If you’ve had a horse for any period of time, chances are that he’s had an episode of lameness (hopefully, it was brief). And, if he’s had an episode of lameness, there’s a decent chance that he may have had an injection into one or more of his joints. When that situation occurs with me, one of the questions that I’m most frequently asked is, “How long will the injection last?” Good question, really.

If you’ve had a horse for any period of time, chances are that he’s had an episode of lameness (hopefully, it was brief). And, if he’s had an episode of lameness, there’s a decent chance that he may have had an injection into one or more of his joints. When that situation occurs with me, one of the questions that I’m most frequently asked is, “How long will the injection last?” Good question, really.

And, to be honest, many times I’m not really sure what to say.

Really, when it comes to joint injections, there are two sort of different conditions that usually get treated. One is acute (acute = happened recently) arthritis (joint inflammation), you know, the kind you get when you mildly sprain your ankle or twist your knee (without doing any other kind of damage to ligaments and such).

The nice thing about acute arthritis is is that it tends to get better almost no matter what you do, you know, kind of like when you mildly sprain your ankle or twist your knee. As long as you let things get better and don’t go jumping, or piaffing, or spinning, or whatever, too soon, if a joint gets acutely inflamed, everything is probably going to be just fine. And he’ll most likely be fine without any residual problems, either. In such cases, a joint injection can help quiet down the inflammation – how much it’s needed is another question, of course – but that’s probably not a bad thing. With acute arthritis, things usually work out pretty well.

The nice thing about acute arthritis is is that it tends to get better almost no matter what you do, you know, kind of like when you mildly sprain your ankle or twist your knee. As long as you let things get better and don’t go jumping, or piaffing, or spinning, or whatever, too soon, if a joint gets acutely inflamed, everything is probably going to be just fine. And he’ll most likely be fine without any residual problems, either. In such cases, a joint injection can help quiet down the inflammation – how much it’s needed is another question, of course – but that’s probably not a bad thing. With acute arthritis, things usually work out pretty well.

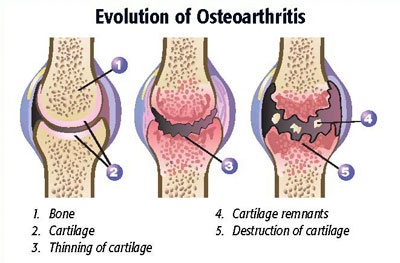

Osteoarthritis is a different kettle of fish. Osteoarthritis involves bone (the “osteo-” part), and it’s generally chronic, that is, it’s a problem that’s been developing over a period of time. Without getting into all of the anatomy and such, the fundamental problem with osteoarthritis – and please keep this in mind – is you can’t cure it. And that’s a problem.

NOTE: In medicine, the number 1 ideal thing to do with any problem is to be able to help cure it. Get rid of it. Forever. If the problem is gone, the clinical signs (of which limping is the big one) go away. And everyone is happy.

With osteoarthritis, that “cure” option isn’t available. That means that nothing works. And it also means that people will try just about anything

NOTE NUMBER TWO: Here’s another Ramey Rule. The more treatments that there are for a particular condition, the less likely it is that any one of them really does much. If there’s a likely cure for a condition, everybody knows about it, and uses it. If there are dozens of treatments, it’s likely that none of them are really effective. And with osteoarthritis, well, there are magnets, and supplements, and special shoeing, and injections in the muscle, and injections in the vein, and liniments, and electrical stimulators, and, stem cells, and platelet rich plasma, and IRAP®, and I could keep going but I think you get my point. At best they might give some temporary relief, but they are certainly not going to cure the problem.

Oh, and joint injections – the subject of this article.

In February 2015, a study came out looking at how long you can expect an effect from joint injections. And it’s absolutely fascinating. So here goes.

While there are lots of things that veterinarians inject into horse joints, probably the most common involves the injection of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents that have been studied a lot, and suffice it to say that they do help relieve pain and inflammation in an inflamed joint (although there are lots of other questions). It’s also not uncommon that a corticosteroid will get combined with hyaluronate (also known as hyalruonic acid, or HA) in an effort to increase the effect. HA is thought to function as an anti-inflammatory agents, as well as something of a joint lubricant, although the evidence supporting its use is much less robust than is the evidence for corticosteroids. Alone or in combination, both medications have been used for decades by veterinarians treating joint inflammation (both acute, and osteoarthritis). Curiously, however, until this study, nobody had every actually looked to see if the combination is better than just injecting corticosteroids by themselves. And nobody had really looked to see how long either combination helped: if they helped at all.

While there are lots of things that veterinarians inject into horse joints, probably the most common involves the injection of corticosteroids. Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory agents that have been studied a lot, and suffice it to say that they do help relieve pain and inflammation in an inflamed joint (although there are lots of other questions). It’s also not uncommon that a corticosteroid will get combined with hyaluronate (also known as hyalruonic acid, or HA) in an effort to increase the effect. HA is thought to function as an anti-inflammatory agents, as well as something of a joint lubricant, although the evidence supporting its use is much less robust than is the evidence for corticosteroids. Alone or in combination, both medications have been used for decades by veterinarians treating joint inflammation (both acute, and osteoarthritis). Curiously, however, until this study, nobody had every actually looked to see if the combination is better than just injecting corticosteroids by themselves. And nobody had really looked to see how long either combination helped: if they helped at all.

