Lyme, Connecticut looks to be a beautiful spot (I’ve never been there). Lyme is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 2,406 at the 2010 census. It’s just up Highway 156, not far from where the Atlantic Ocean meets the US. Right next to Old Lyme. And the two towns gave their name to one of the more frustrating diseases of horses.

Lyme, Connecticut looks to be a beautiful spot (I’ve never been there). Lyme is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 2,406 at the 2010 census. It’s just up Highway 156, not far from where the Atlantic Ocean meets the US. Right next to Old Lyme. And the two towns gave their name to one of the more frustrating diseases of horses.

Let me start off by saying that I’m am exceedingly glad that I don’t have to treat horses with Lyme Disease because, so far, it seems not to have made its way into southern California, at least, not so anyone would notice. But I’ve certainly heard and read all about it. And in an effort to learn more, I sat in on a 90 minute seminar on Lyme Disease on December 8, 2015, at the 61st annual AAEP meeting in Las Vegas, NV, led by internal medicine specialists Drs. Joe Bertone, of Western College of Veterinary Medicine, and Amy Johnson of the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center, and attended by about 100 colleagues who DO have to treat the problem (all of whom have my sympathies). I thought I’d share with you what I learned.

WHAT CAUSES LYME DISEASE?

Let’s start with some basic stuff. Lyme Disease is caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi. The baterium is spiral shaped when you look at it under a microscope – probably not nearly as much fun as it sounds – and the spiral shape gives it a classification. It’s called a spirochete, just like the bacterium that causes syphilis, facts which, come to think of it, are almost completely unimportant. Anyway the disease is transmitted through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks.

Let’s start with some basic stuff. Lyme Disease is caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi. The baterium is spiral shaped when you look at it under a microscope – probably not nearly as much fun as it sounds – and the spiral shape gives it a classification. It’s called a spirochete, just like the bacterium that causes syphilis, facts which, come to think of it, are almost completely unimportant. Anyway the disease is transmitted through the bite of infected blacklegged ticks.

That’s the first important thing. Lyme Disease is spread by an arthropod (technically, it’s not an insect) – the tick. And because it’s spread by ticks, it’s essentially impossible to get rid of the disease. The Center for Disease has a great little FAQ sheet on the life cycle of hard ticks, including the one’s that spread Lyme Disease.

CLINICAL SIGNS

The clinical signs of horses that affected with Lyme Disease are really vague. And that’s a big part of the problem with the disease. Diseases are a lot easier to understand and recognize when they have typical signs. So, for example, it’s usually not hard to recognize horses with colic because they lie down, roll around, stop eating: that sort of thing. Lyme Disease, on the other hand, has signs that don’t really stick out. The signs may include things like generalized stiffness, joint swelling (less common), extreme sensitivity to being touched (called “hyperesthesia”), lameness that shifts from leg to leg, loss of muscle tone, slight fever (less common), weight loss, and poor performance. Really bad cases can get nervous system disease, or serious eye problems (or both).

UNCOMFORTABLE ASIDE: You can immediately start to see part of the problem with Lyme Diseases here. I could write this article about Equine Protozoal Myelitis. And I might say, “The signs may include things like generalized stiffness…” I could probably writhe this article about gastric ulcers and say they same thing. Come to think of it, I did write articles on those problems. But the problem is that horses can show vague clinical signs from all sorts of conditions, and for all sorts of reasons. In fact, some of those horses can even be normal, and just be having a bad day or two. Which means that some normal horses can get diagnosed with the disease, get treated, and get better, even though they never had a problem in the first place (which happens quite a bit in the horse world, actually).

CONFIRMING A DIAGNOSIS (OR NOT)

Anyway, let’s say that you’ve got a horse that’s doing something that concerns you, and you’re living in an area where Lyme Disease is prevalent (you can CLICK HERE to see tables of where Lyme Disease occurs in the US, and be happy if you live in Colorado or Hawaii (there are other reasons to be happy for that, too), but less so – insofar as Lyme Disease goes – if you live in Maine or Vermont. Well, what then?

Here’s where things start to get really messy. If Lyme Disease is a possible concern, your veterinarian is probably going to want to run a test – and there are several – to see if your horse has developed an immune response to the disease. The tests measure levels of antibodies; an measure of antibody levels is called a titer.

There are several tests, including one developed at Cornell University – right in the heart of Lyme Disease country – which you can read about it you CLICK HERE (and there’s lots of other good information, too). The way these tests work isn’t particularly important unless you’ve got a keen interest in immunology, and they are certainly useful, but there are some unsettling facts about them.

- None of these tests can actually tell you if the bacterium is causing your horse’s problem

- There may be other strains of the bacterium that we don’t know about, and the tests won’t pick them up

- The magnitude of the titer has nothing to do with clinical disease. Otherwise stated, you can’t tell how bad the infection is by the horse’s titer, and it’s pretty hard to tell if the horse is getting better by his titer once you start treatment.

- You can get false positives. That is, a horse can text positive, and not have the disease. Dr. Bertone showed this when he took blood from ponies in the middle of the California desert – no hotbed of Lyme Disease, for sure – and still found positive tests.

UNCOMFORTABLE ASIDE #2: You can have a horse with vague clinical signs suggestive of Lyme Disease and a positive test, and your horse may not have Lyme Disease.

UNCOMFORTABLE ASIDE #2: You can have a horse with vague clinical signs suggestive of Lyme Disease and a positive test, and your horse may not have Lyme Disease.

