Lameness, as pretty much everyone knows, is the bane of anyone who wants to ride a horse: particularly horses that are being asked to perform. Although the most common site of lameness by far is the horse’s hoof, lameness can originate from just about anywhere in the horse’s body. One of the more uncommon areas from which lameness arises is the horse’s stifle joint.

Lameness, as pretty much everyone knows, is the bane of anyone who wants to ride a horse: particularly horses that are being asked to perform. Although the most common site of lameness by far is the horse’s hoof, lameness can originate from just about anywhere in the horse’s body. One of the more uncommon areas from which lameness arises is the horse’s stifle joint.

WHAT’S A STIFLE?

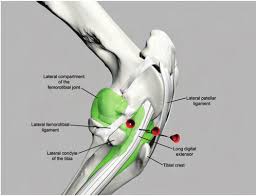

The stifle joint is, of course, in the horse’s hind leg. It’s analogous to the human knee joint. However, the horse’s stifle is quite a bit different from the human knee. For example, the stifle “joint” is actually made up of three separate joints.

ASIDE: Just so as to keep things confusing, the joint that most people call the horse’s knee is analogous to the human wrist. I have no idea why this is. Even the Unabridged Oxford English Dictionary says that the word, “stifle,” is “of obscure origin.”

ASIDE: Just so as to keep things confusing, the joint that most people call the horse’s knee is analogous to the human wrist. I have no idea why this is. Even the Unabridged Oxford English Dictionary says that the word, “stifle,” is “of obscure origin.”

Horse’s have been observed to have problems with the stifle joint for a long, long time. Most commonly, this was seen as upward fixation of the patella (knee cap), where the horse’s leg would get stuck, that is, it couldn’t bend because the patella slipped out of its groove and was clamped in place by one of the three ligaments of the horse’s kneecap (this is another difference for horses – they have three patellar ligaments whereas humans just get one big patellar tendon). When the patella gets stuck in a horse, the horse, in another bit of the unique verbiage that has been around for hundreds of years, may be said to be “stifled.”

As we’ve learned more and more about horse joints, we’ve been able to get better images, so we have a much better idea what’s going on inside them. Sometimes, that means that we can even provide effective treatments. The stifle seems to have also become the subject of a lot more attention than in years past. Whereas previously, stifles never got much attention unless there was an obvious problem, now, at least in certain circles, there a lot of horses that get needles stuck into their stifle joints with somewhat alarming regularity.

But I digress. That’s a different article.

But I digress. That’s a different article.

STIFLE SURGERY

Under any circumstances, trying to figure out how to diagnose and treat many of the problems related to the equine stifle joints can be a frustrating challenge. It’s a big joint and it’s an important joint. Sometimes when something wrong can be found in one or more of the three joints that make up the equine stifle, surgery may be recommended, for example, for treatment of conditions such as osteochondrosis (OCD) or tears of the meniscus.

When you’re trying to figure out whether you should do surgery on your horse’s stifle – assuming that you horse has a problem there, of course – it can be somewhat disheartening to learn that there really isn’t a lot of data out there on how horses do after stifle surgery. Oh, there are many detailed descriptions of treatment options, a whole bunch of surgical approaches, several different imaging techniques, however, there are relatively few studies that look at how horses affected with various conditions of the stifle actually do after surgery.

When you’re trying to figure out whether you should do surgery on your horse’s stifle – assuming that you horse has a problem there, of course – it can be somewhat disheartening to learn that there really isn’t a lot of data out there on how horses do after stifle surgery. Oh, there are many detailed descriptions of treatment options, a whole bunch of surgical approaches, several different imaging techniques, however, there are relatively few studies that look at how horses affected with various conditions of the stifle actually do after surgery.

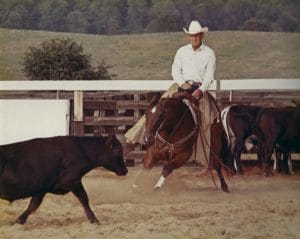

Which makes a recent study from the journal Veterinary Surgery so interesting. To answer the question, “How do they do after stifle surgery?” investigators at Colorado State University looked at 82 Western Performance horses – CLICK HERE to see an abstract of the study – and followed them up to see how they did. The study also tried to see if they could predict factors that would make it more likely than not that a horse would return to full performance after surgery.

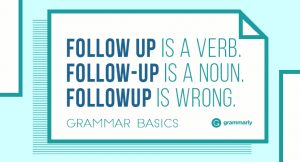

Long Term Follow-Up

Follow-up is one of the things that distinguished this study from most all of the others. The researchers looked at the medical records, but they also did telephone interviews with the owners at least two years after surgery was performed. While you don’t often see this kind of follow-up in veterinary medical studies, but it is critically important in helping to advise owners about the choices that they’re going to make for their horse: and the money they are going to spend, as well. And, in regard to money, the researchers analyzed the treatments given after surgery, to see if there was any association between the treatments given and a return to athletic performance.

Follow-up is one of the things that distinguished this study from most all of the others. The researchers looked at the medical records, but they also did telephone interviews with the owners at least two years after surgery was performed. While you don’t often see this kind of follow-up in veterinary medical studies, but it is critically important in helping to advise owners about the choices that they’re going to make for their horse: and the money they are going to spend, as well. And, in regard to money, the researchers analyzed the treatments given after surgery, to see if there was any association between the treatments given and a return to athletic performance.

