are like that: for 40-some years. If phenomena are real, those studying it should eventually reach the point where they, and eventually, others, can reliably demonstrate it. If people keep talking about needing more studies, wait for them.

10. Lack of direct evidence. It’s OK to have a theory about how something works. But theories should allow themselves to be tested fairly directly. If the promoters of a therapy can’t show you how something works – if it’s only a theory – it’s not a bad idea to wait. Sure, something can work without knowing how it works, but in this day and age, that’s pretty uncommon.

11. No deepening evidence. Over time, if a clinical effect is useful and relevant, it will become obvious and repeatable. As experimental and theoretical work progresses, more and more sound evidence should appear, and it should appear fairly quickly.

11. No deepening evidence. Over time, if a clinical effect is useful and relevant, it will become obvious and repeatable. As experimental and theoretical work progresses, more and more sound evidence should appear, and it should appear fairly quickly.

So, for example, in spite of hundreds of years of experience and decades of investigation, the “state of the art” in most “alternative” therapies appears to have advanced little from the times in which those therapies were initially proposed. It’s the same way with a lot of joint therapies – many have been around for decades, and they still haven’t been shown to do much (if anything). Personally, I wouldn’t hold my breath, if, after several decades, people are still talking about the “promise” of a therapy.

12. Poor investigation of alternative explanations. Results claimed for some therapies are often easily explained. People who claim that acupuncture works (not me) may say that acupuncture causes rises in endorphins, a pain killer that’s in the body. But when it comes to getting endorphins up in horses, a good ride the trailer will do just fine. In fact, the horse’s “natural” opiate levels rise with just about anything that’s stressful. Alternative explanations need to be ruled out before theories are accepted.

13. Paradigm talk. A paradigm is a philosophical and theoretical framework within which theories, laws, and generalizations and even experiments are formulated. So, you get phrases like, “Western medicine,” and “traditional” medicine, and “eastern” medicine, and “natural” medicine, and so forth. But medicine doesn’t work because of someone’s philosophical approach (placebos do, but that’s another discussion). If a therapy is effective, there’s no need for a paradigm shift – it’ll just work!

14. Mealy-mouthed excuses. When there is little evidence to support a belief, proponents of such beliefs tend to offer excuses. Such excuses range from a “lack of funding” to “the medical establishment does not want our therapy to be known.” There would be no reason for such excuses if there were good evidence for the beliefs in question. The fact that such excuses are offered is a virtual admission that there is not good evidence to support the beliefs.

14. Mealy-mouthed excuses. When there is little evidence to support a belief, proponents of such beliefs tend to offer excuses. Such excuses range from a “lack of funding” to “the medical establishment does not want our therapy to be known.” There would be no reason for such excuses if there were good evidence for the beliefs in question. The fact that such excuses are offered is a virtual admission that there is not good evidence to support the beliefs.

Honestly, when it comes to product and services for horses, it’s a jungle out there. There’s no real oversight for the things that people will try to sell you. People can and do make false claims with impunity.

Be careful about jumping on the next therapeutic bandwagon that comes down the pipe, at least if little things like money are important to you. If you think your horse has a problem, about the only thing that you can be sure of is that there will be someone there to trying to sell you something to fix it. Be smart, and don’t get sucked in to buying products or services for your horse that don’t do anything. Look for clues that they might not really work after all.