I wish that discussions about vaccines were easy. It would be great to have this sort of vaccine equation:

I wish that discussions about vaccines were easy. It would be great to have this sort of vaccine equation:

Horse + vaccine + (reactions x 0) = no disease

Otherwise stated, you give a horse a vaccine, he doesn’t have a reaction, and it prevents the disease he’s being vaccinated against.

Simple. But life it’s simple. The vaccine looks more along the lines of this:

Horse + vaccine (+/- effectiveness) + (reactions +/-) = no disease (+/)

Horse + vaccine (+/- effectiveness) + (reactions +/-) = no disease (+/)

The actually equation has a lot of +/- variables in it, which makes discussions about vaccines fraught with all sorts of nuance and complications. Nuance and complications, or course, make everyone throw up their hands, so, rather than talk about them, vaccination discussions often devolve into things like, “All vaccines are bad, so if you vaccinate your horse, you must not care about him” or, alternatively, “If you don’t vaccinate your horse, you must not care about him.”

Let’s not go there.

Instead, let’s talk about what would, on it’s face, seem to be a reasonable alternative to vaccination for some horses. But first, a quick review of how vaccines (are supposed to) work.

Instead, let’s talk about what would, on it’s face, seem to be a reasonable alternative to vaccination for some horses. But first, a quick review of how vaccines (are supposed to) work.

- You give the vaccine against a disease

- The vaccine produces antibodies against that disease (antibodies, if you don’t already know, are immune factors that are circulating around in the horse’s blood)

- The horse gets exposed to the disease

- The antibodies fight off the disease (or cells that make antibodies get revved up when they are exposed the disease)

- The horse doesn’t get sick from the disease

Antibodies are the key thing here. They’re “key” in two ways. The first, and most obvious, is that antibodies are very important disease fighters. The second, at least insofar as people who study immune systems go, is that antibodies can be measured. The ability to measure antibodies allows scientists to engage in scientific activities, which is one of the most fun things that scientists like to do, at least when they are at work. The word that described measuring antibody levels in the blood is, “Titer.”

It is not at all irrational to think, “Well, if my horse’s antibody levels – titers – are high enough, he won’t get the disease that I’m worried about, and I won’t need to vaccinate him. If I don’t vaccinate him, he won’t have a vaccine reaction. Everybody wins!” In fact, some people do think like that. Some people advise some people to think like that. That’s what this article is about, cupcake.

It is not at all irrational to think, “Well, if my horse’s antibody levels – titers – are high enough, he won’t get the disease that I’m worried about, and I won’t need to vaccinate him. If I don’t vaccinate him, he won’t have a vaccine reaction. Everybody wins!” In fact, some people do think like that. Some people advise some people to think like that. That’s what this article is about, cupcake.

The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) just posted (on October 26, 2020) their “AAEP Guidelines for Serology in Horses with Adverse Events from Vaccination.” You can dig through them is you like by CLICKING HERE. The Guidelines are 20 pages long, with references and a disclaimer, so, in case you have something else that you want to do besides digging through them, I thought I’d go through them for you. The Guidelines have their own headings, so we’ll use those. Hopefully, it helps.

INTRODUCTION

First, these guidelines are not directives. That is, they’re not trying to tell anyone how to practice medicine (even if, maybe they should). Nevertheless, they start out by pointing out the the horse’s immune system is complicated.

First, these guidelines are not directives. That is, they’re not trying to tell anyone how to practice medicine (even if, maybe they should). Nevertheless, they start out by pointing out the the horse’s immune system is complicated.

ASIDE: The fact that the immune system is complicated is something to keep in mind when someone tells you about this or that “immune boosting” product. Without some sort of specific, measurable response, the whole idea is just silly. If you want to boost your horse’s immune system, I propose this cheer: “Antibodies, antigens, white cells too, B-Cells, T-Cells we love you!” It will be just as effective and it won’t cost you anything.

Next, they point out that an antibody response and protection hasn’t been established.

ANOTHER ASIDE: When you think about it, you could just stop right there.

savagechickens.com

Next, they throw the responsibility for determining whether to use titers on the shoulders of individual veterinarians, which, honestly, is kind of pointless, in my opinion. I mean, for obvious reasons, a panel of top experts in the field is probably in a better position to draw conclusions that is an individual veterinarian. However, no one wants to step on any toes, so on we go.

Next, vaccine side effects are mentioned. If somebody’s horse has a bad reaction to a vaccine, it’s completely rational to want to avoid vaccination. You can certainly do that (with certain exceptions, especially rabies). Unfortunately, you can’t also avoid vaccination and at the same time be assured that your horse is protected from disease by doing a blood test. It’s a great idea – it doesn’t work.

IMMUNOLOGY CONSIDERATIONS

IMMUNOLOGY CONSIDERATIONS

It’s complicated.

VACCINE TYPES AND IMMUNE RESPONSES

There are different kinds of vaccines, some work better than others, and on different things.

Next, the guidelines move to specific diseases.

Close-up of a disease causing agent in the horse

Eastern/Western Equine Encephalomyelitis (EEE/WEE)

Antibodies are probably pretty important in fighting the disease. However, you can’t know for sure if a certain titer is protective.

YET ANOTHER ASIDE: Since the diseases are fatal, and, in the case of EEE, humans can get it, too, I’d be a little worried about relying on titers in this situation if it was my horse.

Rabies

This is a bad disease that can be prevented by annual vaccination. Like EEE, people can get rabies from a horse. Plus, many states have vaccine requirements that you have to follow or you’re breaking the law. If your horse isn’t in an endemic area, he probably doesn’t need to get vaccinated (which is the same as with every other disease). Titers probably do correlate with protection but then again, it’s always a good idea to follow the law.

Tetanus

Here’s another bad disease that can be prevented by vaccination. There have been a number of studies on different vaccines. Titers might help if you don’t want to vaccinate against tetanus, and titers probably indicate protection. Then again, if your horse were to get tetanus, the odds of a successful treatment outcome are not in your horse’s favor.

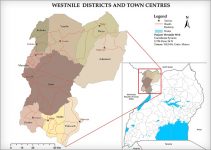

Where West Nile started (Uganda)

West Nile Virus

Were not sure what titers mean. This disease also kills horses, but it’s not as big a killer as other diseases. Vaccines seem to be pretty effective.

Equine Influenza

If you shoot flu vaccines up your horse’s nose, you’re not going to see an increase in titers like you will if you give it in the muscle. If your horse has reactions to the muscle shot, squirt an approved vaccine up his nose.

Yes, another aside: Vaccination intervals for influenza (and herpesvirus, too) may be out of your hands if you show horses. Show organizations have their own rules. They really don’t have much relationship to scientific guidelines.

Herpesvirus 1 or 4, I’m not sure

Equine Herpesvirus (1 and 4)

Even if you measure antibody levels, antibodies in the blood don’t protect against the disease anyway. Don’t bother doing serology on horses for this disease.

Strangles (Streptococcus equi subspecies equi)

You can’t tell if a horse is protected with titers. On the other hand, if your horse has high titers, it may not be a good idea to vaccinate him.

LAST ASIDE, I PROMISE. I don’t recommend that my clients use strangles vaccines because, for one reason, there’s no good evidence that they work anyway. I have cost myself a lot of money with this recommendation.

SUMMARY

SUMMARY

I’m just going to quote the Guidelines. “Levels of circulating tetanus toxin binding antibody and rabies virus neutralizing antibody appear to correlate with protection in the horse. For most other vaccine antigens,the correlation between vaccine-induced serologic response and protection has either not been established or is not plausible based on the biology of the disease in question.”

So there. Hope this helps!