You want to protect your horse against infectious diseases, of course. In that regard, vaccination has proved to be one of the most successful means of preventing disease ever discovered. Period. But every time you get your horse his shots, he gets sick, and sometimes alarmingly so. You don’t want him to get sick, and, well, you don’t want him to get sick. So, what do you do?

You want to protect your horse against infectious diseases, of course. In that regard, vaccination has proved to be one of the most successful means of preventing disease ever discovered. Period. But every time you get your horse his shots, he gets sick, and sometimes alarmingly so. You don’t want him to get sick, and, well, you don’t want him to get sick. So, what do you do?

I’ve been vaccinating horses for over 3 decades. Here are the problems that I’ve sometimes – rarely – seen:

- Soreness and/or swelling at the injection site

- Fever and./or loss of appetitie

- Injection site abscesses

- Limb swelling

I’m aware of stories of other, more serious reactions, such as laminitis, or systemic shock. I just haven’t seen them (which is one reason why you can’t rely on your own personal experience as the determinant of everything – I don’t doubt that they can happen, it’s just that I haven’t seen them). And, when really bad reactions do occur, they’re terrible, no doubt.

So, how often have I seen vaccine reactions? Well, to be honest, almost never. It’s also my impression that I’m seeing vaccine reactions less frequently every years, which I guess is because of improvements in vaccine technology. I don’t know that, but I do know that vaccine technology has changed, and I’m seeing fewer and fewer problems every year.

So, if that’s my experience, how about a more broad-based, maybe industry-wide experience? That’s where it gets a bit annoying. The fact is that veterinarians don’t really have a firm grasp on the extent of the problem. And the reason for that is pretty simple: nobody is really keeping good track.

So, if that’s my experience, how about a more broad-based, maybe industry-wide experience? That’s where it gets a bit annoying. The fact is that veterinarians don’t really have a firm grasp on the extent of the problem. And the reason for that is pretty simple: nobody is really keeping good track.

Right now, the only way that the companies who produce vaccines know if a horse has had a reaction is if someone calls in to report a problem, and, frankly, not everyone does that. Most commonly, the people who are calling in are veterinarians, and when they call, the companies do keep track, but they don’t tell anyone about the data, because, well, currently they don’t have to tell anyone. But you can still get some idea of the safety of vaccines from clinical safety trials that are performed before the vaccines can be released. For example, for one company’s influenza vaccine, a total of over 700 horses received a total of more 1400 doses, and they reported no severe systemic reactions, and swelling at the injection site in 2% of the horses.

But like I said, nobody is keeping track. all of the major vaccine companies keep these sorts records, but the United States Food and Drug Association doesn’t currently receive the data. Happily, this appears to be about to change, that is, the FDA will be getting data within the next couple of years. Right now, though, I think it’s safe to say that vaccine reactions are an uncommon, but that they are still troubling problem for some horses, and, of course, horse owners, by proxy.

So let’s say that you’re one of those unfortunate owners with one of those unfortunate horses. It kind of puts you between a rock and a hard place to a certain extent. On the one hand, you want to protect your horse against diseases that will make him really sick – or worse – but on the other hand, you don’t want him to get really sick from the vaccine. So, what do you do? Here are some suggestions, based mostly on my clinical experience, and in no particular order.

1. Change brands. I have no idea what’s in each and every vaccine that’s made for horses, but it does seem to me that some of them are more likely than others to cause reactions in individual horses. So, if your horse reacted to his shots, make sure you call your veterinarian (as well as the USDA – more on that in a bit) and ask him what brand he or she used, and ask not to have that brand used next time. Of course, you should keep track, too – nobody should mind a little boost in the memory department.

1. Change brands. I have no idea what’s in each and every vaccine that’s made for horses, but it does seem to me that some of them are more likely than others to cause reactions in individual horses. So, if your horse reacted to his shots, make sure you call your veterinarian (as well as the USDA – more on that in a bit) and ask him what brand he or she used, and ask not to have that brand used next time. Of course, you should keep track, too – nobody should mind a little boost in the memory department.

