The mule may not be so liable to spavin as the horse, but he has ringbone just the same. “The Mule” by Harvey Riley, 1867

The mule may not be so liable to spavin as the horse, but he has ringbone just the same. “The Mule” by Harvey Riley, 1867

One of the fun things about horse medicine is that it has a lot of living history attached to it. Take “ringbone” (please). According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first mention of ringbone (hyrngban) is from Old English, c. 1000 AD. I point this out to say that this condition has been plaguing horses for a long time and it doesn’t look like it’s going to be letting up any time soon. So, since it’s a problem that’s likely to be with us for a while longer, let’s look at quick this not uncommon problem of mostly older horses with a clear set of eyes, so you can try to help your horse and also afford your rent or mortgage payment.

WHAT IS RINGBONE?

A ryngbone is an yll soraunce and appereth before on the foote. Fitzherb, 1523

Ringbone is a colorfully-named variation of arthritis, or, more specifically, osteoarthritis. The “osteo” part means “bone,” the “-arth” part means “joint,” and the “-itis” part means “inflammation,” so, put them all together and you’ve got inflammation of bone and joint.

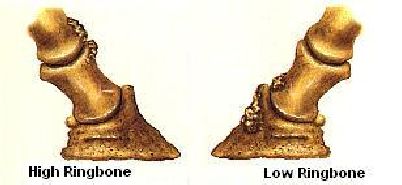

That, unfortunately, is just the start of things. You see, inflammation is an insidious, incessant problem that erodes the normal joint structures: particularly cartilage and bone. It feeds on itself, too – the worse things get, the worse things get. In more severe cases, bone builds up around one or both of the joints in the horse’s pastern area: the “ring” in ringbone, as it were.

Depending on which joint gets involved, the ringbone may be described as “low” or “high,” but fundamentally the process is the same. The more the joint is inflamed the more destruction occurs; as the process goes on, pain and inflammation increase, as well. Ringbone, as well as all other places where osteoarthritis occurs, inevitably gets worse over time.

A spavin was apparent in one leg, while on another was a great ringbone. “The Boys of Old Monmouth” by Everett T. Tomlinson, 1898

WHAT CAUSES RINGBONE?

He was very aged; his teeth, almost gone; and his limbs, once so nimble, now covered with warts and ringbones. “Minnie’s Pet Dog” by Madeline Leslie, Late 19th century

Sometimes you know what causes ringbone – sometimes you don’t. For example, a horse with a fracture into his pastern joint will inevitably get ringbone because of the inflammation and instability that fractures cause in joints. Infection in a joint can end up causing osteoarthritis. We know about those causes.

Sometimes you know what causes ringbone – sometimes you don’t. For example, a horse with a fracture into his pastern joint will inevitably get ringbone because of the inflammation and instability that fractures cause in joints. Infection in a joint can end up causing osteoarthritis. We know about those causes.

Other thoughts about causes of ringbone are just speculation. It’s easy to surmise that “improper” shoeing might result in stress on a joint that results in osteoarthritis, but there’s no such thing as a single “proper” way to shoe any horse (although it does seem like the person coming after the other person who previously shod the horse always opines that the previous person’s way of trimming was improper). The same with conformation – we can surmise that a horse with legs that are less than our most recently determined ideal might have stresses on them that result in arthritis, but, in fact, we can’t pick out which crooked legged horse is going to get arthritis in advance. It’s easy to say that old age “causes” ringbone but not all old horses get ringbone (or any other variation of arthritis). Otherwise stated, osteoarthritis is not an inevitable consequence of aging.

The one thing that we do know is that by the time you see ringbone in a joint, the horse has already left the barn, the cat is already out of the bag, or whatever other metaphor indicating that things are too late you want to use. From that point on, your focus has to be on trying to help your horse deal with the problem. It’s never going back to normal, no matter what you do.

HOW DO YOU TREAT RINGBONE?

TREATMENT: If the Ringbone is very much inflamed, reduce the heat by applying cold water or ice packs to the part. “The Veterinarian” by Chas. J. Korinek, Jan 1915

In a sense, you can’t treat ringbone. That is, there’s no therapy – no shot, no powder, no supplement, and no pill – to stop the progression of the disease.

