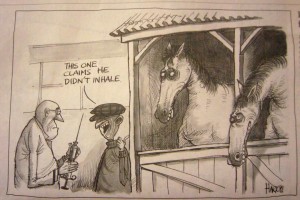

The subject of drugs and horses shows up fairly regularly, and is a concern for many people, in a variety of horse related disciplines. For example, in 2012, the New York Times sponsored a series of articles about drugs and horse racing (mostly Thoroughbred racing, but also a bit on Quarterhorse racing, showing how one can launder money through the horse world), and it’s a problem in show horses, too.

The subject of drugs and horses shows up fairly regularly, and is a concern for many people, in a variety of horse related disciplines. For example, in 2012, the New York Times sponsored a series of articles about drugs and horse racing (mostly Thoroughbred racing, but also a bit on Quarterhorse racing, showing how one can launder money through the horse world), and it’s a problem in show horses, too.

It’s not a simple matter of, “There are bad people who give horses drugs.” It’s also not necessarily a matter of, “All drugs are bad.” You see, this drugs and horses thing is a multi-headed beast, In my opinion, it’s going to be pretty hard to resolve questions pertaining to the use of drugs in performance horses to everyone’s satisfaction. That’s not to say it’s not worth trying, just that it’s going to be hard, and it’s going to require a concerted effort. Whether everyone has the will to do it, well, that’s another problem.

An article that started a recent furor about horse racing, “Big Purses, Sore Horses, and Death,” can be read if you CLICK HERE. The article about drugs in the show horse industry can be seen if you CLICK HERE. Both articles talk about the same sort of thing – lots of drugs, little oversight, pressure to perform. There appear to be fewer drug-related deaths in show horses than in Thoroughbred racing, of course, but really, that sort of news should be listed under the heading of “damning with faint praise.”

The articles describe a culture where horses are asked to perform with little regard to their health, and are given drugs to try to improve their performance. Both legitimate and illegal medications, coupled with lax and uncoordinated oversight, are accused of having put the the safety and welfare of horses at risk. The drugs, it is alleged, are said to be responsible for horses dying – something along the lines of 24 horses a week on the Thoroughbred racetracks, and at least one pony at a horse show.

The articles describe a culture where horses are asked to perform with little regard to their health, and are given drugs to try to improve their performance. Both legitimate and illegal medications, coupled with lax and uncoordinated oversight, are accused of having put the the safety and welfare of horses at risk. The drugs, it is alleged, are said to be responsible for horses dying – something along the lines of 24 horses a week on the Thoroughbred racetracks, and at least one pony at a horse show.

These articles are not exactly the sorts of things that the horse world is enthusiastic to have brought up. It kind of gives everyone a black eye. Still, given the much publicized concerns about the use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in human athletic endeavors, and society’s concerns about them, I think it’s a really good idea to get discussions out in the open.

It’s not like investigating drugs in horses is new. Using search terms “doping horse racing,” in the NYT search engine, I found that the NYT has been pursuing the subject of doping in horse racing for a long time.

YOU: “Oh, come on. “How long can it be?”

ME: “Since 1901.”

Yep, all the way back in 1901 the Times published an article talking about “doping” racing horses with a mystery stimulant (although alcohol and caffeine were generally apparently considered OK). Articles appeared year after year – in 1966, Dr. Robert Aries, a noted chemist, accused horse racing authorities of a “conspiracy of silence” about horse drugging techniques. The reports of drugs in racing continued all the way up to the Preakness of 2012, where it was reported that of 20 trainers, only 2 had never been cited for doping. The inclusion of show horses just ups the ante on the drugs and horses issue – and trust me, there are other equestrian industries out there that have yet to be scrutinized.

Anyway, just by reading the New York Times, a person can quite reasonably conclude that trying to improve horses’ performances by giving them performance enhancing substances has been going on for over 100 years – at least as documented in newspaper articles about racing. And, it’s also reasonable to conclude that, up to now, in the United States, no one has figured out an effective way to do control it across the board. There are probably several reasons.

