A good number of the problems that beset horses have to do with their muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, etc. Rather than write all that out (and don’t forget joints and cartilage and associated tissues), we (anatomists, veterinarians, biologists, and the like) term the whole problematic – but extremely useful, in terms of getting around – package the musculoskeletal system. We could write a book about (and people have written many books about) problems with the horse’s musculoskeletal system.

A good number of the problems that beset horses have to do with their muscles, ligaments, tendons, bones, etc. Rather than write all that out (and don’t forget joints and cartilage and associated tissues), we (anatomists, veterinarians, biologists, and the like) term the whole problematic – but extremely useful, in terms of getting around – package the musculoskeletal system. We could write a book about (and people have written many books about) problems with the horse’s musculoskeletal system.

That said, in my opinion, life consists of people who generally fall into one of two categories: splitters and lumpers. Splitters like to break everything down to its smallest part, seemingly unable to rest easy unless every stone has been turned over. Splitters also tend to want to do “everything possible” when it comes to diagnosis and treatment of their horse and, veterinary medicine being what it is today, a splitter-like attitude is often encouraged.

I tend to be a lumper. Lumpers tend to make piles out of everything. As such, in most cases, I’m more than happy to have a general idea about what’s going on with a horse, and go on from there. Sometimes the complicated (and usually expensive) stuff that splitters insist on is valuable, but in a lot of cases, it’s just information gathering for the sake of gathering information; all of that information may not really change treatment much. But I digress.

I tend to be a lumper. Lumpers tend to make piles out of everything. As such, in most cases, I’m more than happy to have a general idea about what’s going on with a horse, and go on from there. Sometimes the complicated (and usually expensive) stuff that splitters insist on is valuable, but in a lot of cases, it’s just information gathering for the sake of gathering information; all of that information may not really change treatment much. But I digress.

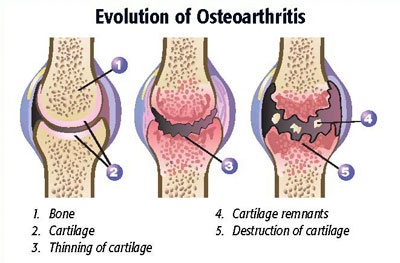

Understanding my proclivity for lumping, I want to grossly divide the musculoskeletal system into two types of tissues: hard and soft. Hard tissues are bone, and bone is – obviously – a very important tissue, as the entire horse is supported by the stuff. We’re not going to talk about hard tissues (at least not today).

The classic appearance of a badly “bowed” tendon (left leg, in case you didn’t know)

Instead, we’re going to talk a bit about soft tissues. Of course, people have recognized soft tissue injuries in horses for a long, long time. Soft tissue injuries come with all sorts of names. Sometimes those names are quite colorful, for example, a “bowed tendon,” so-named because when a tendon gets injured, it swells, and the swelling can distort the shape of the tendon so that it looks like an archer’s bow. Other names, like “desmitis of the collateral ligament of the distal interphalangeal joint” are much more imposing. Vernacular aside, both of these injuries – and many, many more – are soft tissue injuries, that is, they don’t primarily affect the bone. When it comes to soft tissues in the horse’s musculoskeletal system, there are far more similarities than there are differences.

One of the similarities is that, depending on their severity, soft tissue injuries can sometimes take an exceedingly long time to heal. There are a lot of reasons for this; among them is the fact that ligaments and tendons and such are not very active, metabolically speaking. Tissues that are metabolically active tend to heal quickly: no matter how much you want them to heal more quickly. So, for example, if your horse cuts himself, skin cells, which are pretty active, metabolically speaking, get to work and, barring unforeseen circumstances, heal the cut pretty quickly. The other end of the spectrum of metabolic activity can be seen in the nervous system. That’s one of the reasons why, for example, when there’s an injury to the nervous system, it heals pretty slowly, if at all.