Since the process can’t be stopped, all of the therapies available try to try to help the horse deal with his problem. There are lots of choices – pain relievers and anti-inflammatories, magnets and lasers, liniments and poultices, acupuncture and injections, manipulations and healing with hands, and supplements and DMSO, and on and on and on. While some may assert that they can “support” your horse or “help” this, that, or the other, the thing that these products all have in common is that none of them – none of them – stop the progression of the disease.

Since the process can’t be stopped, all of the therapies available try to try to help the horse deal with his problem. There are lots of choices – pain relievers and anti-inflammatories, magnets and lasers, liniments and poultices, acupuncture and injections, manipulations and healing with hands, and supplements and DMSO, and on and on and on. While some may assert that they can “support” your horse or “help” this, that, or the other, the thing that these products all have in common is that none of them – none of them – stop the progression of the disease.

In addition, very few have them have been shown to really do much of anything at all.

That’s not to say you should throw up your hands and do nothing for a horse with ringbone. It’s just that you have to understand that you’re goal in dealing with ringbone (and any other kind of osteoarthritis) is to try to control the clinical signs of the disease since you can’t really control the ringbone.

MEDICINES, AND SUCH

Medicines for ringbone focus on trying to control or cover up pain and inflammation. You can do that, to a certain extent, but that extent largely depends on two things:

Medicines for ringbone focus on trying to control or cover up pain and inflammation. You can do that, to a certain extent, but that extent largely depends on two things:

- How bad the problem is

- How much exercise is required of the horse

Looking at it in this way, you might reasonably surmise that the probability of an international level dressage horse with advanced ringbone competing in the Olympics will be much less than the probability of an old pleasure horse with advanced ringbone taking a walk on the trail once on the weekends. The worse the problem is, and the more that the horse is asked to do, the more likely the horse will have difficulties dealing with it.

The two most commonly used medications are probably non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as phenybutazone, flunixin meguline, firocoxib, or others) and steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as methylprednisolone or triamcinolone. NSAID’s are generally given systemically (orally, IV, and such): there’s also one that you can rub on top of the arthritic joint. Corticosteroids are most commonly injected directly into joints. NSAIDs directly relieve both pain and inflammation; corticosteroids relieve inflammation directly, and, if the inflammation is reduced, so is pain (indirectly).

Of course, NSAIDs and corticosteroids are by no means the only substances prescribed for ringbone. However, this is where things get both less evidence-based and more expensive. You’ve got all sorts of “cutting edge” products to inject into joints, muscles, and veins, some of which are very commonly prescribed – and even more heavily advertised – but actually have surprisingly little scientific data to support their use: the list is long. Ditto joint supplements. Based on my experience, as well as that of my clients, I generally don’t bother with them. Things that you rub on sore joints, such as liniments and DMSO and various other substances may cause a feeling of warmth in the area but they don’t do anything to affect the underlying disease.

Of course, NSAIDs and corticosteroids are by no means the only substances prescribed for ringbone. However, this is where things get both less evidence-based and more expensive. You’ve got all sorts of “cutting edge” products to inject into joints, muscles, and veins, some of which are very commonly prescribed – and even more heavily advertised – but actually have surprisingly little scientific data to support their use: the list is long. Ditto joint supplements. Based on my experience, as well as that of my clients, I generally don’t bother with them. Things that you rub on sore joints, such as liniments and DMSO and various other substances may cause a feeling of warmth in the area but they don’t do anything to affect the underlying disease.

AN IMPORTANT NOTE: One thing that you can do is to let your horse move around as much as possible. Gentle, regular movement helps keep joints from getting stiff – you’ve probably discovered that yourself if you’ve been around for a while.

The problem for horse owners is that, with so many choices, you can go broke trying them all. I’d recommend you ask to see the evidence behind them before you just go chasing after a therapy that you already know is not going to fix the problem anyway.