Results

The horses involved in the study were all Western Performance horses, including 38 cutting horses, 13 Western pleasure horses, and 13 reining horses (I know that doesn’t add up to 82, it’s just that there were a whole bunch of different disciplines). Kind of sadly, only 32 of the 82 horses – approximately 39% – returned to their intended use after surgery. For what it’s worth, that’s pretty much the same thing that another study of 44 horses, done in 2009, found (CLICK HERE for a link to the abstract). In that study, only 13 of 44 horses (37%) returned to their previous level of performance after stifle surgery.

The horses involved in the study were all Western Performance horses, including 38 cutting horses, 13 Western pleasure horses, and 13 reining horses (I know that doesn’t add up to 82, it’s just that there were a whole bunch of different disciplines). Kind of sadly, only 32 of the 82 horses – approximately 39% – returned to their intended use after surgery. For what it’s worth, that’s pretty much the same thing that another study of 44 horses, done in 2009, found (CLICK HERE for a link to the abstract). In that study, only 13 of 44 horses (37%) returned to their previous level of performance after stifle surgery.

Prognostic Factors

Still, even though the overall results weren’t that great, the investigators did find a number of factors that were associated with poorer outcomes. I think these are really important, if it comes to you trying to make a decision for your horse. Here they are:

As might be suspected, older horses have a decreased chance of returning to their previous level of performance.

As might be suspected, older horses have a decreased chance of returning to their previous level of performance.- The degree of lameness was directly associated with outcome; the worse the lameness, the worse the chance that the horse would make a successful return to performance after surgery.

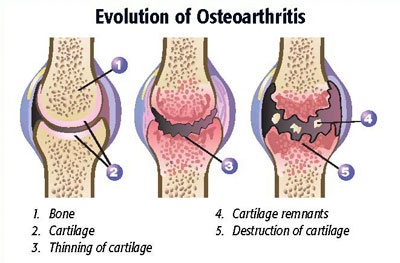

- Horses with more severe problems have less of a chance of returning to work than do horses with less severe problems (you might be able to see this on an X-rays, for example). This is usually the case in medicine, by the way.

- The duration of lameness was also an important prognostic factor; the longer the horse had been lame, the less the chance that he would return to his previous level of performance.

- Finally, if there were partial thickness lesions of the cartilage noted at the time of surgery, the chance that the horse would successfully return to work decreased.

Post-Operative Therapies

Here’s another part of the study that I think is important. I think it has some broader implications for treatment of all joints in all horses, as well.

After surgery, it’s pretty common for horse owners to be asked to invest in a bunch of different products to “help” with their recovery. There are all sorts of very appealing rationales for these sorts of therapies – e.g., to decrease inflammation, “protect” cartilage, provide “building blocks” for cartilage, etc. The motivation for employing them is also good; I mean, don’t you want to do “everything that you can” to help your horse? And while, the choice of such therapies seems to depend mostly on the opinions of the prescribing veterinarian(s), there is little scientific evidence to suggest that any of them make a significant difference in outcomes. They certainly didn’t in this study.

After surgery, it’s pretty common for horse owners to be asked to invest in a bunch of different products to “help” with their recovery. There are all sorts of very appealing rationales for these sorts of therapies – e.g., to decrease inflammation, “protect” cartilage, provide “building blocks” for cartilage, etc. The motivation for employing them is also good; I mean, don’t you want to do “everything that you can” to help your horse? And while, the choice of such therapies seems to depend mostly on the opinions of the prescribing veterinarian(s), there is little scientific evidence to suggest that any of them make a significant difference in outcomes. They certainly didn’t in this study.

Here is a list of the post-operative therapies used:

intra‐articular stem cells

intra‐articular stem cells- intra-articular corticosteroids

- intra-articular interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP)

- intra-articular hyaluronan/polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (Adequan®)

- Systemic nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

- Systemic hyaluronic acid (Legend®)/polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (Adequan®)

- Oral joint supplements

Sound familiar? All of these treatments were given with good rationales: given with the best of intentions. All of them have some rather optimistic claims. However, exactly none of these commonly prescribed therapies made any difference in whether the studied horses returned to their previous level of performance.

CONCLUSIONS

www.savagechickens.com

While the findings from this study aren’t particularly optimistic, I think that they are really important. From this, and other studies, one can reasonably conclude that the prognosis for full return to athletic function after stifle surgery is really quite guarded. Less than 40% of studied horses in two studies returned to their intended use following stifle surgery. Depending on risk factors, the chances that your horse will do well may be even less. In fact, make sure you understand what’s wrong with your horse and what the chances of a good outcome are before you decide to do ANY treatment for your horse.

Finally, for all of the therapeutic options that are available for post-operative care, given both directly into the joint, as well as systemically, none of them may be helpful in returning the horse to its previous level of use. In spite of what you may have read or been told, they aren’t going to prevent arthritis, either. I’d certainly never criticize anyone who would try to do everything that can be done for a horse, but while the rationale for the use of such therapies may be completely good, the reality is that current information would indicate that they are likely to be mostly a waste of time and money, at least after stifle surgery, and probably for a lot of other things. There is no reason to add financial insult to equine injury.

The death knell for an optimistic prognosis is often long-term follow-up. Hopefully, we learn.