Soft tissue structures – specifically tendons and ligaments – are among the tissue that are not very active, metabolically speaking. There are a lot of reasons for this lack of activity, including a relatively poor blood supple (compared to other tissues), and the fact that tendons and ligaments are very dense structures, comprised mainly of a protein called collagen. These reasons mean that, fundamentally, soft tissue injuries are going to heal at their own pace and, in fact, there’s really not much you can do to get them to heal any faster. The relatively poor blood supply means that there is relatively poor delivery of oxygen and nutrients that are necessary for tissue repair. The tightly packed collagen fibers that make up the soft tissues also heal very slowly, compared to the healing of other tissues, such as muscle or skin. Add to that the fact that tendons and ligaments are constantly being loaded when the horse moves – and it’s a heavy load – and you have a lot of stress on a healing soft tissue structure. In fact, if you’re in too much of a hurry for soft tissue to heal, that stress can potentially reaggravate a soft tissue injury if it’s not carefully managed.

Soft tissue structures – specifically tendons and ligaments – are among the tissue that are not very active, metabolically speaking. There are a lot of reasons for this lack of activity, including a relatively poor blood supple (compared to other tissues), and the fact that tendons and ligaments are very dense structures, comprised mainly of a protein called collagen. These reasons mean that, fundamentally, soft tissue injuries are going to heal at their own pace and, in fact, there’s really not much you can do to get them to heal any faster. The relatively poor blood supply means that there is relatively poor delivery of oxygen and nutrients that are necessary for tissue repair. The tightly packed collagen fibers that make up the soft tissues also heal very slowly, compared to the healing of other tissues, such as muscle or skin. Add to that the fact that tendons and ligaments are constantly being loaded when the horse moves – and it’s a heavy load – and you have a lot of stress on a healing soft tissue structure. In fact, if you’re in too much of a hurry for soft tissue to heal, that stress can potentially reaggravate a soft tissue injury if it’s not carefully managed.

Unfortunately, soft tissue injuries are all-to-common in horses, especially those used for athletic activities, and their response to treatments is often unsatisfactory, both in terms of the time it takes for repair, as well as the quality of the repair. Otherwise stated, soft tissue injuries tend to take a long time to heal and, when they do heal, they may not return to their preinjury state of normal. In addition, the more severe the injury, the less likely it is that the tissue will return to pre-injury normal. That’s not to say that the healed tissue won’t be strong enough for the horse to return to work (a lot of whether or not the horse will be able to return to his job depends on the work that the horse is supposed to return to), but it won’t return to it’s preinjury state of normalcy.

Unfortunately, soft tissue injuries are all-to-common in horses, especially those used for athletic activities, and their response to treatments is often unsatisfactory, both in terms of the time it takes for repair, as well as the quality of the repair. Otherwise stated, soft tissue injuries tend to take a long time to heal and, when they do heal, they may not return to their preinjury state of normal. In addition, the more severe the injury, the less likely it is that the tissue will return to pre-injury normal. That’s not to say that the healed tissue won’t be strong enough for the horse to return to work (a lot of whether or not the horse will be able to return to his job depends on the work that the horse is supposed to return to), but it won’t return to it’s preinjury state of normalcy.

Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram, in a brief moment of levity

But back to the unsatisfactory healing part. Let’s go back in time to 1869, when Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram, a British Army cavalry officer, expert on horses and a Conservative politician who must have had a convenient nickname, authored the book, “Horses and Stables.” You can get a sense of how far we’ve come in the treatment of tendon injuries if you look into his book (which we are going to do).

As far as treatment goes, Sir Frederick said, “In all cases of doubt, as to whether the heat and swelling in any particular case arise from injury of the tendon or ligament, or merely from injury to its sheath or perhaps only from an ordinary blow or such like cause, the safer plan is to rest the horse and foment the part [NOTE: this is an old medical term, meaning to bathe a part of the body with warm or medicated lotions], until by rapid and complete disappearance of all symptom of mischief we can be quite sure, that there is nor has been injury to any of those important but slowly repaired structures.”