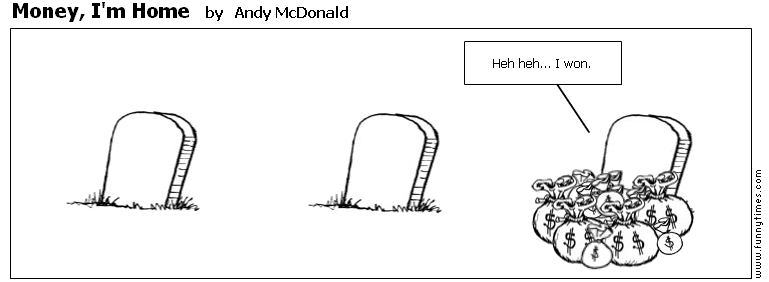

1. Money – Money, money, money. Top level horse competition is big business. Win a big race = win a lot of money, and there are stud fees, to be collected, too! Show jumpers regularly competes for prizes of hundreds of thousands of dollars around the world. Cutting horses, reining horses, and barrel horses all compete at the top levels for big prizes. Sometimes it seems like everyone is in on the money game.

But it’s NOT everyone. As with any business there are the honest and caring horse people who do the best they can for the horses they have, who retire them if they can’t do the job, or downgrade their job if they are starting to have trouble. But there are also the ones to whom winning/money is everything and the horse means very little. Good horsemen and woman can win without performance enhancing drugs, but drugs offer the alluring possibility of a short cut. And, honestly, who doesn’t like things to be easy?!

In addition, many people look for an edge, or are concerned with the pharmacological equivalent of, “Keeping up with the Joneses.” Some folks are looking to supply that edge, including some veterinarians, too. The NY Times also has an article about that – CLICK HERE to read it. Nobody’s hands are really clean here. Some of the illegal drug use in performance horses has been pushed by “horse show vets” and “sports medicine vets;” on the other hand, horse owners and trainers may put pressure on veterinarians, with the implied threat of losing business if wishes aren’t complied with. There are interesting drug combinations, “naturally occurring substances” that affect behavior, and medications for which there are no current tests. In my opinion, the use of just about any substance in an attempt to enhance performance in an otherwise healthy horses is just terrible, and it is a blemish on everyone. It also makes it harder for people that don’t want to provide drugs to horses to in order to compete.

In addition, many people look for an edge, or are concerned with the pharmacological equivalent of, “Keeping up with the Joneses.” Some folks are looking to supply that edge, including some veterinarians, too. The NY Times also has an article about that – CLICK HERE to read it. Nobody’s hands are really clean here. Some of the illegal drug use in performance horses has been pushed by “horse show vets” and “sports medicine vets;” on the other hand, horse owners and trainers may put pressure on veterinarians, with the implied threat of losing business if wishes aren’t complied with. There are interesting drug combinations, “naturally occurring substances” that affect behavior, and medications for which there are no current tests. In my opinion, the use of just about any substance in an attempt to enhance performance in an otherwise healthy horses is just terrible, and it is a blemish on everyone. It also makes it harder for people that don’t want to provide drugs to horses to in order to compete.

2. Prestige – If it’s not money, it’s prestige. It’s cool to be at the top of your sport. It carries a certain cachet. Top riders, owners of top horses, top trainers, and the veterinarians that attend to those horses (and those people) achieve some level of personal satisfaction at having “made it.” Some will stoop to just about any level to do so. Prestige is worth a lot. If a top rider says something is good, then pretty much everyone will try it. Just look at the paid endorsements on just about any page of your horse magazines – it’s back to #1.

3. Competitiveness – There’s a well-known survey in sports, known as the Goldman Dilemma. Researcher Bob Goldman asked elite athletes in the 1980s whether they would take a drug that guaranteed them a gold medal but would also kill them within five years. More than half of the athletes said yes. He did the same survey every two years for the next decade, and the results were always the same. About half of the athletes were quite ready die in five years if they could just win a gold medal.

It took a while before researchers got around to asking non-athletes the same question. But in a survey published online in February, 2009 in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, exactly 2 of the 250 people surveyed in Sydney, Australia, said that they would take a drug that would ensure both success and an early death. The head researcher concluded that “elite athletes are different from the general population, especially on desire to win.”

