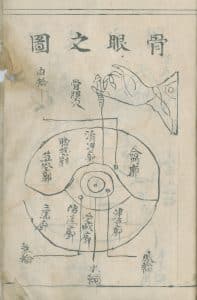

I want to introduce you to something quite rare and quite wonderful. It’s an illustration from a hand-written manuscript on Chinese Horse Medicine that I owned, written several hundred years ago.

I want to introduce you to something quite rare and quite wonderful. It’s an illustration from a hand-written manuscript on Chinese Horse Medicine that I owned, written several hundred years ago.

Marvelous, isn’t it? It’s a work of art, and a it’s a rare bit of evidence of the actual practice of medicine on horses in China. The “traditional medicine” of China, as it were.

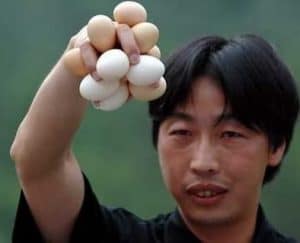

What do you see? Do you see the Chinese characters throughout the page? What’s that in the center? And above all, what’s in the hand that appears at the top of the page? Do you know? Can you guess?

Did you guess acupuncture? Could that be a needle? Doesn’t a needle mean acupuncture? And doesn’t that make acupuncture a really old practice of Chinese veterinary medicine?

ANSWERS

- It is a needle

- No, a needle doesn’t mean acupuncture

- No, acupuncture is not a really old practice of Chinese veterinary medicine

Let’s talk a bit about this amazing piece of history (I love history). And then let’s talk about something that I really don’t like, that is, what’s been done to a fascinating area of veterinary medical history.

First, let’s talk about what I love

Of course, the illustration is amazing, but it’s the text that tells us what’s on the page. The illustration shows the old Chinese treatment for a condition that they referred to as, “Bone eye.” Can you guess what that is?

If you guessed, “cataract,” you’d be absolutely 100% right. A cataract is a medical condition of the eye that’s characterized by the lens – the structure that focuses light on the back of the eye – becoming opaque. In a horse with a cataract, the lens turns white: white like a bone. Hence, “Bone eye!”

Cataracts can happen for many reasons, and some kinds of cataracts are worse than others. They can also cause other problems for the horse’s eye, such as glaucoma, which is an increase in the pressure inside the eye. When they become advanced, cataracts result in blurred vision, and can ultimately result in blindness. They can be very difficult to treat in some cases.

Fortunately, cataracts are not a particularly a common condition of the horse, but they are most commonly seen in two settings:

- Really young foals due to developmental or heritable causes (congenital cataracts). No one’s quite sure why these happen. They could be due to some developmental abnormality, or they could be genetic.

- Adult horses. Cataracts are more common in older horses, and they often occur after other diseases, such as equine recurrent uveitis (“moon blindness”). Trauma to the eye can also be a cause.

Some horses – especially the youngsters – can be successfully treated. How they’re treated depends on the kind of cataract, how big it is, and what you plan on doing with the horse. If they’re little, a cataract may not need to be treated at all. Big ones – the ones that interfere with vision, may not need treatment at all. The only way to get rid of a cataract is to take it out and put in an artificial lens, but it’s not an easy procedure: it’s one that’s best handled by a veterinary ophthalmologist. Surgery tends to be more successful in foals than it is in older horses: success rates in foals approach 85% in terms of keeping vision in the affected eye. The success rate in older horses is less because many of the older horses also have other problems that surgery simply can’t fix. Even after a successful surgery, most horses won’t have normal vision, but they seem to figure it out.

Some horses – especially the youngsters – can be successfully treated. How they’re treated depends on the kind of cataract, how big it is, and what you plan on doing with the horse. If they’re little, a cataract may not need to be treated at all. Big ones – the ones that interfere with vision, may not need treatment at all. The only way to get rid of a cataract is to take it out and put in an artificial lens, but it’s not an easy procedure: it’s one that’s best handled by a veterinary ophthalmologist. Surgery tends to be more successful in foals than it is in older horses: success rates in foals approach 85% in terms of keeping vision in the affected eye. The success rate in older horses is less because many of the older horses also have other problems that surgery simply can’t fix. Even after a successful surgery, most horses won’t have normal vision, but they seem to figure it out.