This study was a real group effort. It involved 80 horses owned by clients – this wasn’t an experimental study, which, in my opinion, makes it especially interesting – and 13 veterinary clinics participated in the study. The group looked at how well one commonly used steroid, triamcinolone (TA), worked, compared to TA + HA (if you didn’t know, it’s almost mandatory to use abbreviations when you’re writing a scientific paper). The investigators kept track of lameness and joint swelling, and they checked with owners and referring veterinarians all the way out to three months after the horses were injected. And what they looked for was the clinical success rate, that is, they wanted to see how well the treatments worked (and they did all sorts of complicated statistical analysis, too, which is one of those things that’s very important, but almost mind-numbing if you’re not into it).

So what did they find? Well, they found that three weeks after treatment, 87.8% of the horses that got TA only were better, while only 64.1% of the horses that got the TA + HA combination were better. They also found – kind of to nobody’s surprise, actually – that the older the horses were, the less likely treatment was to be successful. Horses over 13 years of age had a reduced success rate for the combination treatment. And here’s the kicker – three months after treatment, just half the horses in each group had returned to their previous level of performance.

So what did they find? Well, they found that three weeks after treatment, 87.8% of the horses that got TA only were better, while only 64.1% of the horses that got the TA + HA combination were better. They also found – kind of to nobody’s surprise, actually – that the older the horses were, the less likely treatment was to be successful. Horses over 13 years of age had a reduced success rate for the combination treatment. And here’s the kicker – three months after treatment, just half the horses in each group had returned to their previous level of performance.

Oh, I almost forgot. You can CLICK HERE to read the whole study.

It’s not the results of this study are completely unexpected. A study done on 51 horses with osteoarthritis of the lower joints of the hock found that 58% of the horses improved initially, but that 90% of them had relapsed by about 56 days later (CLICK HERE to read it). HA alone certainly seems not to do the trick – a study of injections into the joint of the foot (the coffin joint, so named because, according to an 18th century text, it is contained within the hoof “as if within a coffin”) found that only 30% responded to injections that only contained HA (CLICK HERE).

It’s pretty interesting that so many horses responded to treatment at three weeks. I mean, almost 90% of the horses were much better three weeks after they were examined. That’s a lot of success. But it may not all be due to the joint injections. You see, after the injections, horses were rested and walked for three weeks before they were re-evaluated. I’m sure that you can pretty easily figure out that rest and reduced work helps just about anything that’s sore, and rest alone has been shown to help horses with joint problems in other studies.

It’s pretty interesting that so many horses responded to treatment at three weeks. I mean, almost 90% of the horses were much better three weeks after they were examined. That’s a lot of success. But it may not all be due to the joint injections. You see, after the injections, horses were rested and walked for three weeks before they were re-evaluated. I’m sure that you can pretty easily figure out that rest and reduced work helps just about anything that’s sore, and rest alone has been shown to help horses with joint problems in other studies.

Was this a perfect study? In a word, “No,” but to be honest, you can find faults with a lot of studies. However, the weaknesses of the study are at least partially overcome by the fact that 13 different clinics were involved (which overcomes problems that occur when only one person is looking at a study), and that 80 horses were used (which, compared to many horse studies, is a pretty good number). Of course, it would have been nice to see how things were going 6 or 12 months down the road, but if only half of the horses were better at 3 months, you wouldn’t expect the number to increase as time went by.

So, what’s to be made of all this? Well, it’s sort of a reality check. Here’s what I take away from it.

- Even though it makes some theoretical sense to use the drugs together, the TA + HA horses actually didn’t fare as well as the TA only horses when they were checked three weeks after injection.

Otherwise stated, HA didn’t hurt the horses, but it didn’t help. And this is particularly annoying, because you’d think that the combination might be beneficial: honestly, just about everyone thinks that. There are even a couple of small studies that support the idea that the combination is better. But a real tragedy of science is when the beautiful damsel of theory gets slain by the ugly dragon of reality.

Otherwise stated, HA didn’t hurt the horses, but it didn’t help. And this is particularly annoying, because you’d think that the combination might be beneficial: honestly, just about everyone thinks that. There are even a couple of small studies that support the idea that the combination is better. But a real tragedy of science is when the beautiful damsel of theory gets slain by the ugly dragon of reality.- Nobody really knows why the combination didn’t appear to work as well.

- At three months, only half the horses were back to their previous level of work, even though the initial response was actually pretty remarkable (although there could have been other reasons for that).

- Corticosteroids in the joint are potent anti-inflammatory agents, but their effects don’t last all that long (three months or less).

- There doesn’t seem to be much reason to add the expense of HA to a horse’s joint when a horse is being treated for osteoarthritis.

- The older a horse is, the less likely it’s going to respond to treatment. Or, as my Dad once noted, getting old isn’t for sissies.

If your horse has osteoarthrtiis, don’t expect a joint injection to be a long term solution. If your horse gets a few months of relief, that’s probably about what you can expect (and if he’s permanently better after a joint injection, he most likely didn’t have osteoarthritis). And combining treatments isn’t necessarily better, in spite of the fact that it makes some sense, and it’s commonly done. In fact, with rest, and/or a lighter, more regular work load, and/or the ability to move around all the time, and/or maybe a little bit of anti-inflammatory/pain relieving medication, things might get a good bit better for your horse’s joint without any injection-type intervention at all.

If your horse has osteoarthrtiis, don’t expect a joint injection to be a long term solution. If your horse gets a few months of relief, that’s probably about what you can expect (and if he’s permanently better after a joint injection, he most likely didn’t have osteoarthritis). And combining treatments isn’t necessarily better, in spite of the fact that it makes some sense, and it’s commonly done. In fact, with rest, and/or a lighter, more regular work load, and/or the ability to move around all the time, and/or maybe a little bit of anti-inflammatory/pain relieving medication, things might get a good bit better for your horse’s joint without any injection-type intervention at all.

PS – What about all of the other stuff that can be injected in horse joints? Gotta have material for future articles!