Some things, like breathing, are completely involuntary – we don’t even think about them. Others, like deciding which movie that we’re going to see, take a bit more effort. Personally, I think that the impulse to put “something” on a horse’s wound is an involuntary response.

People have been putting things on wounds since, well, since there were wounds. The history books are full of wound treatments such as otter feces (a 6th century Chinese favorite), or various herbal plasters, or urine (yes, urine – it’s been used for millenia, it’s readily available, and it’s not obviously harmful to a wound). And, often, after stuff got put on them, wounds healed. We know a lot more about wounds now than we did then – the treatments have sure changed – but the impulse to put something on them hasn’t changed a bit. And, if they heal with some of the stuff that people have put on them, you can pretty safely conclude that wounds have a pretty powerful urge to heal.

Wounds are generally divided into two types. They are:

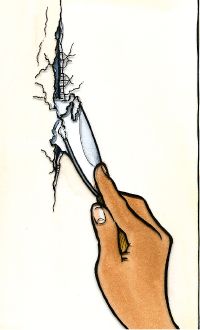

Type 1. Wounds that can be sewn up. This would include wounds created at surgery, as well as wounds that occur from such equine-assisted endeavors as running into feeders, fences, or the occasional screw head that protrudes 1/16 of an inch from the corner of the stall, a screw head that would seem to require a concerted effort on the part of the horse to find, much less on which to become lacerated. (If you want to read more about Type 1 wounds, CLICK HERE.)

2. Wounds that can’t be sewn up. That is, all of the wounds that, for one reason or another aren’t included in #1. (If you want to read more about Type 2 wounds, CLICK HERE.)

Based on current knowledge about wound healing, here’s what you need to know putting stuff on category #1. It’s short, sweet, and probably contrary to your immediate impulses. If a category #1 wound has been properly cared for and sutured shut, putting some liquid, ointment, or cream on the wound is unlikely to help, and may hurt. That’s right; putting some this or that sort of muck on a properly sutured wound pretty much does nothing to help healing.

And it’s not just that it doesn’t help – it might hurt. Take commonly used antibiotic ointments, such as “Triple Antibiotic” ointment, or Neosporin®. A number of studies in human medicine have shown that, when compared to products that contain antibiotics, wounds treated with a simple petrolatum-based ointment heal more quickly. Plus, using antibiotics willy-nilly helps cause bacterial resistance to antibiotics – we certainly don’t want to be creating species of superbacteria that can’t be killed.

And it’s not just that it doesn’t help – it might hurt. Take commonly used antibiotic ointments, such as “Triple Antibiotic” ointment, or Neosporin®. A number of studies in human medicine have shown that, when compared to products that contain antibiotics, wounds treated with a simple petrolatum-based ointment heal more quickly. Plus, using antibiotics willy-nilly helps cause bacterial resistance to antibiotics – we certainly don’t want to be creating species of superbacteria that can’t be killed.

BOTTOM LINE? If your horse has a wound that’s been sutured, you generally don’t need to spray it, soak it, or glop it up with antibiotic-containing ointments, or much of anything else. It’ll be fine, assuming that there’s not some other problem (like a splinter in the wound, or something). And, if there is some other sort of problem in the wound itself, such as in infection or a piece of the stall or corral, putting an antibiotic on top of the wound won’t help anyway.

Now, for the other wounds, category #2, the wounds that can’t be sewn up: the ones that you’ll worry yourself to death about.* If your horse cuts itself, and it can’t be sewn up, it’s going to have to heal up on its own. And, best of all, it’s going to try to heal on its own. And, as has likely been the case for eternity, you’re going to want to put something on it (whether it needs it, or not).

There are quite literally dozens of products that you can apply to category #2 wounds, all neatly arranged at your local tack store. This mere fact should sound alarm bells. When there are dozens of possible treatments for something, all of which can be obtained without a prescription, or even a glance from your veterinarian, this means that one of two things is likely to be true.

1. None of them works very well.

2. Even if they work (to some extent), none of the really makes much difference.

If you’re confused as to what the vast array of wound care products all do, here’s one useful way to break them down: by color. Wound dressings are typically either red, brown, silver, violet, blue, white, or yellow. Nitrofurazone, an antibiotic, which starts yellow, turns orange if it is exposed to sunlight. I cannot remember having seen wound dressings in the green spectrum. Black also seems underrepresented, perhaps because black would seem morbid, and pessimistic.

If you’re conservative, you’ll probably find that silver (aluminum sprays) are hidden fairly well by the color of a dappled grey – dark blue or violet sprays or liquids nearly disappear in the darker areas of a bay, or on a black. On the other hand, if you like drawing attention to things, silver and yellow (nitrofurazone) sprays stand out dramatically from the coat of a dark horse, while a dark blue or violet spray will make your grey horse or a palomino look like he’s just been marked down at the garage sale. Use any of them according to your preference or color aesthetic – things will probably end up just fine no matter which color you choose.