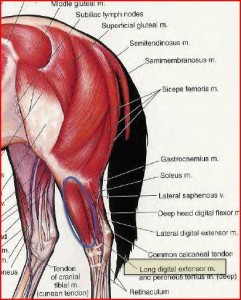

2. Change sites. Most horses get vaccinated in the neck muscles. That’s mostly because the neck muscles are right there in front of you, and a long way from kicking hind legs. However, when compared to other areas of the horse’s body (hint: hind legs), there’s not as much muscle in the neck, and the muscles are a lot smaller. So, some horses may do better if the vaccine is given in the hind limbs.

NOTE: Hind limbs means lower on the leg, not up on the hip. While there’s plenty of muscle on the horse’s hip, if a horse gets an abscess/infection from a hip muscle injection, it can be harder to deal with. Use the big muscles lower in the hind limb (the semi-membranosus and semi-tendinosus, for you anatomy freaks).

NOTE: Hind limbs means lower on the leg, not up on the hip. While there’s plenty of muscle on the horse’s hip, if a horse gets an abscess/infection from a hip muscle injection, it can be harder to deal with. Use the big muscles lower in the hind limb (the semi-membranosus and semi-tendinosus, for you anatomy freaks).

3. Change route of administration. A couple of vaccines can be given by the intra-nasal route of administration. There’s a vaccine against strangles – which, for a number of reasons, I do not recommend for my clients – and there’s also a vaccine against equine influenza virus (EIV) and equine herpesvirus (EHV-1 and EHV-4) that can be squirted up the horse’s nose. As you might imagine, many horses usually aren’t particularly enthusiastic about having stuff squirted up their noses, but that’s another problem, and it’s usually one that can be dealt with. Still, for some diseases, when available, the intra-nasal (IN) route of administration can offer a very viable, albeit somewhat annoying (especially for the horse), alternative.

4. Exercise post-vaccination. Not you. Your horse. Pretty much as soon as your horse has received a vaccination, get him out and get him moving. Go for a ride. Lunge him. Turn him out and chase him. Get him moving. When you put a vaccine into a horse, it sits in the muscle for a bit. With exercise, the idea is to get the vaccine outta there. Exercise gets the blood pumping, blood circulates rapidly through the muscle (up to 30 times more quickly than in a resting horse), and the vaccine gets moved from the muscle. At least that’s the theory, and it’s something that I’ve done.

CURIOUS ASIDE: Ever since I can remember, it’s been advised to give horses a day off after their vaccines. I’m not sure where this recommendation comes from, but I can think of a few reasons why that might be given as advice.

- If your horse does have a mild reaction, and you give him a day off, and you stay away from the barn, you’ll be less likely to have a nervous breakdown

- If you don’t have a nervous breakdown, your veterinarian will be less likely to get a frantic phone call

- Trainers need a day off, too

Anyway, as I said, I quite commonly recommend that people exercise their horses after vaccination, and it seems to help. Might work for your horse, too.

5. Vaccinate against only one disease at a time. I know of some people that vaccinate their horses one disease at a time, so as to try to prevent them from getting the horse’s immune system “overloaded.” I understand the sentiment, but, given that the horse is exposed to literally thousands of immune system stimuli every day, worrying about whether you give him 1 more or 6 more at a time doesn’t seem like it would make a lot of difference. And, of course, then you have to give your horse vaccinations every month or so, if you want to cover against the most common diseases. I’m not saying that it’s not worth the effort, just that trying to split out each individual vaccine is a considerable effort. Interestingly, there’s some evidence that separating vaccines increases the immune response to each vaccine, compared to the vaccines with lots of things in them (e.g., “Four-Way”) but I don’t know if it’s a big enough difference to make a difference.

6. Give him an anti-inflammatory medication. I have at least one client that asks me to give an injection of an anti-inflammatory medication at the same time that I give the vaccination, and the horse apparently doesn’t have reactions. It’s certainly a harmless enough practice, and it might be worth a try.

