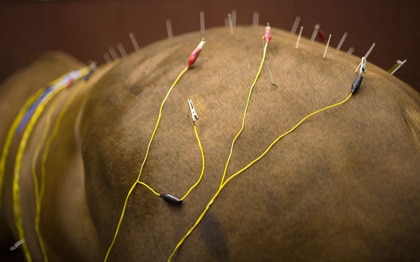

Every so often you see articles in magazines, or your run across websites, that extoll the virtues of acupuncture. Just to be clear, what I’m calling “acupuncture” involves sticking thin needles into horses at spots (“points”) that are said to be unique – heck, you’re even supposed to need special training to find them – for the purposes of treating this, that, or the other. It’s usually promoted as being one of those therapies that’s “alternative” or “natural” or “complementary” or “traditional,” among other, generally positive, adjectives. It’s said to be an “option” for helping the horse cope with a myriad of problems.

Personally, and in case you didn’t already know, I think it’s all a waste of time and money. And, to a certain extent, so does the American Veterinary Medical Association – in May 2016, they denied specialty status to the practice, based on a lack of science, among other things.

NOTE: None of this is because I – or anyone – is “against” acupuncture. That would be stupid. I mean, I got into horse medicine for one reason, and one reason only: because I want to help horses. I’m for anything that does that. It would be totally against everything I went to vet school for to be otherwise.

That said, therapies matter. They matter for a lot of reasons. Here are two. First, you probably want to spend your money wisely, and not waste it. Second, you probably don’t want to annoy your horse with a treatment that’s unnecessary, and especially so if it doesn’t do anything.

Anyway, if you’re a reasonable thinker, hopefully, you’re going to ask, “Why do you think that [acupuncture is a waste of time and money]?”

Here’s why.

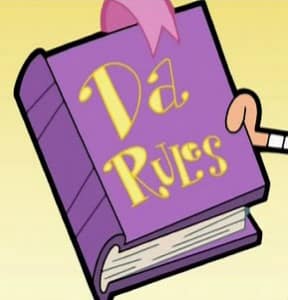

GROUND RULES – For me to think much of a therapy, I’d like for it to satisfy four simple ground rules.

GROUND RULES – For me to think much of a therapy, I’d like for it to satisfy four simple ground rules.

1. People should tell the truth about it.

2. It should have an accepted way that it works (at least eventually), and a way that makes sense.

3. It should have a few specific conditions for which it is useful.

4. There should be a strong, and, over time, a growing, body of evidence supporting it.

So, if you buy into those premises, acupuncture is very consistent. It fails on all four counts. Here’s how.

1. PEOPLE SHOULD TELL THE TRUTH. I mean, really, this one is kind of obvious, right? But, when it comes to acupuncture, proponents haven’t been very truthful.

a. Acupunture points have not been shown to exist in the horse’s body (or in anything else’s body). Acupuncture enthusiasts contend that there are specific points on the horse’s body that respond to attention. They even have names, such as “Stomach 36” or “Governing Vessel 1.” The truth is, they can’t be shown to exist, that is, there’s nothing about “points” that are different from any other  “point” on the horse’s body. There’s nothing identifiable that makes an acupuncture point unique. An anatomist could very easily identify a nerve, or a fetlock, or a mane; they exist. Not so with “points.”

“point” on the horse’s body. There’s nothing identifiable that makes an acupuncture point unique. An anatomist could very easily identify a nerve, or a fetlock, or a mane; they exist. Not so with “points.”

Acupuncture points are more like the dots on a map. Try as you may, when you travel to the big-red-dot-on-the-map that is Cleveland, Ohio (if you ever travel to Cleveland, Ohio), once you get there, you won’t find a big red dot. Everyone agrees that the place that you just went to is Cleveland, Ohio, the signs say it’s Cleveland, Ohio, but, really, there’s nothing inherent to any of the streets, buildings, or fire hydrants that would identify them as uniquely “Cleveland.” But at least residents have put up signs, so you can be pretty sure you’re there (say, to visit the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame).

Or, to put things more succinctly, as stated by Felix Mann, a founder of the British Acupuncture Society: “…the acupuncture points are no more real than the black spots that a drunkard sees in front of his eyes.” (Mann, F. Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine. Butterworth Heinemann, London, 1996, p. 14)

b. Acupuncturists don’t find individual “points” in the same locations. Even though there’s no such thing as a big red dot imbedded in the ground that is Cleveland, everyone agrees on where it is. However, if you get a group of acupuncturists together, they can’t seem to agree on where points are. There have been several studies that have shown that when you ask group of acupuncturists to identify a particular point on a particular body, that “point” turns out to be pretty darn big – on the order of 40 square centimeters in some cases.

NOTE: Forty square centimeters is pretty big – a bit more than six square inches. Hard to conceive of such a thing as a “point,” unless, say, you consider a coffee spill on your shirt to be a “point” of coffee.

So, even though acupuncture points don’t exist, people can’t seem to pinpoint them in the same spot anyway. Here, as elsewhere, two wrongs do not make a right.

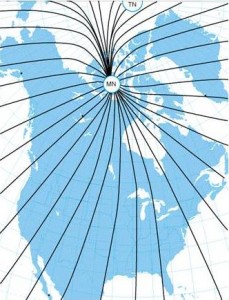

c. “Meridians” have not been shown to exist. According to many acupuncture enthusiast, the “points” are linked along channels. These channels are more commonly called “meridians,” a term that was co-apted from the field of geography in the 1930’s by a Frenchman who was writing – quite inventively, as it turns out – about Chinese medicine.* To extend the analogy, “meridians” are the lines on the map that connect Cleveland and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (which also exists). However, much like acupuncture points, and much like the map lines, nobody has shown that such things as “meridians” really exist.

