Your horse’s piaffes have pfizzled. His slides have slid. His rollbacks have rolled back. His leads aren’t changing.

Your horse’s piaffes have pfizzled. His slides have slid. His rollbacks have rolled back. His leads aren’t changing.

Almost reflexively, someone will say, “Maybe he needs his hocks injected.”

Maybe he does. But maybe it’s a lot more complicated than that. At least it should be.

FIRST ASIDE (of several): It’s a little odd, statistically speaking, to think that the first thing that might be wrong with a horse is something to do with his hocks. Something along the lines of 70% of all equine lameness involves the front feet. So, if you want to look like a lameness savant, and if you enjoy meddling in other peoples’ business, you should always say, “Maybe he’s got something wrong in his front feet” and then allow that it could possibly be something else. You’ll look like a genius more often.

SECOND ASIDE: Probabilities aside, when people say, “Let’s do hock injections,” my immediate thought is, “Which joint?” The horse’s hock isn’t a single joint. The hock is made up of 10 bones and four major joints (you can look the names up if you’re really into anatomy, or thinking about really getting into anatomy). So, in the interest of saving everyone a lot of time and effort, it would be great if the folks that know from sitting on a fence rail that the horse’s hock is the problem would also opine as to whether it’s the tibiotarsal joint, the proximal intertarsal joint, the distal intertarsal joint, of the tarsometatarsal joint that’s causing the problem.

SECOND ASIDE: Probabilities aside, when people say, “Let’s do hock injections,” my immediate thought is, “Which joint?” The horse’s hock isn’t a single joint. The hock is made up of 10 bones and four major joints (you can look the names up if you’re really into anatomy, or thinking about really getting into anatomy). So, in the interest of saving everyone a lot of time and effort, it would be great if the folks that know from sitting on a fence rail that the horse’s hock is the problem would also opine as to whether it’s the tibiotarsal joint, the proximal intertarsal joint, the distal intertarsal joint, of the tarsometatarsal joint that’s causing the problem.

But I digress.

From a veterinary perspective, the way that a concern about a horse’s lack of performance or possible lameness should be handled is this.

- An owner/agent is concerned that a horse might have a problem.

- That person calls their veterinarian.

- The owner/agent is open to the idea that the problem might not be the hock – might not even be a physical problem – and particularly if the exam shows that there is something else going on.

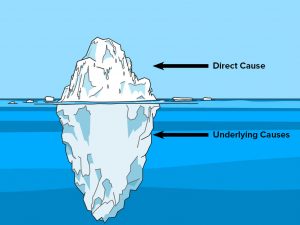

THIRD ASIDE: One of the things that puzzles me is why people are always assuming that there’s always some sort of a medical underlying problem for the horse not being willing to respond in the way that the people want it to respond. I mean, sure, a horse could have a hock problem. He might also have a bit problem. He might also not be responding due to something the rider is doing.  He might also be bored out of his mind because he’s being asked to do the same thing day after day after day (after day). Not every problem has a medical solution. And – here’s a news flash – if you can eliminate the underlying cause, the problem usually goes away.

He might also be bored out of his mind because he’s being asked to do the same thing day after day after day (after day). Not every problem has a medical solution. And – here’s a news flash – if you can eliminate the underlying cause, the problem usually goes away.

- The veterinarian does a thorough examination.

- A treatment plan is devised.

Unfortunately, this sequence sometimes doesn’t happen. In fact, the system can – and often does – break down.

REASONS TO CONSIDER INJECTING YOUR HORSE’S HOCK(S)

There are usually one of two reasons you might consider injecting your horse’s hocks.

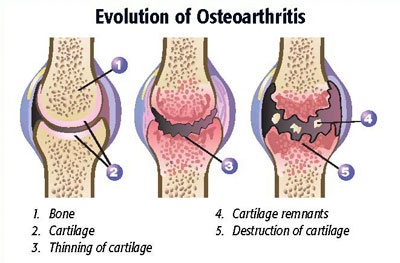

- He’s got a chronic problem. Specifically, he has osteoarthritis. A lot of people call this “bone spavin.”

