Not me

I looked at a horse for lameness a couple of weeks back. Not an uncommon thing for me to do, of course, but one that is always fraught with choices. As I was thinking about the exam, I reflected on all of the choices that I had made, and how differently the situation could have been handled in other hands, or because of demands or expectations. So, with the permission of my friend and long-time client (whose name has been changed because that’s what you do in these sorts of stories), I thought I’d through the case out there for your to think about, both in terms of how we handled the situation, what you might have liked, and the advice that you might have been given, or the things that you might have been told.

A moose. Not Moose.

“Moose” is an 18-year-old gelding of uncertain ancestry. Not that it really matters, of course – he’s a nice horse and a nice guy. He’s a thick-boned little horse, sort of a Cobb, Haflinger, run-through-a-wall-with-no-problem sort of build. The problem was that Moose had started limping on his right fore limb.

Moose’s job is very important. He takes care of his person. Carissa’s not an accomplished rider, that is, she’s not chasing ribbons or notoriety, but she loves to go out for walks on the trails. Moose loves it, too. It’s good for both of them.

Moose had been showing some lameness for a while. It hadn’t gotten any worse – it just hadn’t gotten any better. When he was asked to trot – which wasn’t that often – Carissa noted his head moving up and down, and that he felt a bit uncomfortable to ride. Nothing really seemed to help, be it a little rest, or some new shoes, or even a dose or two of a pain reliever. It was time to figure out what was going on.

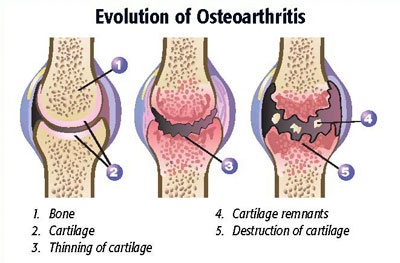

Moose was noticeably limping on his right fore limb. When Carissa trotted him, it was easy to see. The head went up when his right fore limb hit the ground and down when the left fore limb hit the ground. I could see and feel a bony bulge around his pastern, (although it wasn’t immediately obvious because his legs were pretty furry). It was obvious – to me, anyway – that Moose had “ringbone,” an old descriptive term of the sort that the horse world has used and held onto for centuries. Otherwise stated, he obviously had osteoarthritis of his pastern. I told Carissa what I thought the problem was.

Moose was noticeably limping on his right fore limb. When Carissa trotted him, it was easy to see. The head went up when his right fore limb hit the ground and down when the left fore limb hit the ground. I could see and feel a bony bulge around his pastern, (although it wasn’t immediately obvious because his legs were pretty furry). It was obvious – to me, anyway – that Moose had “ringbone,” an old descriptive term of the sort that the horse world has used and held onto for centuries. Otherwise stated, he obviously had osteoarthritis of his pastern. I told Carissa what I thought the problem was.

Carissa said, “What should we do?”

That’s really the crux of things, isn’t it? Carissa didn’t know what was wrong with Moose – I did. That’s part one of my job: finding out what’s wrong (that’s not always easy, of course). But now Carissa wants to see what can be done. This is where medicine gets interesting, where fingers get pointed, and where “right” answers often don’t exist. What can be done and what someone wants to do are often not the same.

I suppose that I could have done a nerve block on Moose to localize the lameness. Had I put some local anesthetic over the nerves that run down the leg, I’m quite confident that I could have made Moose temporarily trot without signs of lameness. Veterinarians do that sort of thing all the time. It’s a very useful technique. Although it’s somewhat imprecise, “blocking” is a reasonably effective way to determine the area from which the horse’s lameness is originating. But I was 99.9% certain I knew what Moose’s problem was. Would you have been content with that?

I suppose that I could have done a nerve block on Moose to localize the lameness. Had I put some local anesthetic over the nerves that run down the leg, I’m quite confident that I could have made Moose temporarily trot without signs of lameness. Veterinarians do that sort of thing all the time. It’s a very useful technique. Although it’s somewhat imprecise, “blocking” is a reasonably effective way to determine the area from which the horse’s lameness is originating. But I was 99.9% certain I knew what Moose’s problem was. Would you have been content with that?

I suppose that I could have done X-rays on Moose. X-rays would have shown me what my eyes already knew. The joint wasn’t normal. X-rays could have helped me determine the extent to which the joint had been destroyed by arthritis. However, I don’t think that information would have been clinically relevant. That is, knowing how much of the joint had been destroyed by arthritis wouldn’t have made any difference in treatment options. Would you have wanted X-rays?

While I knew what was wrong with Moose, I also knew that Carissa didn’t have a whole lot of money. X-rays and nerve blocks cost money. I knew Carissa worked hard to take care of Moose and that even though she would spend money to take care of him, I thought it was also my obligation to take care of Carissa, too. More money for Carissa means more money to take care of Moose. At least, that’s how I think.