What’s even more curious is how the “meridians” got onto (into?) horses in the first place. Turns out they were “transposed.”

NOTE: At this point, I feel somewhat compelled to point out that, as writer Dave Barry often notes, “I am not making any of this up.”

At some point in time, some folks took one of the myriad human acupuncture charts – charts that also don’t necessarily agree on anything – and laid it down (transposed it) on a horse. Back in the 1980’s, an acupuncturist looked at a “traditional” chart and a “tranpositional” chart and didn’t find any points of agreement. But there you go, that’s how “meridians” got onto horses. It’s also why horses have a “gall bladder meridian,” even though horses don’t have a “gall bladder.”

If you are getting a headache, remember one thing. When it comes to acupuncture, sometimes it helps not to think too hard.

d. Acupuncture isn’t old, and isn’t part of the Chinese tradition of treating horses (or any other species, for that matter). I don’t want to belabor this point, since I’ve written extensively about it, but the Chinese didn’t do anything to horses that even remotely resembles modern acupuncture. Personally, I think that acupuncture enthusiasts should stop saying that they did, but it’s become part of the sales pitch. Still, it’s not the truth, and that bothers me.

2. IT SHOULD HAVE AN ACCEPTED WAY THAT IT WORKS. When treatments have an effect on the body, there’s a reason. People may not know the reason initially, but they figure it out pretty soon. Interestingly, anesthesia gases are a good example of not knowing how something works, by the way, but they are figuring it out, and nobody doubts that they work.

Not so with acupuncture. There are lots of complicated reasons that have been proposed for any effects. Some folks invoke mystical “energies” (the Chinese called it qi, but mystical energies have been said to exist by almost every culture). Others say that it releases body chemicals called endorphins.** Others – less enthusiastic about needling – say it’s simply a placebo, or a diffuse noxious stimulus.*** Regardless, it’s been many decades, and proponents don’t have a convincing explanation for how acupuncture “works” (assuming it works at all). To me, that’s a problem.

3. IT SHOULD HAVE SPECIFIC CONDITIONS FOR WHICH IT IS USEFUL. Nothing treats everything. Specific treatments treat specific conditions. You usually don’t give a horse antibiotics if it’s limping. You don’t put a horse with colic on eye medication. However, acupuncture seems to be good for just about everything.

3. IT SHOULD HAVE SPECIFIC CONDITIONS FOR WHICH IT IS USEFUL. Nothing treats everything. Specific treatments treat specific conditions. You usually don’t give a horse antibiotics if it’s limping. You don’t put a horse with colic on eye medication. However, acupuncture seems to be good for just about everything.

Here’s a list, from a website offering acupuncture. “Acupuncture is an excellent modality for relieving musculoskeletal pain, obscure lameness, back pain and decreased performance. Acupuncture can also be very effective for GI problems, hormone/metabolic disease, behavioral issues, neurological disorders, heaves (RAO, COPD) and prevention of disease – just to name a few!”

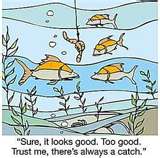

I mean, really? Here’s a tip. If something is said to be good for everything, in fact, it’s probably not good for much of anything. Otherwise stated, if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

4. THERE SHOULD BE A STRONG, AND, OVER TIME, A GROWING BODY OF EVIDENCE SUPPORTING IT.

So, imagine that you’re working for a company. You tell your boss, “I’m working on something that’s really promising. I think that this is really going to be something. I just need some more time.”

And it’s been, say, 50 years.

What would you expect your boss to say? What would happen to your project?

Acupuncture is like that, too. There was a time when it was possible to say, “There isn’t enough research.” But that time is past. There are now thousands of studies (some good, many more bad). There are more studies on acupuncture on And, after all that time – and all that money – no one can say if it really helps for any condition of the horse (or any other species, for that matter).

If a therapy really is effective, people figure it out pretty quickly, even if the idea was initially controversial (say, like bacteria being a part of the gastric ulcer problem in people). In a pretty short time, if something is effective, people can reproduce it and refine it. Pretty soon, most everyone is doing it, for specific purposes.

But with acupuncture, we still have “controversy.” To enthusiasts, it’s still “promising.” But, really, it’s not. Actually, acupuncture seems to be just an empty promise.

So that’s why, in my opinion, there’s just very little reason to bother with acupuncture. You’re probably not going to hurt your horse if you get pins stuck in him, but, to me, medicine should be more than just providing stuff that doesn’t hurt: you’re supposed to give something that helps (and especially if you’re being asked to spend money on it). Acupuncture hasn’t proven itself to be a useful therapy in five decades or so – the AVMA didn’t grant specialty status because of that very reason. In my opinion, there’s really no reason to expect that it’s ever going to happen.

*************************************************************************************************************************************

* In geography, a meridian means, “A circle of constant longitude passing through a given place on the earth’s surface and the terrestrial poles.” In acupuncture, it means, “These points that don’t exist are linked up with a line that also doesn’t exist.”

** Turns out that there are lots of ways to raise endorphin levels in horses. Lunge them – or jump them over a fence. Put them in a trailer (or an airplane). Put a twitch on their nose. Make them colic (I don’t recommend this, but colic does raise endorphin levels).

*** If you have a headache, and someone kicks you hard in the shin, your head may not hurt as much, at least for a bit.