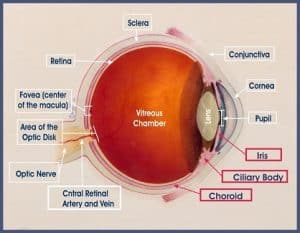

Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU, or, if you want to go way back, “moon blindness,” because it was said to come and go with the phases of the moon) is one of the most serious and frustrating problems affecting the horse’s eye. Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea; the uvea, if you didn’t know, is the layer of the eye that has pigment, just below the cornea. All mammals have uveas. You’ve a uvea; I’ve a uvea.

Equine recurrent uveitis (ERU, or, if you want to go way back, “moon blindness,” because it was said to come and go with the phases of the moon) is one of the most serious and frustrating problems affecting the horse’s eye. Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea; the uvea, if you didn’t know, is the layer of the eye that has pigment, just below the cornea. All mammals have uveas. You’ve a uvea; I’ve a uvea.

The uvea is made up of the Iris, Ciliary Body, and the Choroid, at the front of the eye.

Uvieitis is a nasty disease. It’s characterized by episodes of inflammation (that you may not even be aware of), followed by quiet periods where nothing seems to be happening. Inflammation can occur in the front or the back part of the uvea, but such distinctions, while a really big deal for people that study horses’ eyes, don’t really make much difference when it comes to management of uveitis cases, so we’re not going to talk out them. Uveitis can be hard to manage and, because of the persistent inflammation, and the permanent secondary changes that occur because of that inflammation, it’s also the leading cause of blindness in both eyes of the horse. We’re going to talk about risk factors here, because if you know the risk factors, it might help you recognize the problem earlier, when it’s more amenable to treatment.

WHAT ARE THE SIGNS OF UVEITIS?

Uveitis can present with a lot of different signs, all of which occur because of inflammation (inflammation is the “itis” part of uveitis). These include:

- Spasm of the eyelid

- Tearing

- Sunken eye

- Light sensitivity

- Redness of the membranes of the eye

Uveitis in an Icelandic Horse. By Christian Muellner – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24340693

None of these signs are specific for uveitis – they can occur with any sort of eye inflammation. However, if you see your horse squinting or tearing, or if his eye is all red, it’s certainly a good reason to have your veterinarian take a look. And to make things even more difficult, when uveitis occurs in the back of the uvea, at first, you may not se any signs at all.

Over time, inflammation in the horse’s eye leads to all sort of bad things, from swelling in the cornea (the clear covering on the front of the eye) to detachment of the retina (at the back of the eye, which has the nerve endings that allow your horse to see). When the cornea swells, the surface of the eye turns blue, which is a sign that most people don’t miss. Secondary changes such as glaucoma (increased eye pressure) can set in, as well. Ultimately, non-stop inflammation destroys the eye and causes blindness.

WHAT CAUSES UVEITIS?

Uveitis is complex. That’s a real problem, because the more complex a medical problem is, the harder it is to understand and the more difficult it is to deal with. Regardless, there are many environmental and genetic factors that can start off a case of uveitis. For example, uveitis been associated with gastrointestinal and orthopedic disease in some horses.

Uveitis is complex. That’s a real problem, because the more complex a medical problem is, the harder it is to understand and the more difficult it is to deal with. Regardless, there are many environmental and genetic factors that can start off a case of uveitis. For example, uveitis been associated with gastrointestinal and orthopedic disease in some horses.

The primary underlying problem is caused by the horse’s immune system. In fact, horses are considered to be a good model for trying to understand immune-related problems in all species (not that this is a good thing). After some sort of sensitizing episode, say, from the horse’s environment, or because of some genetic risk factor(s), immune factors (antibodies) get activated and start to act against proteins in the horse’s eye. Uveitis is an “auto-immune” disease, that is, the horse’s immune system turns against itself.

INFECTIOUS RISK FACTORS

Armi (left) and Auden (right), who also don’t have uveitis.

Bacteria from the genus Leptospira have been commonly fingered as an underlying cause of uveitis, not only in horses, but in people, dogs, and other mammals, too. But it’s not just Leptospira, other bacteria, as well as parasites and viruses have also been associated with uveitis. There may even been other environmental risk factors, but we don’t really know enough about them yet. These can be a real bugger to try and diagnose because the cause of the infections doesn’t always show up on blood tests. They do show up if you take fluid from the eye, but that’s not a test that anyone does because it’s invasive and fraught with it’s own problems (like causing eye inflammation).