That’s probably why, for some folks, drugs in performance horse disciplines is really no big deal. Those people are so competitive that they will do just about anything to win. While it is inconceivable for someone who may be just as competitive as anybody, but who operates by a strict code of rules to think about drugging a horse to win a weekend blue ribbon, it may become quite another matter to someone who is competing for a million dollar prize against the best riders and the best horses in the world. But in a hypercompetitive environment, with little concern for rules, if a top trainer said that he was feeding his winning horse a pint of kerosene every morning, you can pretty much bet that there would be a run on the camping stores the next day.

4. Laziness – Drugs can be a shortcut for proper training, and competent riding ability, too. Some riders seem to expect instant success with no work or effort from them – it’s a lot easier to drug a horse than it is to train it. In addition, some riders seem to want to do well without working hard – you can’t learn to be a good horseperson if all you do is show up at the barn and find that your boots have been shined. Some trainers may take these same people to shows and put them on nice horses that the clients might not be able to rider otherwise, thanks to drugs. And they can make a good living doing it (back to #1). Everybody’s happy (no one asks the horse)!

4. Laziness – Drugs can be a shortcut for proper training, and competent riding ability, too. Some riders seem to expect instant success with no work or effort from them – it’s a lot easier to drug a horse than it is to train it. In addition, some riders seem to want to do well without working hard – you can’t learn to be a good horseperson if all you do is show up at the barn and find that your boots have been shined. Some trainers may take these same people to shows and put them on nice horses that the clients might not be able to rider otherwise, thanks to drugs. And they can make a good living doing it (back to #1). Everybody’s happy (no one asks the horse)!

5. Problems with oversight – If drugs are going to be taken out of the performance horse, resources have to be committed to the effort. The fact is that lots of resources are being committed to the effort, But there are a bunch of shows and races going on – some big, some small – and it’s pretty much impossible to test horses at all of them. It costs money to work do drug detection; there are lots of shows; there are even more horses. Organizations like the FEI have a very aggressive “no tolerance” program for the top riders, but, in all honesty, this program applies to a very small percentage of horses, so it’s easier for them. Still, two things should be noted: 1) FEI horses do just fine under strict drugs rules (FEI competitions are very competitive and exciting, actually), and 2) Some of those people still may look for other substances to give their horses.

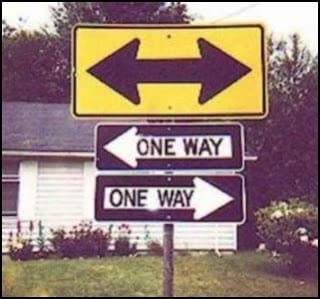

Further complicating the oversight situation is that there’s no single jurisdiction setting the rules. For example, in the United States, each state has its own rules about horse racing – ditto with show horses. Controlling medications are easier if you’re in Hong Kong, where treatments and medications are given and recorded by a handful of veterinarians, employed by the racetrack. Even show horses can come under several jurisdictions at the same time. Then there are other disciplines – like cutting and reining horses – that have little or no oversight over the drugs that go into horses.

6. Lack of direction from the top – Effective change has to come from the top down. Until judges and various equine industries stop rewarding half-dead looking hunters, sleep-walking Western Pleasure horse, and trainers stop mounting barely competent amateurs on horses they can’t ride, the use of drugs in various endeavors will almost undoubtedly continue. If the goal is to follow the money, chase points, or win ribbons, and if you can achieve those goals by means other than good horsemanship, well, why not?

6. Lack of direction from the top – Effective change has to come from the top down. Until judges and various equine industries stop rewarding half-dead looking hunters, sleep-walking Western Pleasure horse, and trainers stop mounting barely competent amateurs on horses they can’t ride, the use of drugs in various endeavors will almost undoubtedly continue. If the goal is to follow the money, chase points, or win ribbons, and if you can achieve those goals by means other than good horsemanship, well, why not?

Like I said, though, this is a multi-headed beast. It’s not just that, “Drugs are bad.” For example, is there a place for a horse with arthritis to compete if he needs a pain-relieving medication? Would it be OK to run a racehorse that’s been given a drug that’s been shown to help prevent bleeding from the lungs? I don’t pretend to have answers for questions like these. But they are questions that need to be – and are – being asked and addressed openly. Everyone who loves horses needs to make sure that the questions keep coming.