7. Vaccinate your horse only against things that he really needs to be vaccinated against. I’d certainly advise you working with your veterinarian to find out what vaccines your horse(s) really needs. For example, I don’t advise that my clients use any of the current vaccines against strangles because, 1) They have a reputation for causing vaccine reactions, 2) There’s essentially no good evidence that they actually prevent strangles, and 3) Some horses have gotten strangles from the intranasal vaccine. Rabies isn’t prevalent in my practice area, so I rarely vaccinate horses against it. Ditto botulism – an effective vaccine, but it’s not something that we concern ourselves with much in southern California. Or African Horse Sickness… well, I’m sure you get the point. Like I said, work with your veterinarian on this. He or she knows what’s best in the part of the world where you live.

7. Vaccinate your horse only against things that he really needs to be vaccinated against. I’d certainly advise you working with your veterinarian to find out what vaccines your horse(s) really needs. For example, I don’t advise that my clients use any of the current vaccines against strangles because, 1) They have a reputation for causing vaccine reactions, 2) There’s essentially no good evidence that they actually prevent strangles, and 3) Some horses have gotten strangles from the intranasal vaccine. Rabies isn’t prevalent in my practice area, so I rarely vaccinate horses against it. Ditto botulism – an effective vaccine, but it’s not something that we concern ourselves with much in southern California. Or African Horse Sickness… well, I’m sure you get the point. Like I said, work with your veterinarian on this. He or she knows what’s best in the part of the world where you live.

WHAT NOT TO DO ABOUT VACCINE REACTIONS

I wouldn’t recommend avoiding vaccinations for your horse altogether, except in the most extenuating circumstances. That’s because there are diseases that horses can get that are caused by agents in their environment. Diseases like tetanus, encephalitis, and West Nile virus don’t require your horse to be around other horses in order to contract them. It’s a risk benefit thing – the risk of being vulnerable to disease vs. the risk of adverse vaccine reactions. Of course, you can mitigate that to a certain extent, for example, if your horse rarely sees other horses, the risk of getting a communicable disease, such as the flu, is pretty small. Trying to come up with the best risk:benefit strategy for your horse is something that you should work out with your veterinarian.

I’m also not a fan of running vaccine titers. The idea behind running titers is seductively simple: if you can measure a titer, it must mean that your horse is protected from that disease. Unfortunately, we don’t know if that’s true, that is, nobody really knows what level of titer is protective against which disease. So, to a certain extent, when you pay to run titers, you’re just paying for a false sense of security (and you’re probably paying more than if you just vaccinated). I’m not a big fan of that approach.

Oh, and one more thing. If your horse has had an adverse reaction to a vaccine, please get your veterinarians to report it. Take a look at the recommendations of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) – you can see their complete report if you CLICK HERE.

BOTTOM LINE: There’s just no way to completely avoid vaccine reactions for every horse, every time. Fortunately, vaccine technology has made reactions much fewer than in years past, at least in my experience. Ask your veterinarian what his or her recommendations are, and, if you want a second opinion, follow up with a call to a local or regional veterinary college, and ask to speak to a medicine specialist there. Your horse deserves your attention. And, of course, if your horse does have a reaction, get in touch with your veterinarian, so that they can help him (and you) through the problem.

BOTTOM LINE: There’s just no way to completely avoid vaccine reactions for every horse, every time. Fortunately, vaccine technology has made reactions much fewer than in years past, at least in my experience. Ask your veterinarian what his or her recommendations are, and, if you want a second opinion, follow up with a call to a local or regional veterinary college, and ask to speak to a medicine specialist there. Your horse deserves your attention. And, of course, if your horse does have a reaction, get in touch with your veterinarian, so that they can help him (and you) through the problem.

There’s no guarantee that your horse is never going to have an adverse reaction to any vaccine. But the chances are, he won’t. And, chances are, if he does, it won’t be a big deal. But if he does have a reaction to one vaccine, there are things that you can do to try to prevent future reactions. Most importantly, talk to your veterinarian, and, if need be, talk to other veterinarians, too, in order to come up with the best plan for your horse.