Still, although there are conflicting studies, Leptospira does seem to be a real problem, when it comes to uveitis. Horses with evidence of leptospirosis (from blood tests) seem more likely to become blind than horses that develop uveitis from other causes. Horses that live in river valleys, or in other areas where Leptospira is prevalent are at risk of developing infections during wet periods and are therefore at a higher risk of developing uveitis.

Rhodococcus equi, a bacteria that primarily causes respiratory infections in foals, can also cause uveitis. This has also been shown experimentally in foals that were inoculated with the R. equi bacterium. Foals with R. equi caused by uveitis can recover with their vision intact, but no one has yet done a study following up to see if these babies went on to develop uveitis as adults.

Borellia burgdorfi, that bacteria associated with Lyme disease, has also been associated with uveitis (adding another group of worms to an already very full can). Still, given the fact that many horses are known to be exposed to Borellia, very few of them seem to develop laminitis, so the risk of developing uveitis from Lyme Disease doesn’t seem to be all that high, unless the horse is showing more severe signs of disease.

Borellia burgdorfi, that bacteria associated with Lyme disease, has also been associated with uveitis (adding another group of worms to an already very full can). Still, given the fact that many horses are known to be exposed to Borellia, very few of them seem to develop laminitis, so the risk of developing uveitis from Lyme Disease doesn’t seem to be all that high, unless the horse is showing more severe signs of disease.

Several parasites have been associated with uveitis, however, uveitis secondary to parasite infection (such as Onchocerca sp.) also appears to be really rare. That’s because in order to cause uveitis, the parasites have to infiltrate the eye itself. It can happen – it’s just not common.

Viral infections such as equine influenza, equine viral arteritis (EVA) or equine herpes virus (EHV) are suspected possible causes of uveitis. In particular, EHV has been shown to be able to infect the tissues of the eye. Still, even though an association has been suspected for years, it’s not clear if viruses can actually cause uveitis in horse eyes.

NON-INFECTIOUS RISK FACTORS

Age appears to be a risk factor for uveitis – it’s most commonly recognized in horses around 12 years of age (although it certainly could have started well before the problem was recognized). Some studies have suggested that geldings get uveitis more commonly than mares, however, other studies have not supported that association.

It doesn’t seem like management factors are associated with the development of uveitis. In humans, diet, obesity, activiy levels, and the microbiome (the bacteria in the gut) have NOT been associated with uveitis, although, as with so many conditions, more investigation is still needed.

It doesn’t seem like management factors are associated with the development of uveitis. In humans, diet, obesity, activiy levels, and the microbiome (the bacteria in the gut) have NOT been associated with uveitis, although, as with so many conditions, more investigation is still needed.

Vaccines are often said to cause uveitis. It makes some sense to be suspicious – after all, vaccines do cause the horse’s body to mount an immune response – but a recent study in the UK wasn’t able to make any association between vaccines and the development of eye problems.

As for environmental risk factors, the study that failed to find an association between vaccines and uveitis did identfy two: turnout in a recently flooded pasture and proximity to a pig farm. While I can confidently say that I’ve never come across either situation in southern California, if you live next to a pig farm with flooded pastures, it might be best to keep your horse somewhere else. In fact, if it were me, and if that were my neighborhood, I might consider moving altogether.

GENETIC RISK FACTORS

Knabstruppers

There do appear to be risk factors for certain breeds to develop uveitis. In particular, Warmbloods, Appaloosas, and Icelandic horses seem to be overrepresented as at-risk breeds. Other patterned breeds with leopard spotting (say, Knabstruppers), seem to have a higher incidence of uveitis compared to other breeds, as well.

The problem with genetic predisposition, of course, are two-fold. First, you can’t do anything about it. By the time the horse that you want (or will eventually want) has been born, his genetics have already been established. Second, a genetic risk is not an ironclad guarantee that something is going to happen. So, if you’ve always had your heart set on a Knabstrupper, I think you should probably just go get one (unless his eyes are tearing, cloudy, or painful, of course).

TO SUM IT UP

Neale, the subject of everyone’s admiration

Uveitis is a big problem in horses (as well as in other mammalian species). We know that it’s an immune mediated problem. We know that it involves a breakdown of the normal barrier that exists between the eye and the blood circulatory system.

Fortunately, for many horses, uveitis doesn’t turn into a constant problem. Horses that have a normally functioning immune system should be able to use their body’s normal healing mechanisms to make uveitis a one-time event. But for others, the healing mechanisms don’t work well, or don’t work at all, and chronic uveitis – and blindness – is the result. There’s more research coming: just not fast enough.

I’ll write about treatment in another article – it’s mostly about trying to do everything you can to stop the inflammation that’s going on in the horse’s eye. But hopefully, you now have a bit more understanding of what causes this very difficult problem.