ETYMOLOGY! For those of you that love studying word origins as much as I do, the word “spavin” comes to us from old French, from a verb meaning “to hop like a sparrow.” This tells you both that the Old French were pretty keen observers and that horses were really important to them, too.

ETYMOLOGY! For those of you that love studying word origins as much as I do, the word “spavin” comes to us from old French, from a verb meaning “to hop like a sparrow.” This tells you both that the Old French were pretty keen observers and that horses were really important to them, too.

If your horse has osteoarthritis, the joint isn’t not healthy. The cartilage is wearing away. There’s a lot of inflammation. The joint hurts. Medication can be injected to help relieve the pain and inflammation, at least temporarily, at least sometimes. The most commonly injected drugs shot into horses’ hocks are one of several corticosteroids, although there a number of other injectable experimental alternatives that suffer from a lack of good evidence that put into horse joints with plenty of regularity (PRP, stem cells, and many others). Of course, there are many other additional treatments, that can be recommended along with injections. In particular, orally administered pain-relieving medications do help control pain and inflammation in many horses and are commonly recommended. In addition, there are myriad supplements all of which have been said by the manufacturer to be amazingly effective at “supporting” your horse’s joints (Go, Your Horse’s Joints!!!).

THIRD ASIDE: In general, don’t believe everything that you read, and particularly when it comes to horse joint supplements.

- His joint is inflamed. This is also arthritis (joint inflammation), but, unlike osteoarthritis, which involves the bone, with simple arthtritis it’s not all doom and gloom. It is possible for a horse’s joint to be sore and for there also NOT to be a serious problem. Come to think of it, it’s also possible for a horse’s joint to get sore and for it NOT to develop into a serious problem.

Overdoing it for a sprained ankle

Think of a person who sprains an ankle. With rest and rehab – and possibly a little medication – things get better. You step off a curb. You twist your ankle. Your ankle is tender. Do you go to the doctor and ask for ankle injections? After a sprained ankle, people also usually don’t have long term health problems. They usually don’t develop osteoarthritis of the ankle, either. Horses are like that, too. But sometimes a little bit of anti-inflammatory medication can calm things down. Oh, and tincture of time. That always helps a lot. Joint injections can help calm down inflammation, too, but the question then is along the lines of, “Why would you use a fire hose when all you need to do it put out a match?”

BUT WHAT ABOUT HOCK INJECTIONS?

“Hey doc, how about some knee injections!”

Right. If your horse has an inflamed hock – if it’s been demonstrated that your horse has a problem in one of the hock joints – injecting the hocks may be a reasonable option.

FOURTH ASIDE: To me – and I realize my opinion is apparently not shared by everyone – this demonstrating that there’s a problem before treating the horse as if there is a problem is important. Imagine if you went to your doctor and said, “I’d like to have my knees injected.” Would you expect your doctor to just fill up a syringe and inject away?

That said, joint injections certainly can help relieve joint pain and inflammation. However, I think that there are several big reasons why so many horses get their hocks (or other joints) injected:

- People aren’t patient. Whereas you (and probably your horse) might be more than happy to wait for your ankle to feel better – take a couple of ibuprofen, take it easy, and let things get better – your horse might have an important competition coming up this week (or every week) and you want to see if you can put some sort of a pharmacological band-aid on him.

People have been convinced that joints need “maintenance.” I’ve written about that (CLICK HERE TO READ THE ARTICLE). I suppose that, in some way horses do need “maintenance, particularly if you broadly define maintenance as “good care.” But the idea that horses need periodic injections into the hocks so that their joints will work better – so that they can jump, run, spin, etc. – is just ridiculous. It’s expensive, too.

People have been convinced that joints need “maintenance.” I’ve written about that (CLICK HERE TO READ THE ARTICLE). I suppose that, in some way horses do need “maintenance, particularly if you broadly define maintenance as “good care.” But the idea that horses need periodic injections into the hocks so that their joints will work better – so that they can jump, run, spin, etc. – is just ridiculous. It’s expensive, too.- The hocks are easier to inject that just about anywhere else on the horse’s hind end. This may come as news to some folks, but horses are not generally keen to have sharp objects poked into their back legs. If the horse can be injected and the injector can more easily avoid getting a hoof planted into his or her face, more’s the better. Plus, the injector looks like a real expert (it’s a prestige thing).