OH, AND YOU PROBABLY DON’T NEED TO BOTHER TESTING HORSES THAT ARE OTHERWISE NORMAL: If a horse is otherwise normal, a positive test for Lyme Diseae means, well, who knows? And some people are apparently running Lyme Disease tests as part of a prepurchase exam. That might make some sense if the test were really accurate, but Dr. Johnson says that if a horse is normal on a prepurchase exam, there’s no point in running at test for Lyme Disease, because it won’t tell you anything useful. Save your money.

WHAT ABOUT TREATMENT?

Anyway, as it turns out, you can have this horse that you’re worried about, that has a positive test, and you decide to treat it. The next questions are, “With what?” And, “For how long?” Here, answers are perhaps a bit more clear, but not without there own problems.

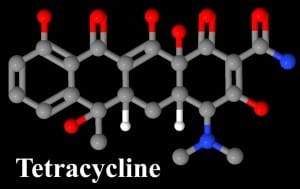

Mostly, people use antibiotics from the tetracycline class, although another antibiotic, ceftiofur sodium, sold as Naxcel®, can also be used. Tetracyclines are a large group of antibiotics with a molecular structure containing four rings: hence, “tetra,” which is from Ancient Greek for “four.” So, your horse can get tetracycline in the vein, in pills, in capsules, or in powder; ceftofur is given in the muscle. Treatment recommendations are usually that the horse gets medicated for 30 – 90 days, depending on how he responds. And, of course, there are problems (hey, this is medicine, you know).

Mostly, people use antibiotics from the tetracycline class, although another antibiotic, ceftiofur sodium, sold as Naxcel®, can also be used. Tetracyclines are a large group of antibiotics with a molecular structure containing four rings: hence, “tetra,” which is from Ancient Greek for “four.” So, your horse can get tetracycline in the vein, in pills, in capsules, or in powder; ceftofur is given in the muscle. Treatment recommendations are usually that the horse gets medicated for 30 – 90 days, depending on how he responds. And, of course, there are problems (hey, this is medicine, you know).

- The medications can cause problems, especially intestinal problems

- Horses may not eat them (powder or pills or capsules)

- Daily IV dosing is a pain, and veins don’t like getting needles in them every day

- It’s expensive

- Tetracyclines have anti-inflammatory effects that may help certain conditions that aren’t Lyme Disease

- If you medicate your horse for Lyme Disease, and he doesn’t have it (possible), he might get better anyway, which really confounds things

So how long do you treat? You treat until the horse seems better. The antibody tests aren’t a good way to monitor the response to treatment – in fact, the antibody levels in some horses go up with treatment. If you think that your horse has Lyme Disease, you just have to treat – and see how it goes.

So how long do you treat? You treat until the horse seems better. The antibody tests aren’t a good way to monitor the response to treatment – in fact, the antibody levels in some horses go up with treatment. If you think that your horse has Lyme Disease, you just have to treat – and see how it goes.

And here’s some more sobering news. If a horse has a really bad case of Lyme Disease – if it’s affected in the eyes, or if it has nervous system problems – treatment probably isn’t going to help. If the disease becomes chronic, immune responses may not even happen, particularly if the problem is localized. And you may not even know if your horse really had Lyme Disease until a post-mortem exam is done.

WHAT ABOUT VACCINATION?

A very reasonable question. Vaccination is, after all, one of the most important advances in the history of medicine, and, for certain diseases, they work very well. However, there’s no vaccination against Lyme Disease that has been approved for horses. There are a couple for dogs, however, and one of them has been tested in horses (it’s called Recombitek®). When 2 vials are given under the skin, three weeks apart, a good immune response can be measured. Which is fine, however:

A very reasonable question. Vaccination is, after all, one of the most important advances in the history of medicine, and, for certain diseases, they work very well. However, there’s no vaccination against Lyme Disease that has been approved for horses. There are a couple for dogs, however, and one of them has been tested in horses (it’s called Recombitek®). When 2 vials are given under the skin, three weeks apart, a good immune response can be measured. Which is fine, however:

- It’s pretty expensive.

- Nobody know what immune levels are protective against Lyme Disease

- After the initial series, the vaccine has to be repeated every six months

So, right now, with no approved vaccine for horses, and no real information to confirm that the canine vaccine works in horses, it’s sort of like, “You pays your money and you takes your chances.”

I HAVE TO TELL YOU THIS: The first time the saying about paying money and taking chances saw print was in an 1846 Punch Magazine from the UK. A cartoon entitled ”The Ministerial Crisis” has a showman telling a customer, ”Which ever you please, my little dear. You pays your money, and you takes your choice.” You can look it up!

WHAT ABOUT OTHER KINDS OF PREVENTION?

Honestly, that would be the best thing of all. And tick prevention is pretty easy, if you live in the desert, with no trees, no deer, and no moist places for ticks to live and reproduce. But if you’re in a forested area, or a place with deer, or an area with stalls and warm bedding – like, say, the entire Northeastern United States – it’s essentially impossible to get rid of ticks. You can move to a place where there aren’t ticks, but moving is not always the easiest thing. You can use various tick sprays, and you should certainly keep the stall clean, and there are pour-on tick repellants, and you can and should try to control brush around horse pastures, but the fact is that these are very hardy parasites. But every little bit helps, I think. Here’s a link to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s information on stopping ticks.

BOTTOM LINE?

When it comes to Lyme Disease, I think that you’re best to trust experienced practitioners in your area. They have to deal with it all the time, and they have good strategies for recognition and treatment that have worked well for them. I’m writing to point out mostly that Lyme Disease is a big pain in the backside – just like it is in human medicine. Ultimately, I think that veterinarians will get to the bottom of Lyme Disease. But for now, it’s a really frustrating problem.