But back to our illustration. I just think it’s amazing that the Chinese – and other cultures from ancient times, including the Romans, Indians, and Greeks – carried out cataract operations. Today’s cataract surgeries are pretty straight forward; it’s a fairly quick surgical procedure done under general anesthesia. For the Chinese, the technique was also apparently pretty straight-forward: needles were inserted into the eye. Can you imagine?

But back to our illustration. I just think it’s amazing that the Chinese – and other cultures from ancient times, including the Romans, Indians, and Greeks – carried out cataract operations. Today’s cataract surgeries are pretty straight forward; it’s a fairly quick surgical procedure done under general anesthesia. For the Chinese, the technique was also apparently pretty straight-forward: needles were inserted into the eye. Can you imagine?

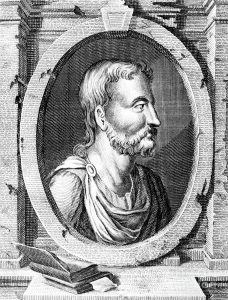

According to the Roman author Celsus (to the left), “A needle is to be taken, pointed enough to penetrate, yet not too fine, and this is to be inserted straight through the two outer tunics.” Sometimes, a good thwack in the head was used to try to help dislodge the cataract. At least for the Romans, the needle was usually sharp on one end, and heated on the other; a hot needle allowed the surgeon to cauterize the wound, and stop the bleeding. And all without the use of anesthesia… which is probably at least one reason why you never hear anybody longing for the “good ol’ days” of pre-anesthetic cataract surgery.

If you really find this old surgical history stuff cool (like I do), check out this, from PBS video. With ancient cataract surgery, the results weren’t always pretty. In this episode of Gross Science, you can learn a bit about the history of cataract surgery, and the safer and more effective methods that doctors (including veterinarians) use today.

So, to sum this all up, the manuscript page is evidence of a really fascinating piece of history about a very real condition (cataracts) that occasionally affects horses. It’s history, it’s medicine, and it’s even pretty artistic. It’s also good evidence for the transmission of medical practices that occurred between ancient cultures (otherwise stated, Chinese medicine was NOT developed in a vacuum).

Now, let’s talk about what I don’t like so much

I suppose I could have just stopped, but I’ve devoted a good bit of time to the study of the veterinary medicine of China. It’s been sort of a hobby, and one that’s been assisted by some of the most well-known scholars in the field of Chinese Medical history, such as Paul Unschuld, Paul Buell, Tim May, (and several others). I’ve even had work published in historical journals. I mean, you have to do something with your spare time, right?

What I don’t like so much is how the fascinating history of the veterinary medicine of China has been pretty much buried by misinformation from a small subset of people advocating for what they say is, “Traditional Chinese medicine.” In fact, modern day “traditional” Chinese medicine has little or nothing to do with how the Chinese traditionally practiced medicine. That’s one reason why I wrote an article – “Traditional” Chinese Veterinary Medicine – A Modern Fairy Tale – about the fallacies, distortions, and misinterpretations that advocates of their own idiosyncratic approaches use to promote their own agenda. The illustration for the treatment of “Bone Eye,” is a good example of what the Chinese really did – calling it “acupuncture,” as many have done, with similar drawings, is quite simply wrong.

NOTE: The topic of how well – or if – modern “traditional” therapies work is another discussion entirely. That will be another article or two or three, I’m sure.

NOTE: The topic of how well – or if – modern “traditional” therapies work is another discussion entirely. That will be another article or two or three, I’m sure.

Be glad your horse didn’t live in the China of 400 years ago and that he didn’t have a cataract. Treatment would have been awful, and almost guaranteed to fail (just like in every other culture). But isn’t the history of veterinary medicine cool? At least we should try to get it right, don’t you think?