SHOEING

The ringbone is a certain superfluous grissle, growing about the coronet of the horses hooofe. Markam, 1617

Of course, horses get shod to try to help them move or to protect their feet, so it should be no surprise that there are all sorts of shoeing and trimming suggestions that can be made for a horse with ringbone. In generally, recommendations are along the lines of raising the heel of the horse’s hoof and cutting back the toe, under the rationale that it will make it easier for the horse to move forward over his toe (“breakover”). Unfortunately, while this makes some sense, at least in terms of how we think things should work, the lovely princess of theory frequently gets slain by the cruel dragon of reality. Otherwise stated, there’s no one way to shoe a horse with ringbone. Sometimes the something that you think should help really doesn’t. But it’s certainly worth working with your veterinarian and farrier to see if they might be able to provide some relief. You might have to try several different approaches, and none might work.

WHAT ABOUT SUPPORTING THE JOINT?

Why, I haven’t had time to ask you about that extraordinary case of ringbone you ran across in Texas. “Paradise Bend” by William Patterson White, 1920

I’m all for supporting your horse’s joints. I say, “Go, your horse’s joints.” But that’s about the extent of it. The fact of the matter is that all of the stuff that’s sold out there to provide joint support is about as important to the outcome of your horse’s joints as the cheerleaders for a football team are to the final score of the game. They’re nice to have and all, but they don’t make any real difference in how the game turns out. In my opinion, if all a product offers “joint support,” I wouldn’t pay much attention to it.

SURGERY?

There is one possible solution to ringbone: destroy the joint.

There is one possible solution to ringbone: destroy the joint.

Yep, in some horses, depending on which joint is involved, it is possible to fuse the bones on either side of the joint. Sometimes (rarely) it even happens on its own. Whether natural or surgical, two moving, painful bones get turned them into one bone. The success rate depends a lot of the size of the horse and whether it’s a front or back leg (back legs on small horses would he expected to do the best), but surgical fusion is an option, albeit an expensive one.

In humans, they don’t usually fuse an arthritic joint unless it’s a bone of the neck or spine. They just put in an artificial joint: a new hip, a new knee, a new shoulder. Unfortunately, that’s not an option for horses – they’re just too big, and put too much stress on implants. The point is that even in human medicine, with far more resources than are available in horse medicine, arthritic joints can’t be fixed. At some point, human surgeons just hoist the white flag and put in a new, artificial joint.

WHAT’S THE BOTTOM LINE?

I want you to take away a few points from this discussion. The first is that ringbone isn’t a death sentence. Often, particularly early in the course of disease, you can find a use level where your horse can do whatever he does reasonably comfortably, perhaps with the assistance of some medication. Just because he might not be able to do what he used to do doesn’t mean that he can’t do anything.

Still, when it comes to ringbone, as well as to any other any variation of osteoarthritis, here are some facts I want you to keep in mind.

Ringbone, and more broadly, osteoarthritis, is a common problem that occurs in horses all over the world.

Ringbone, and more broadly, osteoarthritis, is a common problem that occurs in horses all over the world.- There’s no known cure for the condition. Ringbone is progressive and it doesn’t let up.

- In some cases, surgery to fuse the affected joint can be performed, it does help some horses, but it’s expensive and it doesn’t always work.

- Ringbone can significantly impact the horse’s ability to get around, and take years off his life for riding or performance.

- There’s no intervention – no shoeing therapy, no medication, no device – that has been shown to prevent ringbone.

- There’s no intervention – no shoeing therapy, no medication, no device – that is available to stop the progression of the disease.

- Current therapies have little, if any, effect, and can rarely be associated with adverse events (e.g., effects from long-term use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications or reactions after substances are injected into joints).

- Treatments can cost horse owners a lot of money in terms of chasing after pointless therapies, supplements, etc.

I don’t want to sound like too much of a downer. A diagnosis of ringbone is never good news. But it also doesn’t mean that your horse is going to be unable to do anything. It also doesn’t mean that you have to chase after every unproven, expensive, useless therapy that’s out there in a frantic attempt to “help.” Even though it’s not good diagnosis, when it comes to ringbone you can usually find some level of use – perhaps with a bit of medication – that will allow you to enjoy your good friend for many years to come.

I don’t want to sound like too much of a downer. A diagnosis of ringbone is never good news. But it also doesn’t mean that your horse is going to be unable to do anything. It also doesn’t mean that you have to chase after every unproven, expensive, useless therapy that’s out there in a frantic attempt to “help.” Even though it’s not good diagnosis, when it comes to ringbone you can usually find some level of use – perhaps with a bit of medication – that will allow you to enjoy your good friend for many years to come.