First off, the writing style in the mid-19th century was absolutely charming, don’t you think? But second, you can see that even back then, experts recognized that you need to give soft tissue injuries of the horse the time to heal, regardless of what you foment them with. And we certainly do foment away today (I just learned this term, writing this article, and I’m not going to forget it), be it with DMSO or paints or liniments or water from a hose or any number of other nostrums. Still, the bottom line is that today, soft tissue injuries need time to heal, just as they did in the 19th century.

Moving on, Sir Frederick noted, “From similarity of the cause producing the injury, and likewise from similarity of organization and structure in all tendons and ligaments, the treatment, which we are called upon to adopt, is in most cases nearly similar.”

Moving on, Sir Frederick noted, “From similarity of the cause producing the injury, and likewise from similarity of organization and structure in all tendons and ligaments, the treatment, which we are called upon to adopt, is in most cases nearly similar.”

What that means, of course, is that Sir Frederick recognized that the tendon and ligament injuries tend to happen for the same reasons, they’re very similar anatomically, and the treatment of tendon and ligament injuries is pretty much the same, no matter which tendon or ligament is injured. That’s still the case today.

Tellingly, Sir Frederick went on to say, “The skill of the veterinary surgeon lies more in detecting the exact seat of injury that in the mode of treatment.” That, too, is the same as today. That is, today, we (veterinary surgeons) can use a lot of new tools (ultrasound, MRI, and such), to determine exactly what and where the horse’s soft tissue injury is. That’s great, and very important. The problem is that we still can’t do much more about them than we could in Sir Frederick’s time, in spite of us having a whole lot more choices of things to do.

Honestly, I think it’s kind of demoralizing to learn that, after, oh, 170 years or so, you can’t really do all that much to help equine soft  tissue injuries heal either better of faster than you could back then. But on the topic of doing something, Sir Frederick noted, “Many practitioners however get over this difficulty, and veil their ignorance by blistering, firing, or putting in setons all over the affected leg or legs.” [NOTE: a seton was a thread or bit of material inserted beneath the skin to provide drainage]

tissue injuries heal either better of faster than you could back then. But on the topic of doing something, Sir Frederick noted, “Many practitioners however get over this difficulty, and veil their ignorance by blistering, firing, or putting in setons all over the affected leg or legs.” [NOTE: a seton was a thread or bit of material inserted beneath the skin to provide drainage]

Since Sir Frederick’s day, we’ve got a lot more to offer for soft tissue injuries, of course than, “Firing, blistering, or putting in setons.” In no particular order, we’ve got magnets and lasers, stem cells and PRP, electromagnets and therapeutic ultrasound, support boots, a whole pharmacy full of anti-inflammatory medications, DMSO and shockwave therapy, shelves of supplements, anti-oxidants and herbs, and I’m probably missing a few.

Once again, Sir Frederick was prescient. He noted, “We do not say that such treatment is altogether ineffectual. We know that many horses recover and become sound under it – though principally, we think, on account of the amount of time and rest which such treatment necessitates.”

Once again, Sir Frederick was prescient. He noted, “We do not say that such treatment is altogether ineffectual. We know that many horses recover and become sound under it – though principally, we think, on account of the amount of time and rest which such treatment necessitates.”

Sir Frederick is leading us right up to the present day. The fact of the matter is that, so far, no treatment that we’ve come up with since Sir Frederick’s Day has been shown to result in better healing quality than sufficient rest. I’ll add to that prescription supervised rehabilitation, that is, you want to gradually return the horse to work after the injury has had enough time for healing. In fact, if that’s all you do for your horse’s soft tissue injury, you’ve probably done all you need to do. Oh, and make sure you’re ready to be patient.

Your horse can certainly return to work from most soft tissue injuries, although, to be fair, the more severe the injury, and the more strenuous the work expected of the horse on his return, the less likely it is that he’ll be able to go back to what he was doing. Nonetheless, in spite of lots and lots of treatment options – many of which are quite expensive – the fact is that nothing has been shown to lead to a better outcome for equine soft tissue injuries than appropriate rest and rehabilitation. You can take that to the bank.