While I knew what was wrong with Moose, I also knew that Carissa didn’t have a whole lot of money. X-rays and nerve blocks cost money. I knew Carissa worked hard to take care of Moose and that even though she would spend money to take care of him, I thought it was also my obligation to take care of Carissa, too. More money for Carissa means more money to take care of Moose. At least, that’s how I think.

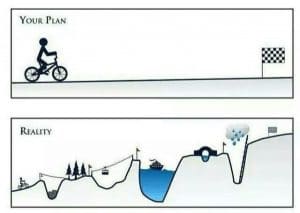

With a problem such as osteoarthritis, it’s pretty easy to go down a financial rabbit hole. The problem, medically speaking, is that osteoarthritis doesn’t have a cure. When there’s a cure, deciding on a treatment is really pretty easy. If a cure has been established, everyone knows what it is, and everyone uses it.

Horse surgery – the early days

In the case of arthritis of the pastern, there is a “cure,” at least in some sense. In some cases, the affected joint can be surgically fused. It’s an expensive option, maybe in the $10,000.00 ballpark in southern California, with something like a 65 – 75% success rate reported in the scientific literature (depending on a lot of factors). We talked about that. However, but with Moose’s age, and Carissa’s budget, surgery wasn’t an option. Plus, there are the risks of losing Moose during surgery, or surgery failing and making things worse, which were risks that Carissa wasn’t interested in taking. Beyond that, I had no cure to offer. Would you have done surgery?

However, even when there isn’t a cure, there are still plenty of “options.” Shoeing changes. Boots. Liniments. Shelves of supplements. Pain relievers. Acupuncture. Lasers. Magnets. Pulsing magnets. You probably know as many of them as I do. They all have three things in common.

However, even when there isn’t a cure, there are still plenty of “options.” Shoeing changes. Boots. Liniments. Shelves of supplements. Pain relievers. Acupuncture. Lasers. Magnets. Pulsing magnets. You probably know as many of them as I do. They all have three things in common.

- None of them can fix osteoarthritis.

- They all bring lots of promise and hope.

- They all come with very real financial costs.

To me, an option that only brings false hope, costs money, and doesn’t (can’t) deliver on its promises isn’t really much of an option at all. I think that in many cases people are happy to have them, however. When confronted with an incurable problem, some people love the feeling of being able to do something, but to me, good care doesn’t mean wasting money on ineffective things, even if they make some people feel better. We talked about lots of those things, too. Would you have wanted to just do something, even if the only thing that the something did was to make you feel good?

We talked about how letting Moose move around more might really help him. For a lot of arthritic animals, moving around really helps. In southern California, where I practice, space can be pretty limited. We do the best we can. But Moose is going to get out more – and I think that will help. There’s something that Carissa can do. It helps it doesn’t cost anything.

We talked about regular doses of phenylbutazone. For some reason, bute has becoming something of a whipping boy for hyperconcerned horse owners. There’s a pervasive fear in some circles that a horse on bute is going to have problems such as ravaged kidneys, or a devastated, ulcerated stomach. Side effects can happen, of course, but at judicious doses, they’re extremely rare. Bute’s cheap, pretty effective, and has few side effects at recommended doses. I like medicines like that. Carissa can afford it – she likes it, too. Would you?

At the end of the visit, where were we? We’d identified Moose’s problem, although we hadn’t illustrated it with X-rays. We’d come up with an inexpensive plan to help control his pain. Moose will get out more and he’ll get a couple of grams of phenylbutazone every day. He’ll mostly get ridden at the walk. He’ll probably get a bit more attention, which is probably good for Moose: Carissa, too. If walking under saddle gets to be much for him, he’ll retire to a nice pasture somewhere.

At the end of the visit, where were we? We’d identified Moose’s problem, although we hadn’t illustrated it with X-rays. We’d come up with an inexpensive plan to help control his pain. Moose will get out more and he’ll get a couple of grams of phenylbutazone every day. He’ll mostly get ridden at the walk. He’ll probably get a bit more attention, which is probably good for Moose: Carissa, too. If walking under saddle gets to be much for him, he’ll retire to a nice pasture somewhere.

There’s a lot to think about when it comes to looking at a horse for lameness: for any condition. Carissa’s happy. She understands what’s going on and she has a plan. She can afford to keep Moose and give him a nice home for a while longer. I missed out on some revenue, I suppose, but I know that I’ll see Carissa and Moose again. I’ve found that caring for both the horse and the client helps build trust. I don’t feel compelled to do everything that I can do on a single visit. The way I look at things, veterinary medicine should involve caring for everyone: the horse, my client, and me, too.

But I’m curious. Would you have been happy with this visit? Would you have felt like you should have had more? Would a bucket of this or that, or some sort of device have made you happier? There’s nothing wrong with feeling that way – many times there’s no “right” way and feeling like you’re doing something might help overcome a feeling of helplessness. But there’s cost for that, too.

As much as I wish it could be easy, horse medicine’s complicated. I think things were handled just about right. What do you think?