Most all of these products will work on category #2 wounds because they won’t get in the way of what the body wants to do anyway: heal. However, there are some things out there that you should just stay away from.

Products that have caustic chemicals in them just burn the wound surface, although freely available, are not a great thing to put on wounds. In fact, one popular product that you can buy is mostly soda lime – that’s right, the stuff you throw on the bottom of your horse’s stall to soak up urine. One of my professors said that you should never put anything on a horse’s wound that you wouldn’t put in your own eye. Frankly, I think that’s a great rule to follow. If you don’t know if a product is caustic, ask your veterinarian (or send me an email).

Products that have caustic chemicals in them just burn the wound surface, although freely available, are not a great thing to put on wounds. In fact, one popular product that you can buy is mostly soda lime – that’s right, the stuff you throw on the bottom of your horse’s stall to soak up urine. One of my professors said that you should never put anything on a horse’s wound that you wouldn’t put in your own eye. Frankly, I think that’s a great rule to follow. If you don’t know if a product is caustic, ask your veterinarian (or send me an email).

Lots of wound care products say that they’re “natural.” If you didn’t know, I pretty much hate the word “natural” when it comes to medicine; that includes wound care, too. I suppose one could argue that wounds themselves are “natural,” and the fact of the matter is that if you leave many wounds alone so that they can heal “naturally,” things will be fine. Of course, sometimes, you can end up with a big mess on your hands – if you don’t like how things are going, call your veterinarian.

Lots of wound care products say that they’re “natural.” If you didn’t know, I pretty much hate the word “natural” when it comes to medicine; that includes wound care, too. I suppose one could argue that wounds themselves are “natural,” and the fact of the matter is that if you leave many wounds alone so that they can heal “naturally,” things will be fine. Of course, sometimes, you can end up with a big mess on your hands – if you don’t like how things are going, call your veterinarian.

“Natural” wound products usually include stuff like aloes, anti-oxidants, oils (tea tree is one that has some effect, and can also really irritate the skin of some horses), and antibacterials and all sorts of other anti-anything-bad compounds that Mother Nature has apparently so graciously provided. You can also dress category #2 wounds with substances like honey (which, honestly, has some underlying medical support, but its usefulness has absolutely nothing to do with its naturalness), or sugar (usually mixed with a dilute povidone-iodine** solution, which makes the sugar not only brown, but also easier to apply). I even had a client accidentally dress her horse’s wound with a combination of povidone-iodine and salt (instead of sugar), which went on for about two days, until the horse made it clear that he was not going to tolerate having salt rubbed into his wound any more. The wound did great, however.

Often, wonder-wound-products are even accompanied by photos, such as this gruesome montage, which shows a wound that, over time, miraculously healed, leaving a not-entirely-too-bad, terrific conversation starter of a scar. And, of course, you’re left with the understanding that this sensational wound probably would not have healed had it not been for the wonderful powers of the product. Of course, if you read the label, you’ll find out that they contain not much of anything – one currently popular “miracle” treatment is 99.something percent water, with a very small amount of bleach, for only about $30 per 8 oz.

Often, wonder-wound-products are even accompanied by photos, such as this gruesome montage, which shows a wound that, over time, miraculously healed, leaving a not-entirely-too-bad, terrific conversation starter of a scar. And, of course, you’re left with the understanding that this sensational wound probably would not have healed had it not been for the wonderful powers of the product. Of course, if you read the label, you’ll find out that they contain not much of anything – one currently popular “miracle” treatment is 99.something percent water, with a very small amount of bleach, for only about $30 per 8 oz.

And the fact is, the gruesome wound would have healed anyway and just as quickly – like I said, wounds love to heal.

In fact, when it comes to wounds, there are two very simple rules to keep in mind.

RULE ONE = All wounds want to heal. If the wound is healing with what you’re doing, don’t change anything, even if what you’re doing doesn’t make much difference, because you’ll probably just mess things up if you start changing them. As long as it’s going well, leave well enough alone.

RULE TWO = If a wound isn’t healing right, something is wrong. That’s when you need to call your veterinarian.

Mostly, it doesn’t matter too much what you put on your horse’s wound. But, if you’re wondering or worried, call your veterinarian. There are some very basic principles of wound healing, and your veterinarian knows them very well. He or she would love to hear from you.

***********************************************************************

* There are all sorts of reasons that horse wounds can’t be sewn up. For example, you might have found the wound a day after it happened, in which case the wound is likely to be infected. If you try to sew infection into the horse’s body, the horse’s body will object, and the sewn wound will open up. Or, maybe there’s been tissue lost, and the edges of the wound can’t be brought back together – this is a particular problem on the lower limbs, where the skin is pretty much shrink-wrapped onto the bones. After such a wound, there’s may not be enough skin left to pull back together.

** The most well-known brand of povidone-iodine solution is Betadine.®