- Injecting the hock joints doesn’t just affect the hocks. Otherwise stated, when you flood a horse’s joints with the corticosteroid medications commonly used, the medication doesn’t stay in the joints. In fact, it goes all through the horse’s system, where it can have all sorts of effects. For example, in 2020, it was shown that horses with asthma got better after having had their hock joints injected (CLICK HERE). Plus, steroids make horses feel better in general. Otherwise stated, even if your horse is normal, if you inject his hocks, he may feel good, at least for a time.

HOW LONG DO HOCK INJECTIONS LAST?

To my knowledge, there’s been only one study that specifically looked at the question of how long hock injections last. And the answer is… about two months, on average. CLICK HERE to read my article about that.

A COUPLE OF DUMB IDEAS

For some reason, there seems to be this idea that if you inject one hock (or coffin joint, or any other joint) it’s somehow mandatory to inject the other one. That’s why people often talk about a horse’s “Hocks need to be done.” Maybe a horse has problems in more than one joint. However, if the problem is only in one joint, then why not inject only one joint? It’s sort of like going to the doctor and saying, “I know I sprained my left ankle, but as long as I’m here, can you treat the right one, too?” In case you were worried, injected one joint doesn’t “unbalance” the other, either (I have no idea where this thought came from).

For some reason, there seems to be this idea that if you inject one hock (or coffin joint, or any other joint) it’s somehow mandatory to inject the other one. That’s why people often talk about a horse’s “Hocks need to be done.” Maybe a horse has problems in more than one joint. However, if the problem is only in one joint, then why not inject only one joint? It’s sort of like going to the doctor and saying, “I know I sprained my left ankle, but as long as I’m here, can you treat the right one, too?” In case you were worried, injected one joint doesn’t “unbalance” the other, either (I have no idea where this thought came from).

There’s also this idea that once you start injecting a horse’s hocks, you’re always going to have to be injecting a horse’s hocks (or other joints). That one baffles me, too. A healthy joint should NEVER need injecting. If it seems like recommendations are being made that a horse’s joints get injected with regularity, there’s got to be some sort of problem. Figuring out what that problem is a much better solution that just filling another syringe and injecting away.

MAYBE THERE’S A BETTER WAY?

Personally, I think that there are a lot better ways to handle horses – particularly competition horses – than injecting them in the hocks (and other joints) with regularity. Here are some other possibilities.

Personally, I think that there are a lot better ways to handle horses – particularly competition horses – than injecting them in the hocks (and other joints) with regularity. Here are some other possibilities.

- Consider changing things up for horses so that they’re not doing the same thing every day. This helps avoid problems with repetitive stress injuries. It helps keep horses from getting bored, too. Maybe the training regimen could be tweaked, or the frequency of stressful riding could be reduced, or the intensity of the riding could be modified. Maybe the rider could ride better. I mean, if the horse and rider are a team, why should the blame always be places on the four-legged member?

FIFTH ASIDE: In my career, I have met two – two – rider/trainers who, when their horse isn’t going well, always first assume that they are the problem. Both of them have been very successful.

- Let them move as much as possible.

- Rest and rehab go a long way to helping horses get better from a lot of problems, even without injections.

- Maybe the horse does have a chronic problem like osteoarthritis. Maybe you can reduce expectations and you can both live with the problem.

BOTTOM LINE?

It’s complicated. And, as one of my favorite quotes, by the Baltimore Sun columnist H.L. Mencken goes, “For every complex problem, there’s a solution that’s simple, easy, and wrong.” If your horse isn’t performing to your expectations, if there’s a problem with your horse, or a some problem keeps happening, the ideal thing to do is to try to get to the root of the problem. Don’t just keep sticking needles into his hocks.

It’s complicated. And, as one of my favorite quotes, by the Baltimore Sun columnist H.L. Mencken goes, “For every complex problem, there’s a solution that’s simple, easy, and wrong.” If your horse isn’t performing to your expectations, if there’s a problem with your horse, or a some problem keeps happening, the ideal thing to do is to try to get to the root of the problem. Don’t just keep sticking needles into his hocks.